Key Points:

- Charles Labofish emigrated to the US from the Russian Empire in 1888 and held 15 US, Canada and British patents for his inventions, six of them being calculating machines.

- He also owned patents for typewriters, cyclometers, a log-sawing machine, and an indicating device for bicycles.

- Charles Labofish authored a book titled Labofish’s Catechism of Patents and Inventions, How Made.

Charles Labofish

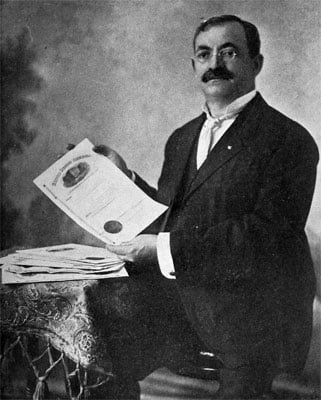

In the late 19th and early 20th century Charles Schachan Labofish, a Jewish immigrant from Odessa, Russian Empire, who came to America in 1888 (see biography of Charles Labofish), devised various machines (calculating machines, typewriters, log-sawing machine, cyclometers, indicating device for bicycles, etc.) and received some 15 US, Canada and Great Britain patents for his devices, six of them for calculating machines (US533361, US544360, US661058, US673877, CA51938, and GB190101736).

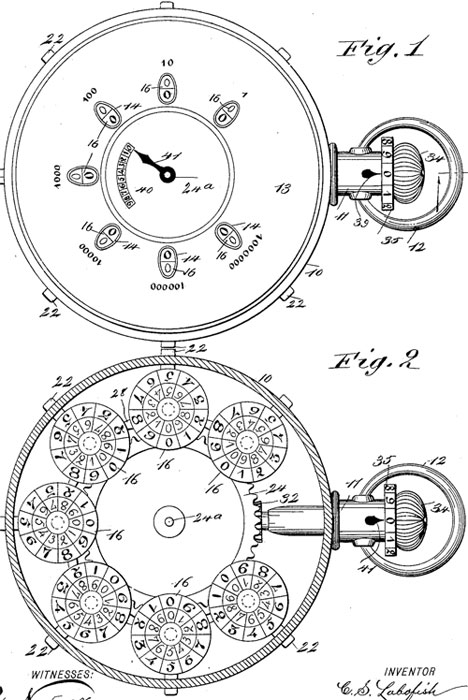

The first two patents for calculating machines of Labofish are describing a watch-like adding machine (see the lower patent drawing). Let’s examine the device, using the patent drawing of US533361

The object of Labofish’s invention is to produce a very simple and efficient calculating machine, which may be made in the form of a watch and conveniently carried in the pocket, which operates without keys, which is not likely to get out of order or make mistakes, and which may be easily operated to perform the various operations in addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

The device has several number wheels (marked with 16 in the drawing), each number wheel having on its face concentric rows of figures from 0 to 9, the rows being arranged in reverse order, with their 0’s on the same radial line as shown clearly in Fig. 2, and the rows of figures on each wheel are dissimilar, preferably both in style and color, so that one row may be readily distinguished from the other. The object of this reverse arrangement is to enable one row of numbers to be used in addition and multiplication, and the other row to be used in subtraction and division. The number wheels are arranged to represent units, tens, hundreds, etc., as in Fig. 1 are shown seven of them, but any necessary number of wheels may be used.

In order to provide for carrying “one” in working the machine, it is necessary to have means for turning one wheel a distance of one number at each rotation of the adjacent wheel representing a lower denomination, and to this end, each barrel 17 has on one side a projecting stud or tooth 26, which is adapted to engage the notched or forked end 27 of a lever 28, which is pivoted on the base 19 just below the pinion 23, and the lever projects over the next adjacent base and is provided with a pivoted pawl 29, which is adapted to engage the pinion of the next number wheel, the lever and its pawl being held in engagement with the stud and the pinion by springs 30 and 31.

The machine is operated by turning the crown head 34 to the right, according to the numbers to be added, multiplied, subtracted, or divided. In operating the machine, the number wheels to be moved are pressed inward by pushing one of the push buttons 22, thus throwing its pinion 23 into gear with the driving gear 24, and then, by turning the crown head 34, while the pinion is held in gear with the gear wheel the appropriate number wheel is rotated.

Let’s suppose, for instance, that the number 341 is to be added to the number already indicated on the face of the machine. The push button 22 opposite the units slot is pushed inward, thus throwing the units pinion 23 into engagement with the gear wheel 24, and the crown head 34 is pushed inward slightly and turned to the right a distance of one number, thereby turning the units wheel a corresponding distance by means of the gear connection described, and if the number 5, for instance, has been previously shown in the said slot over the units number wheel, the number 6 will now appear and, after this, the pressure on the push button is removed and the crown head pulled out slightly so as to release it from the spring detent 38 and permit it to return to its normal position. The push button of the tens wheels is then pushed in, thus throwing the tens number wheel into gear and the crown head is then turned a distance of four numbers, thus moving the tens number wheel a corresponding distance and adding 4 to the amount already shown in the tens sight slot. The operation is then repeated on the hundreds number wheel, this being turned a distance of three numbers and the sum is then registered and exhibited in the sight slots. It the sum of any two numbers exceeds ten, the tooth 26 of the number wheel, being operated, is brought into engagement with the lever 27 which is tilted and turns the next number wheel of a higher denomination one notch or number. The sums, in addition, are exhibited by the inner row of figures in the sight slots, and if subtraction or division is performed, the result is shown by the outer row of figures.

In subtracting, the operation is exactly as in adding, except that reference is made to the outer row of figures in the sight slot, and if the crown head is turned to the right the outer row of numbers diminish at the same rate that the inner row increase. If then the number 341 is to be subtracted from the number already shown on the dial of the machine, the same steps are taken as above described, but in the units, tens, and hundreds sight slots numbers will appear which are 1, 4, and 3 respectively, less than the numbers previously shown.

As multiplication is successive additions and division successive subtraction, it will be readily seen that these operations may be performed by simply turning the crown head in a manner to repeat the additions or subtractions.

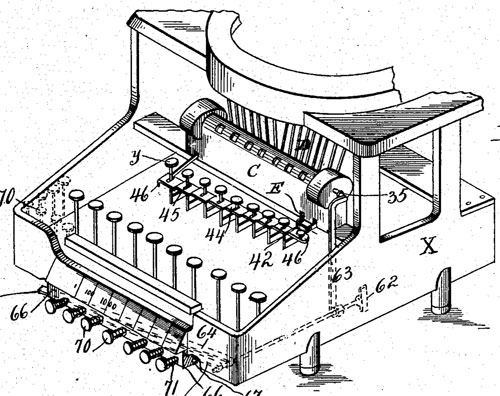

The next two patents of Labofish are describing calculating devices for typewriters (see the lower patent drawing).

The object of the invention is to simplify the means used for calculating purposes and to provide sure means of extending the usefulness of such devices by constructing the same so compact and of such a nature and so entirely automatic as to make its application to a typewriting machine perfectly practical so that the mere writing of a column of figures on the typewriter will simultaneously register and add the said column of figures within the device automatically without encumbering the typewriter in the least.

Charles Labofish as an Author

Besides owning multiple patents, Charles Labofish was an expert on the subject of obtaining patents in his day. He authored the book Labofish’s Catechism of Patents and Inventions, How Made: A Veritable School of Self-Instruction in Patents and Inventions, With Questions for Self-Examination, which is available through the Classic Reprint Series published by Forgotten Books. An excerpt from the book is shared below, which will give you an idea of the subject matter:

“Years of incessant application, azssidnons, deep and reflective meditation, and practical experience with patents and inventions, delving into the very root of the art, science and practice of patents and inventions, yearning for a ray of success, led the author of this work to the conclusion that success with patents is concurrent with the amount of knowledge of the underlying legal and commer cial principles governing patents and inventions possessed by the inventor. An inventor having little or no knowledge of the spirit of our patent laws,’depending entirely upon his patent attorney for. The proper preparation and prosecution of his application before the Patent Office, does not gener ally get the p-atent he IS entitled to; hence, a fails.ure. An inventor devoid of a thorough knowledge of the laws of patentability of invention and discova ery is often the sole owner of a worthless patent; hence a dire failure. An inventor devoid of a prac tical working knowledge Of science and mechanics produces crude and impractical inventions; hence, a commercial failure. An inventor lacking in an understanding of the principles governing patents and inventions is readily attracted by the flaring advertisements of professional p cm 15 e t-m a k e r s and becomes the sole owner of a guaranteed patent for the full term of seventeen years; hence, a long, asting and humiliating failure.“

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Unknown author / public domain