Eduard Selling

In 1886 the professor of mathematics at the University of Würzburg, Germany, Eduard Selling (1834-1920) (see biography of Selling) received a patent for a calculating machine with very interesting construction.

Since 1877 Selling had been commissioned by various ministries dealing with actuarial matters, especially on the revision of the pension system in Bavaria. For his extensive mathematical calculations, he used a calculating machine of Thomas de Colmar, which he criticized because of some deficiencies. That’s why, he decided to create his own altogether different multiplication machine, which was to be offered at a lower price and to avoid all drawbacks of Thomas’ machine.

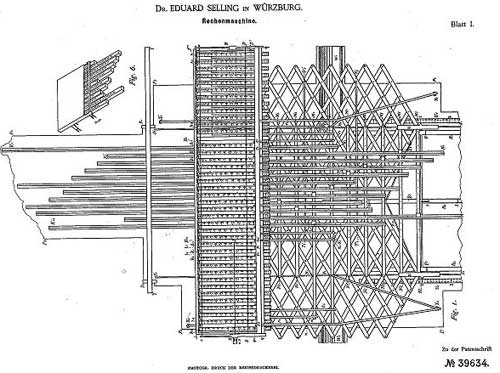

The first variant of the device was patented in 1886 (Deutsches Reichs-Patent №39634, 16th of April, 1886), later on Selling received 3 more patents in Germany for improvement of his machine, as well as 1 patent in Austria, 1 in Belgium, 1 in Switzerland, 1 in France, 2 in England, 1 in Italy and 1 in the USA.

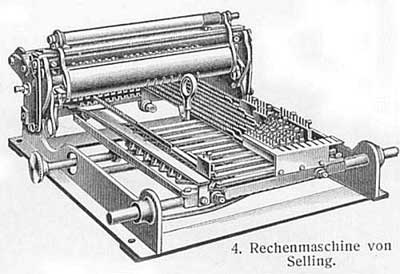

The machine (see the photo below) was put into production, although in small quantities (some 30-40 machines were produced until the production ended in 1898), by the Workshop for Precision Mechanics of Max Ott, in Munich. The price was 400 marks. The calculating machine of Selling was awarded at the Chicago World Fair in 1893.

The teenager son of a friend of Selling, the future genius of mechanic calculating machines, Christel Hamann, took part in the construction of the machine

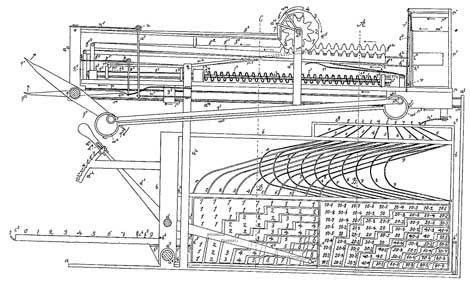

The internal mechanism of the machine is based on the so-called Nürnberger Schere (a popular toy of this time), in English this mechanism is called Nuremberg scissors or lazy-tongs (see the patent drawing below).

The machine is 35 cm wide, 40 cm long and 15 cm high.

The calculating wheels of a regular calculating machine (which transfers the motion to the digital wheels) are replaced by lazy tongs. To the joints of these the ends of racks are pinned, and as they are stretched out the racks are moved forward 0 to 9 steps, according to the joints they are pinned to. The racks gear directly in the digital wheels and the figures are placed on cylinders. The carrying is done continuously by a train of epicycloidal wheels. The working is thus rendered very smooth, without the jerks which the ordinary carrying tooth produces; but the arrangement has the disadvantage that the resulting figures do not appear in a straight line, a figure followed by a 5, for instance, being already carried half a step forward. This is not a serious matter in the hands of a mathematician or an operator using the machine constantly, but it is serious for casual work. Anyhow, it has prevented the machine from being a commercial success. Actually, this was the second machine with continuous tens carry, after the calculating machine of Chebyshev. For ease and rapidity of working it surpasses all other machines. Since the lazy tongs allow an extension equivalent to five turnings of the handle, if the multiplier is 5 or under, one push forward will do the same as five (or fewer) turns of the handle, and more than two pushes are never required.

In his last patent (from 1894), Selling attempted to design an electric calculating machine (with no engine, but through contacts and electromagnets), but apparently without any success.

The calculating machines of Eduard Selling demonstrated exceptional ideas and ingenuity but were complex and difficult for manufacturing and work, which is why they didn’t achieve any market success.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Unknown author / public domain