Leonardo Torres y Quevedo

Leonardo Torres y Quevedo was born on 28 December, 1852, on the Feast of the Holy Innocents, in a stone house (see the lower photo) in Santa Cruz de Iguña, a small village at north of Spain, near Molledo (Cantabria), Santander.

The house in Santa Cruz de Iguña, where Leonardo Torres was born in 1852

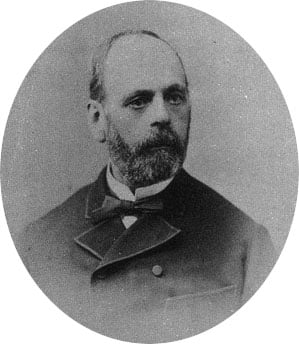

From his mother, Valentina Quevedo de la Maza, who was also born in Santa Cruz de Iguña, he inherited the Castilian austerity and her love to the highlands. From his father, Luis Gonzaga María Torres Urquijo, AKA Luis Torres de Vildósola y Urquijo (1818-1891), a civil engineer from Bilbao, he inherited his scientific rigour and his love for mathematics, a passion very useful in his long career as an inventor.

Luis Torres and his wife were very intelligent and strict people, who tried to devote as many as possible time to his family, but had to travel a lot. Besides Leonardo, they had a daughter, Joaquina Torres de Vildosola y Quevedo (born in 1851), and a younger son, Luis Torres Quevedo (born on 21 March 1855), who became a military officer and inventor with numerous patents in his name (e.g. a photographic machine from 1886).

Leonardo Torres as 7 years old (left photo) and 12 years old boy (right photo)

As a little boy Leonardo used to rummage about his father’s office, examining his engineering books, instruments and drawings.

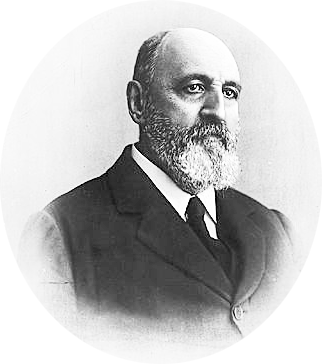

The family resided for the most part in Bilbao, where Luis Torres (see the nearby photo), a descendant of one of the most liberal families in Bilbao—Urquijo, worked as a railway engineer, although they also spent long periods in his mother’s family home in Santander’s mountains. In Bilbao Leonardo studied a bachelor school program at the Instituto de Enseñanzas Medias, and later spent two years (1868-1870) at the College of Brothers of the Christian Doctrine, Paris, to complete his studies. In 1870, his father was transferred, bringing his family to Madrid. In 1871 Leonardo began his higher education at the Civil Engineering Faculty of Madrid, where his father was already a professor. He temporarily suspended his studies in 1873 to volunteer for the defence of Bilbao, which had been surrounded by Carlist troops during the third Carlist war. Returning to Madrid, he completed his studies in 1876, fourth in his graduating class.

The family resided for the most part in Bilbao, where Luis Torres (see the nearby photo), a descendant of one of the most liberal families in Bilbao—Urquijo, worked as a railway engineer, although they also spent long periods in his mother’s family home in Santander’s mountains. In Bilbao Leonardo studied a bachelor school program at the Instituto de Enseñanzas Medias, and later spent two years (1868-1870) at the College of Brothers of the Christian Doctrine, Paris, to complete his studies. In 1870, his father was transferred, bringing his family to Madrid. In 1871 Leonardo began his higher education at the Civil Engineering Faculty of Madrid, where his father was already a professor. He temporarily suspended his studies in 1873 to volunteer for the defence of Bilbao, which had been surrounded by Carlist troops during the third Carlist war. Returning to Madrid, he completed his studies in 1876, fourth in his graduating class.

In the same 1876 Leonardo began his career with the same train company for which his father had worked, but soon he decided to resign from the railways and to dedicate himself to being a full-time inventor, concentrating on mechanical and electrical inventions. In fact, Leonardo was already a wealthy man, after receiving in late 1860s a substantial inheritance from a distant relative, Pilar Barrenechea. As a teenager, still in Bilbao, Leonardo was taken care of by the unmarried Barrenechea sisters, relatives of his father, and one of them, Pilar, declared him an heir of his property, which facilitated his future independence (she was a very wealthy person, who left in property and in money many millions of reals, and bequeathed her entire fortune to Leonardo). Thus he immediately set out on a long trip through Europe to get to know the state of the art in technology. He travelled to France, Switzerland and Italy, where he was mainly interested in everything related to electrical applications, e.g. in Paris he met some great scientists: Henry Poincare, Paul Appel and Maurice d’Ocagne.

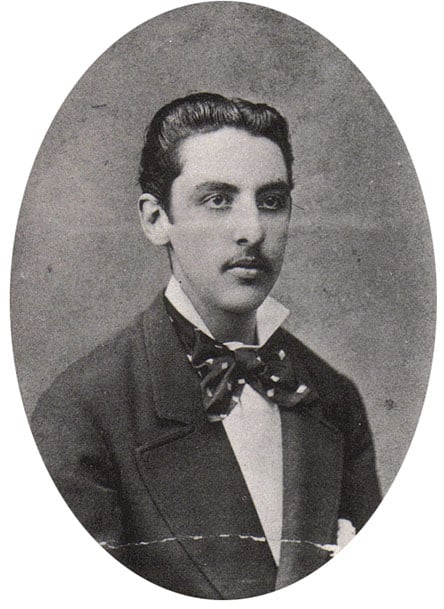

Leonardo Torres in 1873

Upon returning to Spain, on 16 April 1885 Leonardo Torres married in Portolín (Santander), to Maria Luz Niceta De Polanco y Navarro (1856-1954), a daughter of Miguel Polanco y Corvera (born 1818 in Santillana) and Julia Navarro y Trujillo (born 1833 in Madrid). They had eight children (4 boys and 4 girls: Leonardo (born 1887, died 2 years old in 1889), Gonzalo Torres-Quevedo y Polanco (born 1889, died 9 March 1965), Luz, Valentina, Luisa, Julia (also died young), Leonardo, and Fernando). The couple moved to Moledo-Portolin, a small village close to Santa Cruz de Iguña, where they spent first married years.

Leonardo Torres and his wife Luz Polanco y Navarro

It was in early 1880s, when Leonardo Torres started with inventions. Soon after his marriage, on 9 September, 1887, Torres received his first patent—in Germany, for a small funicular (so called transbordador or ferry). Soon he received a patent in Spain (Nr. 7348) for “A multi-wire aerial cableway system”, and in 1888 he extended this patent to United States, France, Italy, Canada, Great Britain, Prussia, Austria-Hungary, and Switzerland.

Later on Torres (and according to his patents) will design several other funiculars (cableways), the most famous of which is the Whirlpool Aero Car over the Niagara Falls in Ontario, Canada, started in 1913 and finished in August 1916 (directed by Torres himself and his son Gonzalo on place), and still working at present without having any problem in its over hundred years of working (see the lower photo). Other Torres’ funiculars have been installed successfully in Mount Ulia in the Basque Country, in Chamonix in the French Alps, and in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Quevedo’s Whirlpool Aero Car over the Niagara Falls in Ontario, Canada

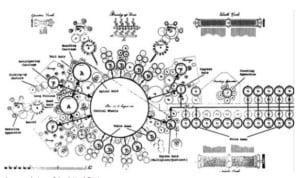

In the 1893 Torres presented his first paper to the Spanish Royal Academy of Sciences for an algebraic machine, able to calculate the roots of an any-grade equation and to print the solutions. That was the first automatic calculator built by Torres in a long list of them. This machine however has not been manufactured. The calculating machines of Torres are examined in an other article of this site.

In 1889 Torres moved to Madrid with the firm intention of carrying out the projects he had devised in previous years, and became involved in that city’s cultural life. In 1890 he made a trip to Switzerland, presenting his ferry project, but without getting the expected support. From the work he carried out in these years, the Athenaeum created the Laboratory of Applied Mechanics of which he was named director. The Laboratory dedicated itself to the manufacture of scientific instruments. That same year, he entered the Royal Academy of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences in Madrid, of which entity he was president in 1910.

Another field of interest for Torres was Aerostatics. He presented his first project for the airship to the Spanish and French Academies of Sciences in 1902, receiving immediately the recognition (later on he will receive patents for his airship). In 1906 he built his first dirigible balloon and two years later built the second one with the partnership of the French constructor Astra, whose company bought the patent. During WWI both French and English armies used Torres dirigibles in order to counteract the German Zeppelins (in the nearby photo you can see the second airship of Torres—Torres Quevedo №2, demonstrated in Guadalajara in 1908).

Another field of interest for Torres was Aerostatics. He presented his first project for the airship to the Spanish and French Academies of Sciences in 1902, receiving immediately the recognition (later on he will receive patents for his airship). In 1906 he built his first dirigible balloon and two years later built the second one with the partnership of the French constructor Astra, whose company bought the patent. During WWI both French and English armies used Torres dirigibles in order to counteract the German Zeppelins (in the nearby photo you can see the second airship of Torres—Torres Quevedo №2, demonstrated in Guadalajara in 1908).

Torres is also the inventor of an electronic device, widely used everyday—remote control. The work on Aerostatics drove Torres to the invention of so called Telekine, as he wanted to control the flight of dirigible balloons from ground, without risking human loves. He started work on this system in 1901 and in 1903 the Telekine was presented for the Academy of Sciences in Paris, in the same year, he obtained a patent in France, Spain, Great Britain, and the United States. In the patent he describes the Telekine so: It consists on a telegraph system, with or without wires, whose receiver sets the position of a switch, that switches on a servomotor, operating any mechanism. In 1906, in the presence of the Spanish king and before a great crowd, Torres successfully demonstrated the invention in the port of Bilbao, guiding a boat from the shore (see the nearby photo for the prototype of Telekine, from the Museum of Torres Quevedo in Madrid, source Antonio Yuste).

Torres is also the inventor of an electronic device, widely used everyday—remote control. The work on Aerostatics drove Torres to the invention of so called Telekine, as he wanted to control the flight of dirigible balloons from ground, without risking human loves. He started work on this system in 1901 and in 1903 the Telekine was presented for the Academy of Sciences in Paris, in the same year, he obtained a patent in France, Spain, Great Britain, and the United States. In the patent he describes the Telekine so: It consists on a telegraph system, with or without wires, whose receiver sets the position of a switch, that switches on a servomotor, operating any mechanism. In 1906, in the presence of the Spanish king and before a great crowd, Torres successfully demonstrated the invention in the port of Bilbao, guiding a boat from the shore (see the nearby photo for the prototype of Telekine, from the Museum of Torres Quevedo in Madrid, source Antonio Yuste).

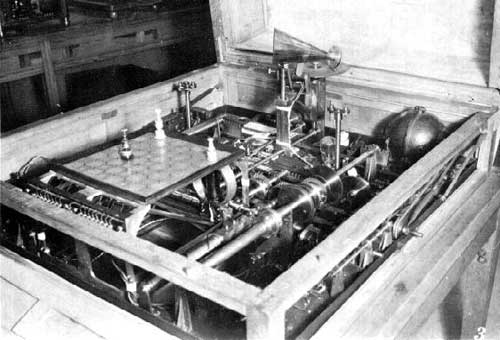

In 1911 Torres made and successfully demonstrated a chess-playing automaton for the end game of king and rook against king. This chess automaton was fully automatic, with electrical sensing of the pieces on the board and what was in effect a mechanical arm to move its own pieces. In 1920 Torres demonstrated a second chess automaton, which used magnets underneath the board to move the pieces (see the lower photo). Like a number of his other inventions, this one still exists and is still operational.

The second chess-automaton of Leonardo Torres

Leonardo Torres y Quevedo was highly estimated for his scientific achievements during his lifetime.

In 1916 the Spanish King Alfonso XIII bestowed the Echegaray Medal (the highest scientific award granted by the Royal Spanish Academy) upon him (see the lower photo from the event). In 1918, Torres declined the offer of the position of Minister of Development. In 1920, he entered the Royal Spanish Academy, in the seat that had been occupied by Benito Pérez Galdós, and became a member of the department of Mechanics of the Paris Academy of Science. In 1922 the Sorbonne named him an Honorary Doctor and, in 1927, he was named one of the twelve associated members of the Academy.

In 1916 King Alfonso XIII bestowed the Echegaray Medal upon Leonardo Torres

In his speech upon the entering of the Royal Spanish Academy Leonardo Torres was so humble and funny:

You were wrong in choosing me as I do not have that minimum culture required of an academic. I will always be a stranger in your wise and learned society. I come from very remote lands. I have not cultivated literature, nor art, nor philosophy, nor even science, at least in its higher degrees… My work is much more modest. I spend my busy life solving practical mechanics problems. My laboratory is a locksmith shop, more complete, better assembled than those usually known by that name; but destined, like all, to project and build mechanisms…

Leonardo Torres y Quevedo died in the heat of the Spanish Civil War in the early hours of 18 December 1936, at the home of his son, Gonzalo Torres-Quevedo y Polanco (who also became an engineer, and used to work as an assistant of his father), in Madrid.

Up Next…

Interested in finding out about other influential individuals who changed our world forever? Read the following articles below:

- George Stibitz – Complete Biography, History and Inventions: As a child, he very nearly set his home on fire owing to an obsession with electricity. He would grow up to become an inventor and computer pioneer. Discover all you need to know about the man who invented the first digital computer, among other things.

- Charles Stanhope – Biography, History and Inventions: Born to nobility, he was a statesman, scientist, and inventor. Discover his interests as well as the devices he designed.

- Brainard Fowler Smith – Biography, History, and Inventions: Once California cast its spell on him he decided to remain there forever — and settle down to the art of invention. Find out what he created and how he did it.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©G-Stock Studio/Shutterstock.com.