©Colombini, Cosomo, -1812, engraver, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – Original / License

The Sketch of Leonardo da Vinci

(Created with the expert advice of Mr. Silvio Hénin, Milan, Italy)

Leonardo da Vinci (see biography of Leonardo da Vinci) is probably the most diversely talented person ever to have lived. He was a remarkable painter, engineer, anatomist, architect, sculptor, musician, etc. During his life, Leonardo produced thousands of pages of perfectly illustrated notes, sketches, and designs. A part of these pages (only half of almost 13000 original pages), as impressive and innovative, as his artistic work, managed to survive to our time. They are collected now in 20 notebooks (so-called codices), comprising some 6000 pages. These codices decorate expositions of many museums (the only codex, that is in private hands is the Codex Leicester, a small volume of only 36 pages, which was purchased in 1994 by Bill Gates for $30.8 million).

Some of the documents were so thoroughly lost, that they weren’t found again until the last few decades! In February 1965, an amazing discovery was made by Dr. Julius Piccus, Professor of Romance Languages in Boston, working in the Biblioteca Nacional de España (National Library of Spain) in Madrid, who was searching for medieval Spanish ballads and troubadours. Instead of ballads, searching in some cabinets, he stumbled upon two unknown collections of Leonardo’s manuscripts, bound in red Moroccan leather, which were known by the Spanish librarians, but were not described yet (the public officials stated that the manuscripts “weren’t lost, but just misplaced”, because of an error in the catalog).

These manuscripts were in the collection of the sixteenth-century Italian sculptor Pompeo Leoni (1533-1608) and were taken by him to Spain, to be offered to the Spanish King Felipe II in the 1590s. For some reason however Leoni kept the collection in his house, and after his death, it was divided into several parts, which went to England, France, and Italy, but few remained in Spain and in 1642 were donated to King Felipe IV, to become later a part of the Royal Library (later Biblioteca Nacional) in Madrid. These manuscripts (almost 700 pages, on subjects such as architecture, geometry, music, mechanics, navigation, and maps) are now referred to as Madrid Manuscripts or Codex Madrid I and Codex Madrid II.

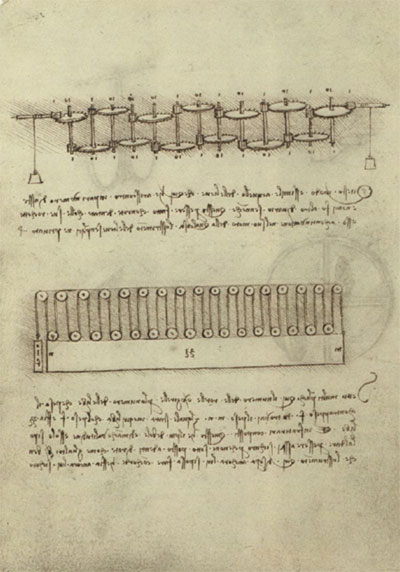

Codex Madrid I (composed of 192 pages with a size of 21/15 cm) is an engineer’s delight treatise on mechanics, full of perfectly drawn and laid out gadgets, gears, and inventions. It was compiled by Leonardo in 1493 when he served at the Castle of Milan under Duke Ludovico il Moro. Codex Madrid I was not put together after Leonardo’s death (which is for example what happened with the miscellaneous contents of the Codex Atlanticus, the largest collection of Leonardo’s manuscripts). It was in fact Leonardo himself who put it together and it has survived almost intact, except for 16 pages, which have been torn out and seem to have been lost. Codex Madrid I can be called the first and most complete treatise in the history of Renaissance mechanics, and in it, there is a sketch, picturing a mechanism, which is very likely to be designed for calculating purposes.

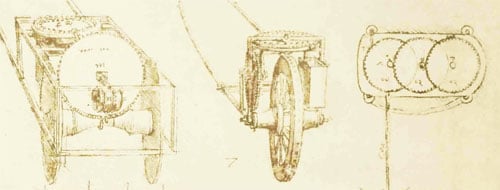

Page 36 verso (back) of Codex Madrid I (the interesting for us sketch is the upper one, as the lower sketch is picturing a multiple pulley mechanism)

The gear wheels in the figure are enumerated as follows: the small wheels are enumerated with 1, while the bigger wheels are enumerated with 10 (take into account, that in this case Leonardo, as in many of his writings, writes laterally inverted from right to left!).

The text bellow the figure is written using the strange 15th century Italian language of Leonardo, again inverted, and it is not very informative – Questo modo è ssimile a cquello delle lieve che qui è a risscontro in pari numero di asste. E non ci fo altro divario sennonchè quessto, per essere fatto con rote dentate colle sue rochette, esso ha continuatione nel suo moto, della qual cosa lo sstrumento delle lieve senplici n’è privato

The language of Leonardo is never easy to understand, because it is indeed quite cryptic and his writings are more private notes, than clear explanations for readers. A rough translation of the text below the figure is: “This manner is similar to that of the levers, although different, because, being this made of gears with their pinions, it can move continuously, while the levers cannot.”

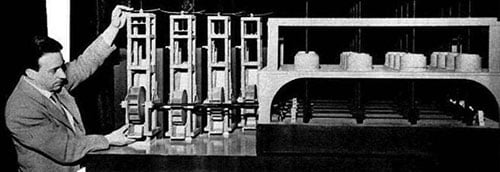

The Italian engineer from Milan, Dr. Roberto A. Guatelli (1904-1993), was a world-renowned expert of Leonardo da Vinci, who had specialized in building working replicas of Leonardo’s machines since the early 1930s. When in the late 1930s they went on exhibit, Italian dictator Mussolini was so pleased with this great example of Italy’s engineering heritage, that he decided to fund a traveling exhibition to impress the whole world.

Guatelli and his exhibition were in the US in 1940, when World War II broke out. He was forced to flee to Japan with his models but returned to the US after the war. Soon Guatelli began rebuilding his models (the initial collection was destroyed during WWII) and created a lot of new replicas (not only of Leonardo’s machines, but also of other, mainly calculating devices, like Pascalene of Blaise Pascal, Stepped Reckoner of Gottfried Leibniz, tabulating machine of Herman Hollerith, and differential engine of Charles Babbage) with four assistants, including his chief aid, his stepson Joseph Mirabella.

In 1951 the president of IBM Thomas Watson Sr. saw Guatelli’s collection, and recognizing his genius, he bought the collection and hired him to rebuild more of his models for IBM, which then toured them as a corporate-sponsored exhibition. IBM placed a workshop at Guatelli’s disposal and organized traveling tours of his replicas (see the upper image of Guatelli, demonstrating one of his models), which were displayed at museums, schools, offices, labs, galleries, etc.

In 1967, shortly after the discovery of the Madrid Manuscripts, Guatelli went to the library of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), to examine its copy of the manuscripts. When seeing the page with the above-mentioned sketch, he remembered seeing a similar drawing in Codex Atlanticus. In fact, Codex Atlanticus contains a lot of gear-wheel transmissions, see for example the lower sketch.

The left and the middle drawings are of hodometers, devices for measuring distance, known for many centuries (it seems the first odometer was described by Heron of Alexandria, who used an analog train of gear wheels (linked so that each time one wheel completes a revolution the next wheel turns one-tenth of a revolution, thus recording a carry), while the right drawing is of a ratio mechanism. Leonardo certainly was not the inventor of gear-wheels and the hodometer, and he knew very well at least the fundamental treatise of Vitruvius — De architectura, written about 15 BC. In Book X, Chapter IX of this treatise is described a hodometer with gear-wheels and a carry mechanism.

Putting the two above-mentioned drawings together, Dr. Guatelli built a hypothetical replica of Leonardo’s calculating device in 1968 (see the lower photo). It was displayed in the IBM exhibition.

The text beside the replica said:

Device for Calculation: An early version of today’s complicated calculator, Leonardo’s mechanism maintains a constant ratio of ten to one in each of its 13 digit-registering wheels. For each complete revolution of the first handle, the unit wheel is turned slightly to register a new digit ranging from zero to nine. Consistent with the ten to one ratio, the tenth revolution of the first handle causes the unit wheel to complete its first revolution and register zero, which in turn drives the decimal wheel from zero to one. Each additional wheel marking hundreds, thousands, etc., operates on the same ratio. Slight refinements were made on Leonardo’s original sketch to give the viewer a clearer picture of how each of the 13 wheels can be independently operated and yet maintain the ten to one ratio. Leonardo’s sketch shows weights to demonstrate the equability of the machine.

After a year the controversy regarding the replica had grown and an interesting Academic trial was then held at the Massachusetts Technological University, in order to ascertain the reliability of the replica.

Amongst others were present I. Bernard Cohen (1914-2003), professor of the history of science at Harvard University — consultant for the IBM collection, and Dr. Bern Dibner (1897-1988) — an engineer, industrialist, and historian of science and technology.

The objectors claimed that Leonardo’s drawing was not of a calculator, but actually represented a ratio machine. One revolution of the first shaft would give rise to 10 revolutions of the second shaft, and 10 to the power of 13 at the last shaft. And what is more, such a machine could not be built, due to the enormous amount of friction that would result. Dr. Guatelli managed to build a replica, but the technology in the 15th century was so primitive, compared to ours, so a working machine cannot be built.

It was stated that Dr. Guatelli had used his own intuition and imagination to go beyond the statements of Leonardo

The vote was a tie, but nonetheless, IBM decided to remove the controversial replica from its display.

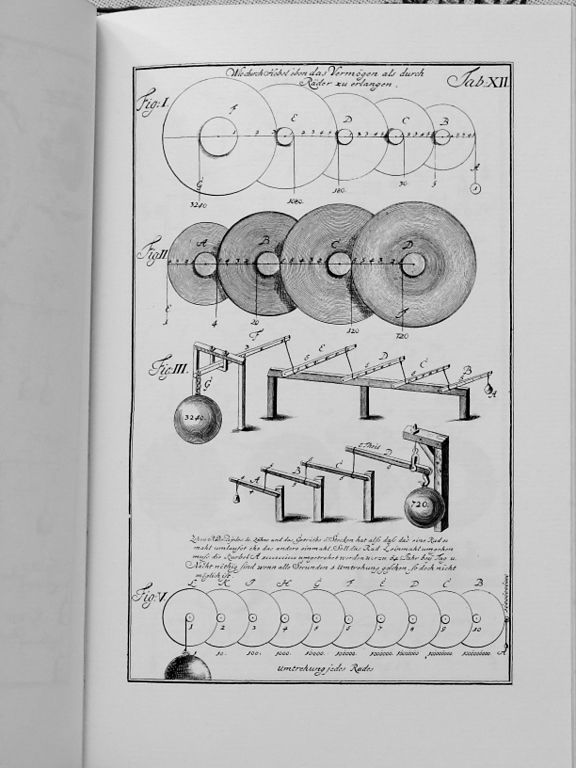

It seems the objectors were right because such mechanisms were quite popular several centuries ago. A similar mechanism for example can be seen (see the lower image) in the famous encyclopedia Theatrum Machinarum of Jacob Leupold

©Jacob Leupold, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – Original / License

Mr. Silvio Hénin from Milan (the author of historical investigations for the machines of other Italian inventors, like Torchi and Gonnella), also thinks that Guatelli was almost certainly wrong. Mr. Hénin was so kind to give his expert opinion regarding this matter:

Leonardo was possibly studying the properties of gear trains in comparison with systems of levers; both can multiply forces (torques), but only gears can produce a continuous movement. In the other direction the gear train can multiply rotation speed. In the same page, in fact, a compound pulley system is shown, which has the same force-multiplying properties as a gear train, a demonstration of what Leonardo was examining.

I can only add some points:

1. Leonardo’s drawing does not show any numbering on the gear wheels (mandatory for a calculator).

2. No way to set the operands is shown (which is mandatory).

3. No way (e.g. ratchet) to stop the wheels in precise discrete positions (which is mandatory) is shown.

4. Two weights are shown at the two ends (useless in a calculator).

5. The use of 13 decimal figures for calculations in XV century is quite a nonsense.

The bottom line is: Even if the mechanism of Leonardo was designed for calculating purposes, it was probably not built and had no influence over the further development of mechanical calculating devices.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Unknown author / public domain