Key Points:

- Konrad Zuse is known for designing the S2 computing machine, one of the first electronic calculating machines that had over 2000 vacuum tubes.

- In 1938, Zuze built the Z1, a reliable computing machine which was able to compute the determinant of a three-by-three matrix and had an incredibly solid design layout.

- The measurement apparatus in the S2 model is probably the first known analog-to-digital converter ever built, but it was never deployed in production.

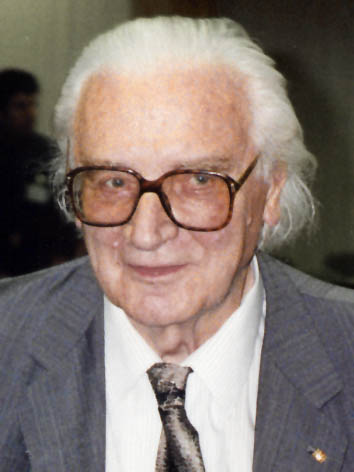

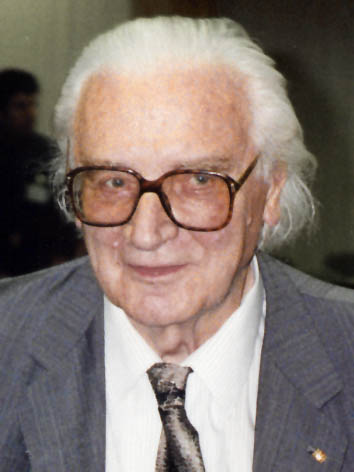

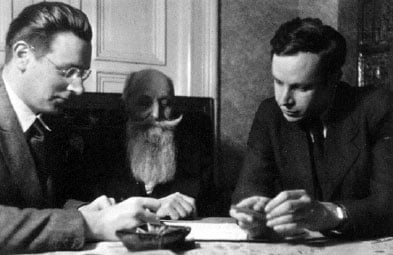

Konrad Zuse was a German civil engineer, computer scientist, inventor, and businessman.

©Wolfgang Hunscher, Dortmund, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons – License

Who Was Konrad Zuse?

Konrad Zuse was a German civil engineer, computer scientist, inventor, and businessman. He was born in 1910 in Berlin, Germany. Zuse received a PhD in civil engineering from the Technical University of Berlin in 1934.

Zuse gained prominence for the S2 computing machine , invented in 1936. The S2 was one of the first electronic calculating machines and had over 2000 vacuum tubes. It reached a top speed of only 10 operations per second, but was considered to be an improvement on previous mechanical devices such as Enigma.

Quick Facts

- Full Name

- Konrad Zuse

- Birth

- June 22, 1910

- Death

- December 18, 1995

- Net Worth

- N/A

- Awards

- Werner Von Siemens Ring

- Children

- Horst Suze

- Nationality

- German

- Place of Birth

- Berlin, German Empire

- Fields of Expertise

- [“Mathematics”,”Computer Science”,”Mechanical Engineering”]

- Institutions

- Technical University of Berlin

- Contributions

- Z3 machine

Because of the second world war, Zuse’s work did not gain much ground in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Early Life

Konrad Zuse was born in Berlin on June 22 1910. In 1912, his family moved to Braniewo, Poland where his father worked as a postal clerk.

In 1912, the Zuse family left for Braunsberg, a sleepy small town in east Prussia, where Emil Zuse was appointed a postal clerk. From his early childhood Konrad started to demonstrate a huge talent, but not in mathematics, or engineering, but in painting (look at the fabulous chalk drawing nearby, made by Zuse in his school-time).

Konrad went too young to the school and enrolled in the humanistic Gymnasium Hosianum in Braunsberg. After his family moved to Hoyerswerda (Hoyerswerda is a town in the German Bundesland of Saxony), he passed his Abitur (abitur is the word commonly used in Germany for the final exams young adults take at the end of their secondary education) at Reform-Real-Gymnasium in Hoyerswerda.

After graduation the young Konrad fell into a state of uncertainty, what to study later—engineering or painting. The film Metropolis of Fritz Lang from 1927 impressed Konrad. He dreamed of designing and building a giant and impressive futuristic city as Metropolis and even started to draw some projects. So he finally faced facts and he decided to study civil engineering at the Technical College (Technischen Hochschule) in Berlin-Charlottenburg.

During his study he also worked as a bricklayer and bridge builder. During this time the traffic lights were introduced into Berlin, causing a total chaos in the traffic. Zuse was one of the first people, who tried to design something like a “green wave”, but was unsuccessful.

He was also very interested in the field of photography, and designed an automated system for development of band negatives, using punch cards as accompanying maps for control purposes. Later on he devised a special system for film projections, so called Elliptisches Kino

Zuse’s interest in engineering started at around age 15 when he took apart a clock and reassembled it after painting the pieces black so that they could not be discerned from one another. He also built his own radio receiver with a small group of friends. In 1928, Zuse served briefly in the army before returning to Berlin and completing his civil service training as an engineer officer in 1929.

Career

After his studies, he became interested in automating repetitive tasks and created one of Germany’s first computers later called ‘Z1’.

Konrad Zuse is an inventor with some claim to fame for creating mechanical constructions as well as designing bridges, cranes etc., eventually finding that his interest lay more within engineering rather than architecture or graphic design.

After his graduation in 1935, Zuse started working as a stress analyst for the plane manufacturer Henschel Flugzeugwerke. However, he resigned from this position with the intent of starting his own company. His goal was to create automatic calculating machines and had already made contact with Kurt Pannke, a builder of desk-style calculators.

Although Konrad Zuse’s service at Henschel proved crucial to his career, he was ultimately conscripted into the German army.

Konrad Zuse constructed the first working computer. To fund its construction he received financial support from his parents and various friends, students at university assisted him by working on the machine for free in their spare time, while others contributed to the cause with small donations so that he would be able to complete what became known as “V1″- or “experimental model one”.

One of the most important facts between Zuse and other computer inventors working in the late 1930s was that he had to design his machine all by himself, whereas scientists such as John Atanasoff and Howard Aiken had university or company resources available at their disposal. The mechanical conception of the V1 (later renamed to Z1) came entirely from his brainchild.

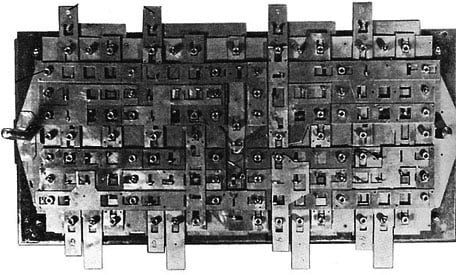

The Z1, a reliable computing machine created in 1938 by Konrad Zuse, was able to compute the determinant of a three-by-three matrix and had an incredibly solid design layout. Even though it was not flawless in its mechanics, the mechanical capabilities included proved sound when compared to other machines at the time.

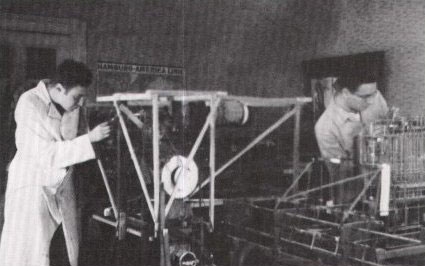

Zuse Z1 replica in the German Museum of Technology in Berlin

©ComputerGeek, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons – License

Following this, consideration could be given to an electrical realization, using telephone relays. It was suggested that vacuum tubes may have difficulty with the complexity of calculations.

Helmut Schreyer, a college friend of Zuse and electronics engineer said he would pursue these developments for his PhD project.

Though vacuum tubes promised extremely fast calculations, Konrad Zuse was not convinced of their reliability. Instead he doubted the long-term viability of these devices and thought about possible uses for his machine.

There were many aspects of the new world that fascinated Konrad Zuse. The questions surrounding technology and its impact on society intrigued him, but he also found things like jazz music to be fascinating in a time when all other composers seemed to have fallen into an artistic coma.

Zuse wondered what could be causing this stagnation in arts and is appalled at how disengaged from reality artists had become. He soon realized that following one’s own interests was the key to success.

Originally, Konrad Zuse planned to create a mechanical desktop calculator that could be replaced with a new computing machine. However, he found himself drawn more towards electronic innovations.

In 1938, Schreyer and Zuse explained some of the electronic circuits to a small group at the Technische Hochschule. When asked how many vacuum tubes would be needed for a computing machine, they replied that two thousand tubes and several thousand other components would be enough.

Academic scholars were skeptical of vacuum-tube circuitry at the time, which was limited to less than hundred tubes in the most advanced designs. However, only six years later a machine operator Philadelphia would show that this type of circuitry was feasible and not nearly as expensive as they had believed so far.

World War II interfered with Konrad Zuse’s engineering duties. During his service, he learned that Kurt Pannke had convinced superiors to transfer Zuse to Berlin where the next computing machine could be built.

To speed up Zuse’s discharge, Konrad went to the military with an offer of building them a machine that could be operational in two years. His offer was met with sarcasm as officials reminded him that the war would have ended by then.

Finally, his former superiors at Henschel were able to obtain Zuse’s transfer to the airplane factory in Berlin-Adlershof where he was hired to make calculations necessary for correcting wings in flying bombs.

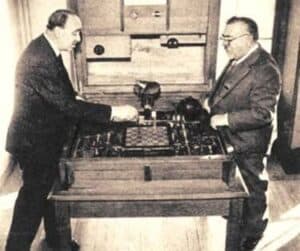

The World’s First Programmable Computer

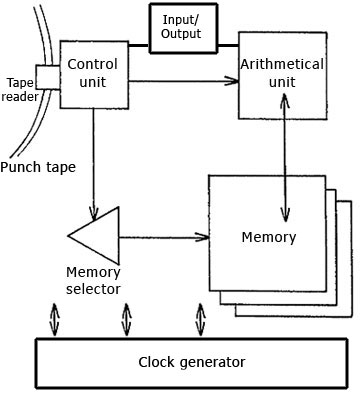

In 1940, Konrad Zuse started working for a special section of Henschel’s factory. For the next five years he developed S1 and S2 machines. The latter, which could automatically measure some parameters of missile wings, transform analog measurements into digital numbers, and compute corrections based on these values.

The S1 version of his control box used a manual decimal keyboard, while the later versions used an automatic selector movement and coded instructions. The measurement apparatus in the S2 model is probably the first known analog-to-digital converter ever built, but it was never deployed in production.

The Z2, an experimental model that used a mechanical memory cannibalized from the Z1 and had the same logical design of the Z1 was operational in 1940.

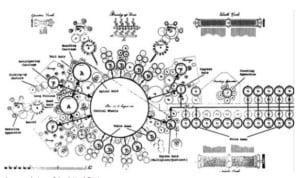

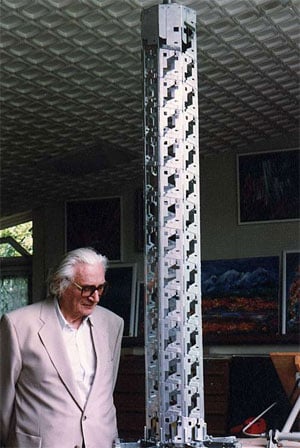

Helix Tower

In 1992 Zuse started his last project—the Helix-Tower (see the lower image), a variable height tower, for catching wind in order to produce energy in an easier way, build from uniformly shaped and repeatable elements. The propeller and wind generator had to be mounted on the top of the tower. Zuse used a very elegant mechanical construction and immediately received a patent for this in 1993. The height of the tower could be modified by adding or subtracting building blocks.

What Was Konrad Zuse Known For?

His greatest achievement was the world’s first functional program-controlled Turing complete computer, the Z3. The program was stored on a punched tape. He received the Werner von Siemens Ring in 1964 for this design.

Zuse also designed the first high-level programming language, Plankalkül, and it went largely ignored when he published it in 1948. One inventor of ALGOL (Rutishauser) wrote that “the very first attempt to devise an algorithmic language was undertaken in 1948 by K. Zuse.”

Zuse Z3 replica on display at Deutsches Museum in Munich

©Venusianer, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons – License

Zuse was more than just an engineer. He started his own computer company to build the Z4, which became the second commercial computer rented out by ETH Zürich in 1950.

Despite the focus of World War II on Zuse’s device in Europe, it was largely ignored by American and British industries. The only visible progress America had made with this technology was during a 1946 offer from IBM to license some patents. However, Zuse contributed two other inventions that are still respected today: in 1968 he presented the concept of Calculating Space (a computation-based universe) and donated one replica model of his calculating machine as well as another replicating his successor, the Z4. These models are now on display at Deutsches Museum in Munich, Germany, which immortalized Zuse even after death.

Z4 on display at the Deutsches Museum, Munich

©Clemens PFEIFFER, CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons – License

Konrad Zuse: Marriage, Children and Personal Life

In January 1945, Konrad Zuse married his wife Gisela Brandes. He hired a carriage to deliver him in a tailcoat and top hat. His fiancée Gisela wore a wedding veil for the ceremony, which was attended by many relatives and friends.

The couple had their first son Horst in November 1945.

Although Zuse never became a party member, he is not known to have expressed any qualms about working for the Nazi war effort. In retrospect, considering his feelings about modern times and scientists being forced to work for questionable business and military interests in the Faustian bargain, it is understandable how larger implications may not have occurred to him.

Zuse is infamous for inventing the Z4, the predecessor to what would become known as a computer. After he retired, he focused on his interest in painting. His death was on 18 December 1995 of heart failure, near Fulda (Hesse). His achievements have been highly regarded even after his death.

Konrad Zuse: Awards and Achievements

Zuse received many honors for his contributions to the field, including:

- The Werner von Siemens Ring in 1964 (shared with Fritz Leonhardt and Walter Schottky)

- Harry H. Goode Memorial Award in 1965 (shared with George Stibitz)

- The Wilhelm Exner Medal in 1969

- The Bundesverdienstkreuz award (Grand Cross of Merit) in 1972

Two medals, one from the Gesellschaft für Informatik and the other from the Zentralverband des Deutschen Baugewerbes (Central Association of German Construction), are both named after Konrad Zuse.

There is a replica of the Z3 as well as an original Z4 in the Deutsches Museum in Munich. Additionally, there is an exhibition devoted to Zuse at the Der Deutsche Technikmuseum Berlin, displaying twelve machines he made including replicas of the Z1 and several paintings by him.

To honor the 100 year anniversary of his birth, over the course of a series of lectures, exhibitions and workshops.

Konrad Zuse: Published Works

In 1969 Zuse published Rechnender Raum, the first book on digital physics. He proposed that the universe is being computed by some sort of cellular automaton or other discrete computing machinery, challenging the long-held view that some physical laws are continuous by nature. He focused on cellular automata as a possible substrate of the computation, and pointed out that the classical notions of entropy and its growth do not make sense in deterministically computed universes.

In 1970, Zuse published his autobiography, The Computer-My Life.

Up Next…

- The History of Colossus Computer Find out everything there is to know about Colossus supercomputer.

- The Best 10 Robotics YouTube Channels There’s a lot of valuable resources for those interested in robotics. We’ve provided our top 10 picks of the best robotics channels on Youtube.

- Steve Jobs — Complete Biography, History and Inventions Learn about the tech pioneer Steve Jobs in this fascinating biography.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Wolfgang Hunscher, Dortmund, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.