Key Points:

- Karel Čapek delved into science fiction with several novels and plays including War with the Newts, published in 1936. His 1921 play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) introduced the word “robot” for the first time.

- Čapek was an avowed anti-fascist and anti-communist who was ranked as “public enemy number 2” in Czechoslovakia by the Gestapo.

- An asteroid discovered by Lubos Kohoutek in 1931 was named after Čapek.

Who was Karel Čapek?

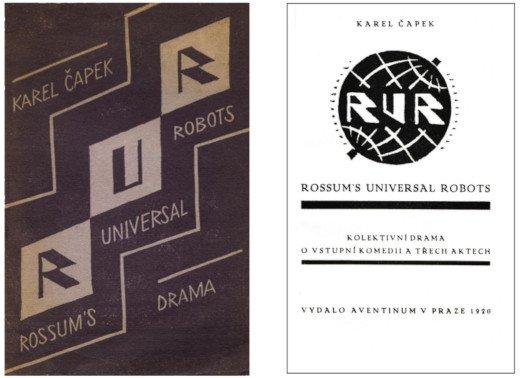

Karel Čapek was a critic, playwright, and novelist who wrote science fiction before it was officially a genre. He is known for several novels and plays including, War with the Newts which was published in 1936, and the play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) in January 1921. This particular play introduced the word “robot” for the first time.

Čapek also wrote several political works that dealt with difficult and emotionally charged issues of his time. He was a strong supporter of free expression and opposed both communism and fascism in Europe. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature a total of seven times but never won. There are, however, several awards associated with his name. He also worked in close collaboration on many projects with his brother, Josef Čapek.

Quick Facts

- Full Name

- Karel Čapek

- Birth

- July 26, 1855

- Death

- December 25, 1938

- Net Worth

- N/A

- Awards

- He had an asteroid named after him

- received the Order of Tomas Garrigue Masarynk, in memoriam, in 1991

- Children

- N/A

- Nationality

- Czechoslovakian

- Place of Birth

- Czech Republic

- Fields of Expertise

- [“Science Fiction”]

- Institutions

- N/A

- Contributions

- He wrote several novels, plays, and short stories. He and his brother Josef Čapek, are credited with the invention of the word robot. One of his most famous works is R.U.R (Rossum’s Universal Robots).

Early life

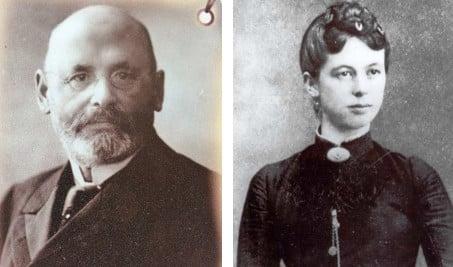

On November 6, 1884, Antonin Čapek married the young Božena Novotná (May 26, 1866–April 13, 1924), the daughter of Karel Novotný (1837-1900) from Hronov, horses and grain trader, and miller, and his wife Helena Novotná (1841-1912). The couple had three children — Josef, Helena, and the youngest, Karel.

Karel grew up in Úpice, where from 1895 until 1901 he attended the local primary school (Volkschule and the first class of Stadtschule). He was very sick as a small child with spinal problems, and would remain so for the majority of his life. Because he was the youngest, and in poor health, he was lavished with attention at home.

In 1901, Karel entered the Gymnasium in Hradec Králové. There he joined a secret student discussion club and participated in the publication of the magazine Obzor. This activity was unacceptable for the Austro-Hungarian authorities at that time, and he was advised to leave the school.

In 1905, the family decided that Karel would be transferred to the First Czech Gymnasium in Brno because his older sister Helena was married to an important Brno lawyer there, Karel Koželuh. In August 1907, the whole family moved to Prague, where Karel studied at the Academic Gymnasium until 1909.

From 1909 until 1915, Karel studied philosophy, aesthetics, art history, German, English, and Czech at the Faculty of Arts at Charles University in Prague (with a year-long interruption because of his stay at the University of Berlin and especially in Paris, where his brother Josef Čapek was at that time). In November 1915, he received a doctor’s degree in philosophy.

In 1920 Karel Čapek met the young actress Olga Scheinpflugová, the daughter of the writer, journalist, and playwright Karel Scheinpflug. After 15 years, they were married on August 26, 1935. The newlyweds received a house in Stará Huť near the municipality Dobříš–Strž from Václav Palivec for lifelong use.

Career

Phase 1

Starting in early 1917, Karel Čapek worked as a private tutor of Prokop Lažanský (a Czech nobleman) at the castle in Chýše by Žlutice. In October he started as an editor of the National Journal (Národní listy). He was spared compulsory military service during World War I because of his spinal problems.

Karel Čapek was an avowed anti-fascist and anti-communist. He had to face a campaign of hate from the right-oriented press after the Munich Conference. The Gestapo had ranked him as “public enemy number 2” in Czechoslovakia. He was a great Anglophile since he was a schoolboy, and later became a friend of President Masaryk.

Phase 2

From 1921 until 1938, Karel worked as an editor at the Prague editorial board of People’s News (Lidové noviny). In 1921-1923, he was a script editor and director at the Royal Vineyards City Theater. He then went on to become a novelist, writing many of the first types of science fiction.

He wrote many plays and novels throughout the 1920s and 1930s. In the 1930s, Čapek was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature several times (mainly for his plays R.U.R., The Makropulos Affair, and novel War with the Newts, but he never won it. He was, however, a talented novelist with the ability to tell an intriguing story.

©http://www.nndb.com/people/951/000113612/, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – Original / License

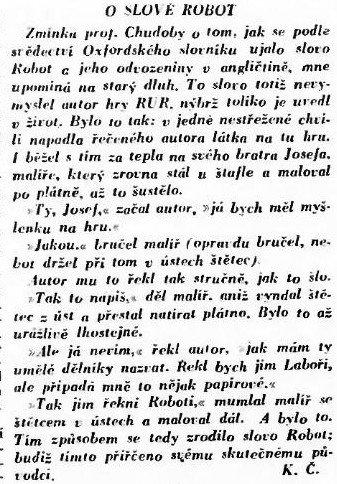

Regarding the history of the word “robot,” this is considered an invention that came out of his writing of science fiction. Karel Čapek described the occasion approximately 13 years later in the newspaper Lidové noviny, on December 24, 1933. The text, written in English, and the original report, appears below:

The note of prof. Chudoba about mentioning of the Robot word in Oxford dictionary and its derivation in English, reminds me that I have an old duty. The author of the play RUR did not, in fact, invent that word, he merely ushered it into existence. It was like this: the idea for the play came to said author in a single, unexpected moment. And while it was still fresh he rushed immediately to his brother Josef, a painter, who was just standing by the easel, vigorously painting at a canvas.

“Listen, Josef,” the author began, “I think I have an idea for a play.”

“What kind of?” the painter mumbled (he really did mumble, because at the moment he was holding a brush in his mouth). The author told him as concisely as he could.

“Then write it,” the painter said, without taking the brush from his mouth or stopping to work on the canvas. His indifference was quite insulting.

“But,” the author said, “I don’t know what to call those artificial workers. I could call them Laboři, but that strikes me as a bit literal.”

“Then call them Roboti,” the painter muttered, brush in mouth, and carried on painting. So it happened…

The word robot actually is derived from the word robota, which means “serf labor.” This translates to “hard work” or “drudgery” in Czech. Robots are an inventions that are examples of automata, which are programmed to mimic human movement and activity.

Further inspiration for robots came at the beginning of 1920 when Karel took a tram from Prague’s suburbs to the city center. The tram was so uncomfortably overcrowded, that people were pressed together inside, even spilling outside onto the tram steps, appearing not like herded sheep, but like machines. Thus Karel imagined people not as individuals but as machines and during the journey thought about an expression that would describe a human being only able to work but not able to reason.

With that in mind, in the spring of 1920, Karel began to write a story about the manufacture of artificial people from synthetic organic material who would free humans of work and drudgery, but finally due to overproduction those roboti would lead humankind to destruction and annihilation.

The play describes the activities of R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) company that makes artificial people from man-made synthetic, organic matter. These beings are not mechanical creatures, as they may be mistaken for humans and can think for themselves. Initially, they seem happy to work for humans, but that changes with time, and in the end a hostile robot revolt points to the extinction of the human race.

R.U.R. premiered in January 1921 and quickly became famous and influential in both Europe and North America. By 1923, it had been translated into thirty languages. The play was described as “thought-provoking”, “a highly original thriller”, “a play of exorbitant wit and almost demonic energy” and was considered as one of the “classic titles” of inter-war science fiction. Since then, and almost immediately, the robot word has become a universal expression in most languages for artificial intelligence machines, invented by humans.

In November 1938, Čapek caught a cold and fell ill with influenza and pneumonia. Being a heavy smoker, and after improper treatment, he died of pneumonia on Sunday, December 25, 1938, shortly before his 49th birthday. His body was interred in the Vysehrad cemetery on December 29th.

Karel Čapek: Marriage, Divorce, Children, and Personal Life

Marriage

Karel Čapek married Olga Scheinpflugová on August 26, 1935. The marriage did not produce any children.

Tragedy

Karel Čapek had health problems throughout his life. In particular, he suffered from a spinal disability.

Karel Čapek: Awards and Achievements

The following are three specific awards that Čapek received or that were given in his name.

Award 1

An asteroid discovered by Lubos Kohoutek in 1931 was named after Čapek.

Award 2

Čapek received the Order of Tomas Garrigue Masarynk, in memoriam, in 1991.

Award 3

Richard E. Pattis named the Karel (Programming Language) for Čapek.

Published Works and Books

Karel Čapek published several books during his lifetime. The following are several novels he published.

Novels

- 1922 – The Absolute at Large

- 1922 – Krakatit

- 1933 – Hordubal

- 1934 – Meteor

- 1934 – An Ordinary Life

- 1936 – War with the Newts

- 1937 – The First Rescue Party

- 1939- Life and Work of Composer Foltvn

Travel Books

Travel books he wrote include Letters from Italy, Letters from England, Letters from Spain, Letters from Holland, and Travels in the North.

In addition to these novels and travel books he wrote several detective stores and fairy tales. He also co-wrote the libretto for the opera Lásky hra osudná in 1922. This was a collaboration with his brother Josef.

Plays

- 1920 – The Outlaw

- 1920 – R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). This play features one of the first examples of AI in literature.

- 1921 – Pictures from the Insect’s Life

- 1922 – The Makropulos Affair

- 1927 – Adam the Creator

- 1937 – The White Disease

- 1938 – The Mother

The image featured at the top of this post is ©http://www.nndb.com/people/951/000113612/, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – License / Original