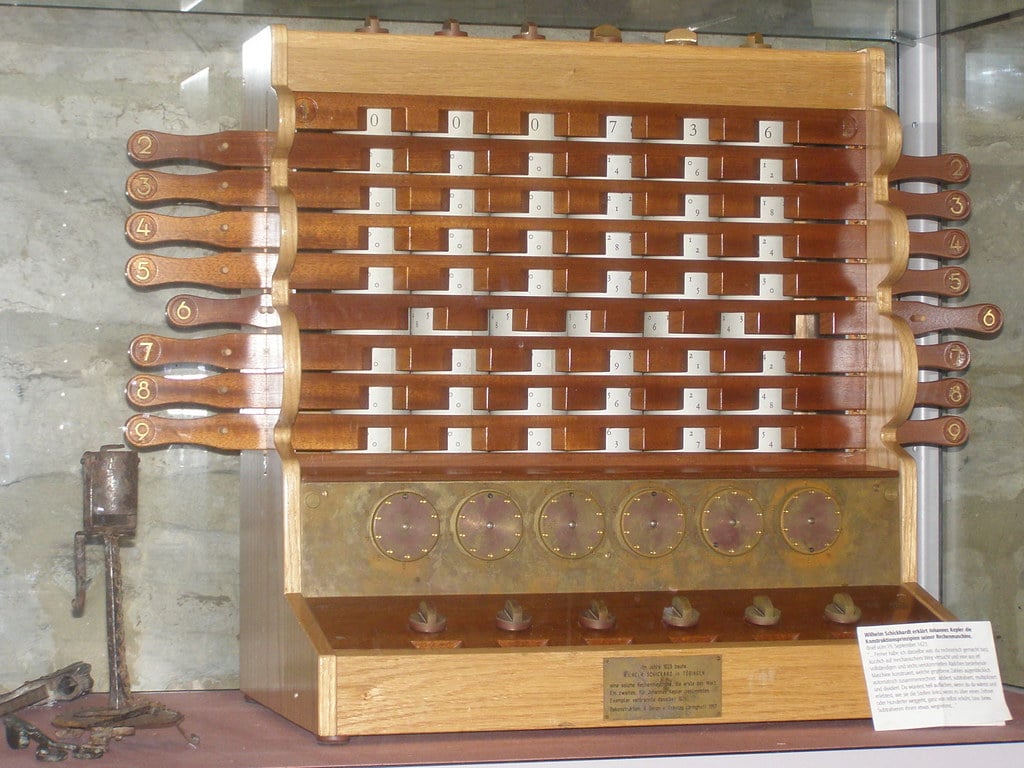

Wilhelm Schickard

Early Life

Wilhelm Schickard (see the calculating machine of Schickard) was born in the morning at half past seven on 22 April 1592, in Herrenberg, Germany. Herrenberg is a small town, located in the Württemberg area in the southern part of Germany, some 15 km from one of the oldest university centers in Europe —Tübingen, whose University was founded in 1477.

Wilhelm was the first child in the family of Lukas Schickard (1560-1602), a carpenter and master builder from Herrenberg, who wed Margarethe Gmelin-Schickard (1567-1634), a daughter of Wilhelm Gmelin (1541-1612), a Lutheran pastor from Gärtringen (a small town near Herrenberg) and Magdalena Rieger (1540-1580). Wilhelm had a younger brother, Lukas, and a sister.

The Schickards were a well-known Herrenberg family, originally from the German region Siegerland (in region Nordrhein-Westfalen), but had moved south at the beginning of the 16th century. The great-grandfather of Wilhelm — Heinrich Schickard (1464-1540) from Siegen, also known as Heinrich Schickhardt der Ältere or Heinrich der Schnitzer, was a famous woodcarver and sculptor, whose wood-works (stalls from 1517) are still preserved in the church Stiftskirche Herrenberg. He was the founder of the Herrenberg Schickards family, moving in 1503 from Siegen, Siegerland, to Herrenberg. A brother of Lukas Schickard and uncle of Wilhelm is Heinrich Schickard (1558-1635) — one of the most prominent German architects of the Renaissance. The other uncle of Wilhelm is Philipp Schickard (1562-1635), a well-known theologian in his lifetime.

Wilhelm, a precocious child, started his education in 1599 in a Latin school in Herrenberg. After the death of his father Lukas in September 1602, his uncle Philipp, who served as a priest in Güglingen, took care of him, and in 1603 Wilhelm attended a Latin school there. In 1606 another uncle of his, Wilhelm Gmelin, took young Wilhelm to the church school in Bebenhausen Monastery, near Tübingen, where he was a teacher.

Further Education

The school in Bebenhausen was associated with the Protestant theological seminary Tübinger Stift, in Tübingen, so in March 1607 the young Wilhelm entered a bachelor program of the Stift, held in Bebenhausen. In April 1609, he received his bachelor’s degree. In Bebenhausen Wilhelm studied not only languages and theology but also mathematics and astronomy.

In January 1610, Wilhelm went to the Tübinger Stift to study for his master’s degree.

Tübinger Stift is a hall of residence and teaching of the Protestant Church in Württemberg. It was founded in 1536 by Duke Ulrich for Württemberg born students, who want to be ministers or teachers. They received a scholarship that covered boarding, lodging, and further support (students received for their personal needs six guilders per year cash). This was very important for Wilhelm because his family apparently was short of money and could not support him. After the death of his father in 1602, in 1605 his mother Margarethe got married to Bernhard Sick — he was a pastor in Mönsheim, who also died several years later, in 1609.

Besides Schickard, other famous students of Tübinger Stift are Nikodemus Frischlin (1547-1590), a famous humanist, mathematician, and astronomer from the 16th century; the great astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630); the famous poet Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843); the great philosopher Georg Hegel (1770-1831) and others.

After receiving his master’s degree in July 1611, Wilhelm continued studying theology and the Hebrew language in Tübingen until 1614, working at the same time as a private teacher of mathematics and oriental languages; he even worked as a vicar in 1613. In September 1614 he took his last theological examination and started his church service as a Protestant deacon in Nürtingen, a town, located some 30 km north-west of Tübingen.

His Marriage, Religious Duties, and Professorship

On 24 January, 1615, Wilhelm wed Sabine Mack from Kircheim. They were to have 9 children, but (as it was common in these times), only 4 survived by 1632: Ursula Margaretha (born 03.03.1618), Judith (b. 27.09.1620), Theophil (b. 3.11.1625) and Sabina (b. 1628).

Schickard served as a deacon till the summer of 1619. His duties at church left him plenty of time for his studies. He continued his work on ancient languages, and translations, and wrote several treatises. For example, in 1615 he sent Michael Maestlin an extensive manuscript on optics. During this time he developed also his artistic skills, creating several portraits and astronomical tools, and had even a copper press.

In August 1619, he was appointed as a professor of Hebrew at the University of Tübingen, recommended by Herzog Friedrich of Württemberg. The young professor created his own method for presenting material and also taught other ancient languages. Schickard also learned Arabic and Turkish. His Horolgium Hebraeum, a textbook for learning Hebrew in 24 hourly lessons, went through countless editions during the next 2 centuries. Actually, Schickard was a remarkable polyglot. Besides German, Latin, Arabic, Turkish, and some ancient languages like Hebrew, Aramaic, Chaldean, and Syriac, he knew also French, Dutch, etc.

Research and Teaching Methods

His efforts to improve the teaching of his subject show remarkable innovation. He strongly believed that, as the professor, it was part of his job to make it easier for his students to learn Hebrew. One of his inventions to assist his students was the Hebraea Rota. This mechanical device displayed the conjugation of Hebrew verbs by having two rotating discs laid on top of each other, the respective forms of conjugation appearing in the window. Besides Horologium Hebraeum, in 1627 he wrote another textbook— the Hebräischen Trichter, for German students of Hebrew.

An Interest in Astronomy, Mathematics, and Surveying

However, his research was broad and, in addition to Hebrew, included astronomy, mathematics, and surveying. In astronomy, he invented a conic projection for star maps in the Astroscopium. His star maps of 1623 consist of cones cut along the meridian of a solstice with the pole at the center and apex of the cone.

Schickard also made significant advances in map-making, writing a very important treatise in 1629, showing how to produce maps that were far more accurate than those that were currently available. His most famous work on cartography was Kurze Anweisung, wie künstliche Landtafeln auss rechtem Grund zu machen, published in 1629.

In 1631 Schickard was appointed professor of astronomy, mathematics, and geodesy at the University, because he had already significant achievements and publications in these areas, taking the chair from the famous German astronomer and mathematician Michael Maestlin, who died the same year. He lectured on architecture, fortification, and hydraulics. He also undertook land surveying of the duchy of Württemberg, which involved the first use of Willebrord Snell’s triangulation method in geodesic measurements.

As professor of astronomy Schickard lectured on the topic and undertook research into the motion of the moon. He published Ephemeris Lunaris in 1631, which allowed the position of the moon to be determined at any time. We should note that, at a time when the Church was trying to insist that the Earth was at the center of the universe, Schickard was a staunch supporter of the heliocentric system. In 1633 he was appointed dean of the philosophical faculty.

Acquaintance With Johann Kepler

An important role in the life of Schickard was the great astronomer Johann Kepler. After their first meeting in the autumn of 1617 (Kepler was passing through Tübingen on his way to Leonberg, the Württemberg town where his mother had been accused of being a witch), they had a busy correspondence and several other meetings (in 1621 for a week, later on for 3 weeks). Kepler used not only Wilhelm’s talent for mechanics but also his artistic skills. In 1618 Schickard built a tool for comet watching for Kepler. Later on, Schickard took care of Kepler’s son — Ludwig, who was a student in Tübingen.

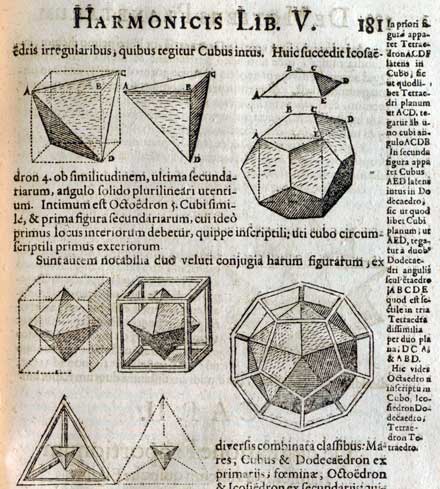

Schickard agreed also to draw and engrave the figures of the second part of the Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae of Kepler on woodblocks, yet Krüger (Kepler’s publisher), always ready to interfere with Kepler’s plans, stipulated that the carving had to be done in Augsburg. Schickard sent thirty-seven woodblocks for books 4 and 5 to Augsburg towards the end of December 1617. Schickard engraved also the figures for the last two books (the carving was done by one of his cousins).

Wilhelm also proposed to Kepler the development of a mechanical means of calculating ephemerides and created the first hand planetarium. Schickard created also, probably by request from Kepler, an original instrument for astronomy calculations (see the photos below). Kepler showed his gratitude, sending him several of his works, two of which are still preserved in the University Library in Tübingen.

Flight to Austria

In 1631 the life of Schickard and his family was under threat of the battles of the Thirty Years’ War, which approached Tübingen. Before the Battle of Tübingen in 1631, he fled with the entire family to Austria and returned after several weeks. In 1632 the family again fled to Austria. In June 1634, hoping for quieter times, he bought a new home in Tübingen, suitable for astronomical observations. His hopes were vain although. After the battle of Nördlingen in August 1634 the Catholic forces occupied Württemberg, bringing violence, famine, and plague with them. Schickard buried his most important notes and manuscripts, in order to save them from plunder. These partly survived, but Schickard’s family did not. In September 1634, in sacking Herrenberg, the soldiers from the Catholic forces beat Schickard’s mother — Margarethe, who died a lingering death of her wounds. In the next January of 1635, his uncle, the architect Heinrich Schickard, was killed by soldiers.

At the end of 1634 Schickard’s eldest daughter, Ursula Margaretha, a girl of unusual intellectual attainment and promise, died from plague. Then his wife Sabine and the two youngest daughters, Judith and Sabina, two servants, and a student, who lived in his house died. Schickard survived this outbreak, but the following summer the plague returned, taking with it in September his sister, who was living in his house. Schickard and his only surviving child — 9-year-old son Theophilus, fled to the village Dußlingen, near Tübingen, having the intention to emigrate to Geneva, Switzerland. However on 4 October 1635, fearing that his house and especially his library would be plundered, he returned to Tübingen. On 18 October he became sick of plague and died on 23 October 1635. His little son followed him after a day.

Besides Kepler, Schickard also corresponded with some other famous scientists of his time — mathematician Ismael Boulliau (1605-1694), philosophers Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655) and Hugo Grotius (1583-1645), astronomers Johann Brengger, Nicolas-Claude de Peiresc (1580-1637) and John Bainbridge (1582-1643), and many others.

A Remarkable Life

Wilhelm Schickard was one of the most reputable scientists in Germany of his time. The opinions of this universal genius from his contemporaries are — the best astronomer in Germany after Kepler’s death (Bernegger), the foremost Hebraist after the death of the elder Buxtorf (Grotius), one of the great geniuses of the century (Peiresc). However, like many other geniuses with wide interests, Schickard was in danger of stretching himself too thin. He succeeded in finishing only a small part of his projects and books, being struck down in his prime.

Books, written by Wilhelm Schickard:

- Cometenbeschreibung, Handschrift, 1619

- Hebräisches Rad, 1621

- Astroscopium, 1623

- Horologium Hebraeum, 1623

- Lichtkugel, 1624

- Der Hebräische Trichter, 1627

- Kurze Anweisung, wie künstliche Landtafeln aus rechtem Grund zu machen, 1629

- Ephemeris Lunaris, 1631.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©"Wilhelm Schickard machine replica 1623" by teclasorg is licensed under BY 2.0. – License / Original