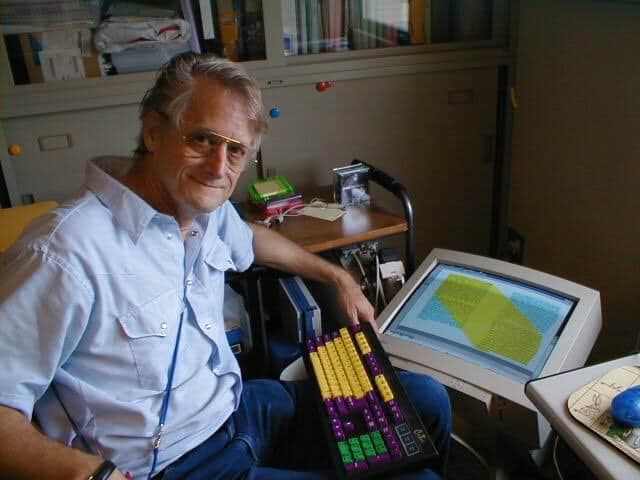

Who Is Ted Nelson?

Born in 1937, Theodor Holm Nelson is an American philosopher, computer scientist, and sociologist. He specializes in the fields of information technology and cyber philosophy. Many of his ideas were responsible for helping create the conceptual structure of the modern internet.

Early life

Nelson gives the credit to his parents for much of his creativity and the opportunities that helped jump-start many of his ideas. His father was a television director who won an Emmy award, and his mother won an Oscar as an actress.

Quick Facts

- Full Name

- Theodor Holm Nelson

- Birth

- June 17, 1937

- Net Worth

- $900,000

- Awards

- Yuri Rubinsky Memorial Award

- Officier des Arts et Lettres

- Children

- NA

- Nationality

- American

- Place of Birth

- Chicago, IL

- Fields of Expertise

- [“Philosophy”,”Information Technology”,”Sociology”]

- Institutions

- Swarthmore College, University of Chicago, Harvard University

- Contributions

- Hypertext, hypermedia, intertwingularity, transclusion, virtuality

As a young boy, Nelson would often accompany his father to the television sets of whichever CBS or NBC show his father was directing at the time. He used this experience to direct various short films later in life, starting with a 30-minute film he made about the meaning of life while studying for his bachelor’s degree in philosophy at Swarthmore College.

Nelson went on to perform graduate studies at the University of Chicago and Harvard University, where he earned a master’s degree in sociology. In Harvard, upon seeing the array of computer screens in the computer lab, it first occurred to him that, instead of the text-based output of the time, the monitors could be used for much more than just imitating paper.

In the early 1960s, Nelson wrote to John Lilly, a dolphin researcher, with a few ideas he had come up with for studying dolphin language. Lilly was impressed and hired him. Nelson spent a year working with dolphins at Lilly’s Communication Research Lab in Miami, analyzing dolphin behavior and making movies about dolphin activity before moving on to his career in information technology.

Career

The Itty Bitty Machine Company

In 1977, Nelson opened a cozy retail store in Evanston, Illinois, that sold computers and their components. He called it the Itty Bitty Machine Company (IBM, but not that one). It became one of the only computer stores that sold Steve Jobs’ first Apple I machine.

Xanadu Operating Company

In 1979, Nelson decided to try to realize some ideas he had been working on about a new conceptual structure for software. He called the software Xanadu, which is a reference to a utopic city from “Kubla Khan,” a poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Xanadu began as Nelson’s quest for greater personal organization. At the time, what Nelson calls his “hummingbird mind” was buzzing with information technology insights, movie scripts, philosophic musings, etc. The problem was that he couldn’t keep track of all the open threads.

He imagined a computer program that would help him organize all the branches of his various idea trees in a nonlinear way that was much closer to the way his brain actually worked than the linear style of paper notes. This interconnected style of organizing ideas Nelson called “hypertext.”

What Did Ted Nelson Invent?

Hypertext and Hypermedia

Nelson first came up with the idea of hypertext and hypermedia in 1962. He had finally found what he thought was a way to make computers and their screens live up to their full potential as more than just digital paper.

The idea was to create a worldwide “docuverse” where all information was connected contextually by links. Rather than consuming information sequentially one page at a time, anyone would be able to immediately access any information from anywhere else via these links.

This would be better than text. It would be hypertext.

Before this idea, the internet was organized into hierarchical layers of folders, much like your computer. To find the information you wanted, you had to know which folder it was in. Nelson’s idea would avoid what he called the “hierarchical hell” and bring universal net neutrality by letting pages link to each other wherever they were located.

Xanadu and Simplified Hypertext

Nelson dedicated most of his adult life to designing Xanadu. It represented to him, and still represents, the right way to implement hypertext.

As a would-be global library of indexed information, Xanadu began with these primary goals:

- Related documents should be linked together with two-way links

- Older versions of pages should be stored and kept track of rather than deleted

- Use of copyrighted information should be tracked and automatically reimbursed

- Anyone should be able to annotate any information as easily as writing in the margins of a book

- Any page with a quote should be displayed alongside the page with the original quote in context

At the start of the project, Nelson believed it would take around two years to finish Xanadu, after which he’d retire from information technology and make films. In the 1980s, however, Autodesk, the company that had been backing his project financially, ran into some problems. Nelson’s progress ground almost to a halt.

In 1991, a software engineer named Tim Berners-Lee was working at CERN, a particle physics laboratory in Europe. Berners-Lee needed a way to let scientists using incompatible operating systems share their reports.

He started with Nelson’s hypertext idea and simplified it drastically to come up with what he called Hypertext Markup Language (HTML). Berners-Lee wasn’t trying to permanently redesign humanity’s cyber image; he just wanted his team to be able to communicate better. HTML went viral and soon became the backbone of what we now call the “World Wide Web” (WWW).

The WWW design didn’t do away with the hierarchy format like Nelson wanted. It just spun a web of linked connections that sat on top of the existing hierarchy of folders.

Nelson wasn’t happy with this simplification of his idea. To this day, he’s still working on his system of information technology based on true net neutrality rather than a thinly veiled hierarchy.

Cyber Philosophy: Intertwingularity, Transclusion and Virtuality

Nelson’s invention of hypertext and hypermedia is based on a philosophy he came up with called “intertwingularity.” He believes ideas are naturally “intertwingled.” Related topics bleed into each other, creating webs of connections rather than linear narratives. Nelson is convinced the concept of intertwingularity makes paper-based structures like the hierarchy of folders obsolete.

In Nelson’s version of hypertext, all links would go two ways. When you click on a link, instead of a new page replacing the one you’re on, the linked sources would appear beside, behind, and around your page in an amorphous multi-dimensional idea-space. You’d be able to see all the pages linking to the current document with every idea in its original context alongside its new appearance. You’d also be able to add your own ideas as annotated third-party links connected to the source.

To Nelson, intertwingularity means that paper-based structures are prisons, and footnotes in books are evidence that ideas want to escape. Even in its simplified version, this idea of connected links, which we’ve all come to expect from the internet, was a completely alien concept only a couple of decades ago.

Another of Nelson’s philosophies underlying his concept of hypertext is a technique he named “transclusion.” A similar concept we use in today’s web is embedding. HTML allows us to embed images or videos from other websites into our own pages. Transclusion would allow us to embed not only media but any content, including single documents, short text quotes, and even entire websites.

In a hypothetical completed Xanadu system, any time you cited any kind of source, the content would automatically link out to its original location instead of creating a digital copy. A transclusion-based internet would mean zero redundancy. Every piece of content would only exist in one place online, and every usage would link directly to the original. Unfortunately, this kind of library is extremely difficult to program in the real world.

The final important concept backing Nelson’s hypertext is the idea of virtuality. Virtuality is an old word that contrasts the reality of a thing with how it seems or feels to us. To Nelson, virtuality divides into two subsections: the conceptual structure and the feel.

Let’s use movies as an example. The feel refers to the emotions it incites in us. The conceptual structure involves how the movie moves through its narrative, how many acts it has, and the mechanics of both the journey and the destination of the story. The reality of a movie, on the other hand, jumps out of the plot to the behind-the-scenes grit of how each shot was designed, filmed, and edited.

In the software world, the reality is the actual code. The conceptual structure refers to the constructs the programmers had in mind when designing the software, ideas like the page model of websites, the web model of the internet, and the layer model of machine learning algorithms. The feel involves final design touches like color palettes, word choices, and typography.

Ted Nelson: Marriage and Personal Life

Net Worth

Ted Nelson’s net worth is estimated to be around $900,000.

First Marriage

Ted Nelson’s first wife was Marlene Mallicoat, a computer consultant and software designer from Oregon. They spent 23 years together, traveling among various universities, then residing in England and Japan for around five years each.

Tragedy

After a prolonged illness, Marlene Mallicoat died on May 22, 2015.

Second Marriage

In 2010, Nelson’s long-time friend, Lauren Sarno, became his second wife. They had met in a computer club almost 50 years earlier. Sarno had also been a lifelong friend of Marlene Mallicoat, Nelson’s first wife.

Sarno is a journalist and editor specializing in technology. She won a Grammy for her performance of Mahler’s Third in a symphony chorus and also holds a third-degree black belt from the Bujinkan martial arts organization in Japan.

Ted Nelson: Awards and Achievements

Yuri Rubinsky Memorial Award

In 1998, at the International World Wide Web Conference held in Australia, Nelson was given the Yuri Rubinsky Memorial Award for his lifetime of contributions to information technology and infrastructure.

Officier des Arts et Lettres

In 2001, he was knighted by the French government to become an official member of France’s “Officier des Arts et Lettres.”

Ted Nelson: Published Works and Books

Computer Lib / Dream Machines

In 1974, Nelson self-published his first nonfiction book “Computer Lib / Dream Machines.” The book was the first to lay out some of the founding arguments of net neutrality. It insists that computer technology must belong to everyone, not only the interests of big businesses.

It impacted enormously the budding world of information technology, becoming a sort of underground holy book for programmers and hackers. It also helped elevate his net worth, enabling him to later invest money and time into his favorite ideas.

The Home Computer Revolution

In 1977, Nelson published “The Home Computer Revolution,” which is still considered surprisingly prescient for its day. Among other insights, the book predicted that software and screens would slowly eat the world, replacing most other appliances in the kitchen, office, school, automobile, bedroom, etc.

Literary Machines

Nelson released “Literary Machines” in 1980 as an in-depth report on the status, progress, and future of Project Xanadu.

The Future of Information

In 1997, Nelson published a compilation of his principal ideas on computer science called “The Future of Information.” It covered much of his philosophy of information technology and the conceptual structure of software.

Possiplex

Nelson’s latest book was an autobiography released in 2011 called “Possiplex.”

Ted Nelson: Quotes

- “Most people are fools, most authority is malignant, God does not exist and everything is wrong.”

- “The good news about computers is that they do what you tell them to do. The bad news is that they do what you tell them to do.”

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Belinda Barnet, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons – License / Original