Who was Paul Otlet?

Paul Marie Ghislain Otlet was a Belgian who was a pioneer in the field of information science and is considered the father of Google. Throughout his life, he worked as an author, lawyer, entrepreneur, and peace activist. He was perhaps most of all a visionary, and his work in documentation was an inspiration for what later became the Internet.

In the 1890s, he took on the overwhelming task of attempting to collect and organize all the knowledge in the world. In 1895 Otlet, along with lawyer Henri La Fontaine, established what was officially called, the International Institute of Bibliography. This institute would be responsible for developing and distributing a universal classification and catalog system.

Quick Facts

- Full Name

- Paul Marie Ghislain Otlet

- Birth

- August 23, 1868

- Death

- December 10, 1944

- Children

- two sons

- Nationality

- Belgian

- Place of Birth

- Belgium

- Fields of Expertise

- [“Law”]

- Institutions

- Otlet co-founded the Institute International de Bibliographie.

- Contributions

- Organizing information and providing inspiration for the Internet.

This was an attempt to control and organize the entire spectrum of all known knowledge. Near the end of his career, he had put together his ideas into two books. Traité de documentation, which was published in 1934, and Essai d’universalisme, which came out in 1935.

Throughout history, other individuals also tried to record and make accessible vast amounts of information. One well-known example was the Library of Alexandria. This was an impressive repository of information and knowledge built in Alexandria, Egypt by Ptolemy I around 300 BC. It was later destroyed somewhere between 48 BC and 642 AD, supposedly by fire. Historians speculate that it held 700,000 papyrus scrolls, which is equivalent to 100,000 books.

Paul Otlet’s Early Life

Paul Otlet was born in Brussels, on August 23, 1868. He was the oldest child of Edouard and Maria Otlet. His father was a successful businessman and the family was relatively wealthy. His mother died when Paul was only three. His father educated him with tutors until he was 11 instead of sending him to school. As a child, he, therefore, had few friends, but he spent much of his time reading and developed a love for books.

By age 11, Paul began receiving a regular education, which included attending a Jesuit school in Paris. After the family returned to Brussels his father remarried and Paul eventually had five new siblings in addition to his brother. They spent time traveling to places such as France, Italy, and Russia. Otlet later attended both the Catholic University of Leuven and the Free University of Brussels. He eventually earned a law degree.

On December 9, 1890, Otlet married Fernande Gloner, his step-cousin. He began his career working as a law clerk for Edmond Picard. Not long after starting his legal career, Otlet took an interest in bibliography. The first work he ever published came out in 1892 and was an essay titled, Something about Bibliography. In this essay, Otlet wrote that books were inadequate to store information and that a better storage system would include cards containing specific chunks of information. This type of information could more easily be accessed.

Otlet’s Early Career and Professional Life

Paul Otlet worked as a lawyer early in his career. During this time he wrote about the increasing abundance of written material. In 1893, Otlet wrote an essay that discussed his concern regarding the extensive proliferation of articles, periodicals, and books. He argued that the problem of quality instead of quantity was a major issue that should be dealt with. He worried that it would be difficult for anyone to make sense of all the overabundance of unorganized material available.

Paul Otlet went on to become a prime figure in the development of modern documentation. He worked for decades with the technical and organizational aspects of making recorded knowledge available in an easily accessible filing system. He spent much of his life designing, developing, and initiating creative solutions at his Institute in Brussels.

Later Career and Professional Life

Paul Otlet was also known for his peace activism and idealistic thinking. He promoted political ideas that were part of the League of Nations and the International Institute for Intellectual Cooperation. In 1895, Otlet and his colleague Henri LaFontaine co-founded the International Institute of Bibliography. This organization was to promote the efficient organization and use of knowledge.

Otlet set up a service in 1896 to answer questions by mail. For a fee, requesters were sent copies of index cards that related to their questions. This service was called an “analog search engine” by scholar Alex Wright. By 1912, there were over 1500 queries each year for this service.

Otlet is ultimately known for the Mundaneum, which was an institution with the goal of gathering all the world’s knowledge into an intricate filing system. As this information was gathered, it would be classified into what was the Universal Decimal Classification. Otlet and La Fontaine began this classification system in 1904. The initial publication was completed in 1907. The Mundaneum is a milestone in technology and what ultimately becomes our modern system of data collection and management. It also helped cement Otlet’s reputation as the father of Google.

Otlet was working with LaFontaine when they published the Universal Decimal Classification (UDC) in 1904. This system divided knowledge into nine categories. They had a tenth category that was to be kept for any expansion. There are categories such as Literature, Mathematics, and Natural Sciences. Each of these is further broken down into thousands of potential subdivisions. The UDC is in use in at least 130 countries and has been translated into 50 languages.

In 1907 Otlet and LaFontaine created the Central Office of International Associations. This was renamed the Union of International Associations in 1910. This association is still located in Brussels.

Henri LaFontaine won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1913 regarding the global diffusion of information and new kinds of ways to organize it. This began in 1910 when Otlet and LaFontaine initially envisioned what was called a “city of knowledge.” Otlet had originally called this Palais Mondial, or what is also called World Palace. The World Palace would consist of organizations such as a World Museum, a World University, and a World Library. These would all serve in conjunction as a central repository for all the world’s information.

It was eventually named the Mundaneum. This grand scheme would include the ability to store and access massive amounts of data. During this time Melvil Dewey published what would become known as the Dewey Decimal System. This system used 3 by 5 paper index cards. Otlet incorporated the card system as part of his plan to organize and manage information.

Otlet, along with chemist Robert Goldschmidt, suggested using microfiche as a format for a micro-photographic book in 1910. They were hoping to create micro-photographic books that would be part of a portable library.

What Did Paul Otlet Invent?

Invention 1

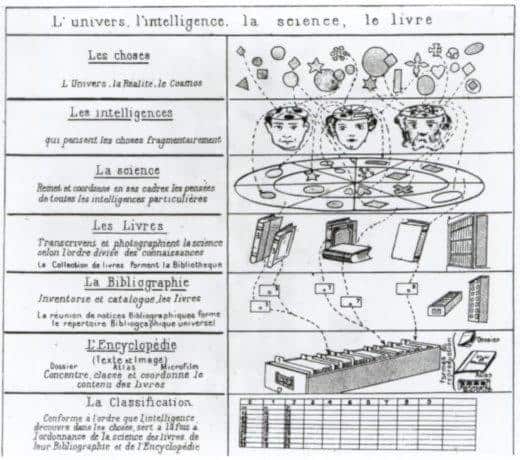

Paul Otlet is famous for Traité de Documentation. In this, Otlet speculated about possibly communicating online with text-voice conversion. He envisioned what would be needed at computer workstations, although he did not use this exact terminology. Otlet mentions inventions like machine translations for information retrieval and processing. The following is an outline Otlet provided regarding a personal information filing system.

We should have a complex of associated machines which would achieve the following operations simultaneously or sequentially:

1. Conversion of sound into text;

2. Copying that text as many times as is useful;

3. Setting up documents in such a way that each datum has its own identity and its relationship with all the others in the group and to which it can be re-united as needed;

4. Assignment of a classification code to each datum and then rearrangement of the parts of the document to correspond with the classification codes;

5. Automatic classification and storage of these documents;

6. Automatic retrieval of these documents for consultation and for delivery either for inspection or to a machine for making additional notes;

7. Mechanized manipulation at the will of all the recorded data to derive new combinations of facts, new relationships between ideas, new operations using symbols. The machinery which would achieve these seven requirements would be a veritable mechanical and collective brain.

In Traité de Documentation, Otlet also predicted that eventually books and other types of information sources would allow individuals to feel, taste, and smell the information. He called these sense-perception documents.

Invention 2

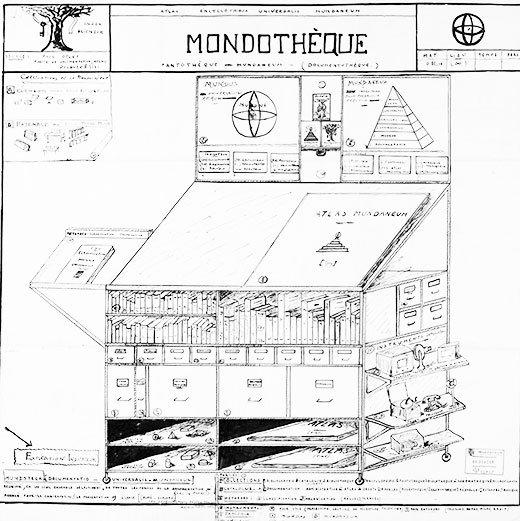

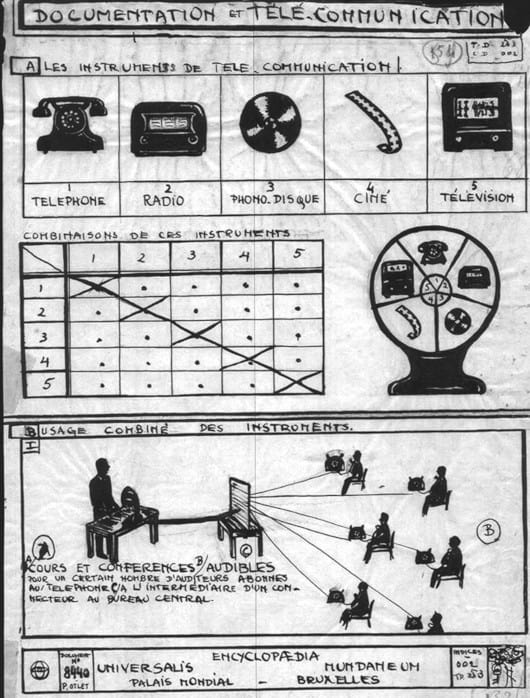

In his l’Encyclopedia Universalis Mundaneum from 1936, Otlet conceptualized and designed a large network, comprised of data centers, called Mundaneum, and multimedia offices, called Mondothèque (see the lower image).

Otlet envisioned Mundaneums in various cities all over the world and a large hierarchical network of local, regional, and national centers of knowledge production: Species Mundaneum. The Mondothèque was one link in this network. Otlet designed the Mondothèque as a workstation to be used at home to engage people in the production and dissemination of knowledge. It contained reference works, catalogs, multimedia substitutes for traditional books such as microfilm, TV, and radio, and finally a new form of an encyclopedia, the Encyclopedia Universalis Mundaneum, comprising reproducible “atlases” involving charts, posters, and other illustrative materials. As a base instrument for documentation and communication of Mundaneum, Otlet provided the known media, like telephone, radio, audio disk, cinema, and television (see the lower image).

The Mondotheque was thought by Paul Otlet to be a piece of furniture that everyone would have at home, to encourage access but also the production of new knowledge. Made of wood, it combines essential books, atlas boards in the form of visual encyclopedias, small objects, the Universal Bibliographic Directory and its bibliographic records, microfilms, etc. On the sidewalls of the Mondothèque, we can observe various media of the period represented.

After the Mundaneum was created it eventually became an archive with over 12 million documents and index cards. Many now consider this achievement the forerunner of the Internet. The Mundaneum was originally kept in Brussels at the Palais du Cinquantenaire. It was later renamed Palais Mondial before the name Mundaneum was officially used.

In 1929, Otlet commissioned an architect to develop a type of Mundaneum project. This was to be built in Switzerland. This project, however, never came to fruition and triggered what was known as the Mundaneum Affair. This was a supposed argument between the architect, Le Corbusier, and another architect and critic, Karel Teighe. Otto Neurath started the Mundaneum Institute as part of The Hague in 1933 after gaining permission from Otlet.

Before computer science and long before the World Wide Web was in use, Paul Otlet pursued the lofty goal of organizing all the information in the world. He spent nearly fifty years indexing and cataloging all significant information and facts. He built an extensive bibliography of approximately 15 million books, newspapers, magazines, photographs, and other types of media. His goal was not about ownership but universal sharing and access.

Paul Otlet also spent much of his life attempting to establish peaceful interactions between nations. He believed that democratizing information through a global network would help foster goodwill and peace. Otlet’s work has inspired many in the field of science, and in particular those who went on to devise the Internet.

Paul Otlet: Marriage, Children, and Personal Life

Net Worth

While Paul Otlet’s exact financial worth throughout his life is unknown, he was born into a wealthy family, enjoyed private tutors, and traveled rather extensively. Later in Otlet’s life, however, it is known that some of his businesses struggled. Due to the outbreak of World War I Otlet was struggling to secure funding for his professional endeavors.

Marriage

Otlet married Fernande Gloner on December 9, 1890.

Children

Otlet and his wife had two children, sons named Marcel and Jean.

Paul Otlet’s Published Works and Books

Book 1

Paul Otlet published Traité de documentation in 1934.

By the time Traité de documentation was published in 1934, Otlet was proposing remote access to all types of data. Ever the entrepreneur, he hoped that workstations would have a link to the Mundaneum via telephone, or television technology, which was in its early stages at this time. Anyone could call in and ask a question and the answer would ultimately come through on a personal screen. Otlet even was hoping for users to share social interactions along with data.

Book 2

Otlet’s second book Monde: Essai d’universalisme was published in 1935.

In this publication, Otlet described an information network that would provide access to all the currently known information. Otlet’s vision ultimately became the basis for the modern Internet.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Paul Otlet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – License / Original