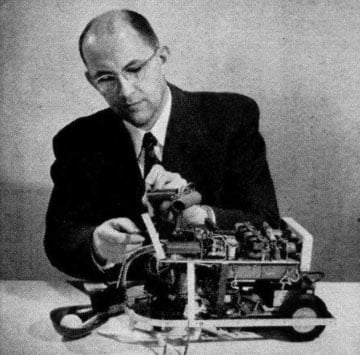

Edmund Callis Berkeley (the image is property of the University of Minnesota)

Early Life and Education

Edmund Callis Berkeley was born in Manhattan, New York, on 22 February 1909, to William and Ellen Berkeley.

His primary school was St. Bernard’s School for Boys, an elite, private all-male elementary school in Manhattan, which Edmund attended from 1918 till 1923. After graduating he continued at Phillips Exeter Academy, a distinguished college preparatory school for boys in New Hampshire, where he was the youngest student, and graduated first in his class. There his teachers recognized his exceptional mathematical talent and directed him for individual instruction. At this time Edmund was seen as an intelligent but socially awkward boy, who did not fit in with the sons of other elite families, who made up the majority of students, some were even 5-10 years older than him.

First Job and College Education

Edmund was only 16 when he graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy, so his parents decided to give him a break before college. For a year he lived in his family home near Columbia University, working as an instructor at St. Bernard’s School.

The Main building, Gymnasium, and Abbot Hall of Phillips Exeter Academy in the 1920s

In 1926, Edmund entered Harvard College and graduated summa cum laude in Mathematics and Logic in June 1930. His dream since childhood was to become a mining engineer, however, while in Harvard he changed his mind. He chose to pursue a career as a creative mathematician. For him, the mathematics was not only rigorous reasoning, it was a magic, a wizardry of Arabia.

Early Career

During the time of his graduation in 1930, the Great Depression was setting in deeper, and his parents advised him to be practical and to seek a career in business, instead of creative mathematics. As a result, Edmund pursued a career as an actuarial clerk in Mutual Life Insurance of New York.

In June 1934 he married Ruth Pirkle (1899-1991) of Cummings, Georgia, a 35-year-old Ph.D. in biology and teacher at Hunter College in Manhattan. At the same time, he inherited over 8000 USD from his aunt. Thus the couple decided to go for three and half months honeymoon tour in Europe. They visited ten countries, including Italy, Greece, Turkey, Norway, and even the Soviet Union.

Upon his return in the autumn of 1934, Berkeley took a position in the actuarial department of Prudential Insurance of America in New Jersey, where he eventually became chief research consultant. In 1937 he published an article in the magazine The Record of the American Institute of Actuaries, in which he argued for the using of symbolic logic for resolving insurance problems like analyzing risk and developing rules for writing policies.

Military Career

During World War II Berkeley was given a leave for military duty. In 1942 he enlisted in the United States Navy as a Naval Reserve officer for three and a half years. Initially, he was an Inspector of supply, but later he was reassigned under Howard Aiken at the Harvard Computation Laboratory and was assigned to help run the Mark I computer. The work with Mark I was a really stimulating experience for Berkeley.

Post Military Career

In 1946 Berkeley returned to his work at Prudential as Senior Methods Analyst, later advancing to Chief Research Consultant. He was assigned a very interesting task — to determine how the company could use the new automatic electronic equipment for data processing. However, in 1948 a change in the company management resulted in an extensive reduction of his assignment, later other differences cropped up, especially regarding the book he was writing.

Creating Berkley Enterprises

In 1948 he decided to become a self-employed professional by being a lecturer, a consulting actuary, a publisher, and a developer of computers. His newly-founded company, Berkeley Enterprises, was particularly interested in symbolic logic, computers, robots, mathematics, operations research, language, explanation

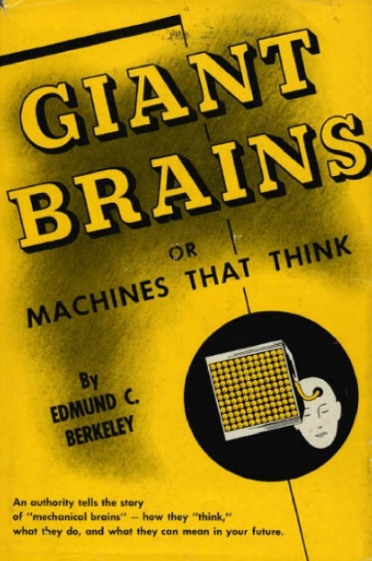

In 1949, Berkeley wrote one of the first books on electronic computers for a general audience, which made him famous — Giant Brains, or Machines That Think, in which he described the principles behind computers, and then gave a technical but accessible survey of the most prominent examples of the time, including machines from MIT, Harvard, the Moore School, Bell Laboratories, and others. In this book, Berkeley envisioned that computers would be applied not only to mathematical and computational problems, but also to a wide range of other problems, like finding information in a library, typing text from voice, translating languages, and controlling other machines.

Edmund and Ruth Berkeley divorced in 1948, and in 1949 he married Susan Slocum Wallace (16 Aug. 1911—18 Feb. 2001) from Newtonville, Massachusetts, adopting her three children into his family.

In the 1950s Berkeley devoted much effort to developing robots and making them available to anyone, who could pay a small sum for a mail-order kit (see the Electric Brain Simon of Berkeley). In the October 1950 issue of the journal Radio Electronics was published an article, which was an introduction to Simon and relay logic. In the next issue 12 articles were published, relating plans on how to build a computer, as well as a general description of state-of-the-art computers.

In 1950 Berkeley founded, published, and edited a journal, Computers and Automation, thought to be the first computer magazine.

Death

Edmund Berkeley was a genius, whose eccentricities had become proverbial even before his talents were widely recognized. He died in Boston on 7 March 1988 and was buried in Newton Cemetery, Newton, Massachusetts. He was survived by his wife, Susan, two sons, a daughter, and a granddaughter.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Unknown author / public domain