James White

Much of the scarce information, available about the life of James White, a civil engineer and author of the remarkable book A New Century of Inventions, comes from biographical statements in the above-mentioned book.

James White was born in 1762 in Cirencester, Gloucestershire (150 km northwest of London), at that time a thriving market town, at the center of a network of turnpike roads with easy access to markets for its produce of grain and wool. Interestingly, no record of his birth is to be found in the Church Baptismal Register there, so his parents may have been nonconformists.

White’s father gave free rein to his son’s early predilection for mechanics as is illustrated by the fact that when the boy was only about eight years of age and still at school he invented quite an ingenious mouse trap. As James White says:

Should any reader then enquire what were my first avocations? The answer would be, I was (in imagination) a Millwright, whose Water-wheels were composed of Matches. Or a Woodman, converting my chairs into Faggots, and presenting them exultingly to my Parents: (who doubtless caressed the workman more cordially than they approved the work.) Or I was a Stone-digger, presuming to direct my friend the Quarry-man, where to bore his Rocks for blasting. Or a Coach-maker, building Phaetons with veneer stripped from the furniture, and hanging them on springs of Whalebone, borrowed from the hoops of my Grandmother. At another time, I was a Ship Builder, constructing Boats, the sails of which were set to a side-wind by the vane at the mast head; so as to impel the vessel in a given direction, across a given Puddle, without a steersman. In fine, I was a Joiner, making, with one tool, a plane of most diminutive size, the [relative] perfection of which obtained me from my Father’s Carpenter a profusion of tools, and dubbed me an artist, wherever his influence extended. By means like these I became a tolerable workman in all the mechanical branches, long before the age at which boys are apprenticed to any: not knowing till afterwards, that my good and provident Parent had engaged all his tradesmen to let me work at their respective trades, whenever the more regular engagements of school permitted.

Before I open the list of my intended descriptions, I would crave permission to exhibit two more of the productions of my earliest thought—namely, an Instrument for taking Rats, and a Mouse Trap: subjects with which, fifty years ago, I was vastly taken; but for the appearance of which, here, I would apologize in form, did I not hope the considerations above adduced would justify this short digression. If more apology were needful… Emerson himself describes a Rat-trap: and moreover, defies criticism, in a strain I should be sorry to imitate: my chief desire being to instruct at all events, and to please if I can: without, however, daring to at tempt the elegant PROBLEM, stated and resolved in the same words—”Omne tulit punctum, qui miscuitutile dulci.”

We know nothing of White’s education, but he obviously was apprenticed to several trades, because he mentioned, that my good and provident Parent had engaged all his tradesmen to let me work at their respective trades

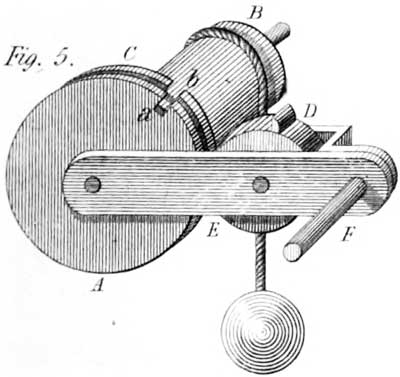

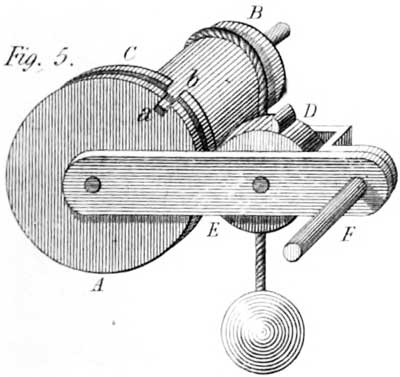

White says that he brought out one of his first inventions he carried into real practice on coming to manhood about 1782, at the request of the late Doctor Bliss, of Paddington. It was a perpetual wedge machine (first constructed as a crane, see the nearby drawing from the book). This was a concentric wheel and axle, the wheel having 100 teeth and the axle one tooth less, thus obtaining a great advantage.

In 1788, giving his address at Holborn London, White took out a British patent No. 1650, for a number of mechanical devices, not all original, e.g. the Chinese windlass is one of them.

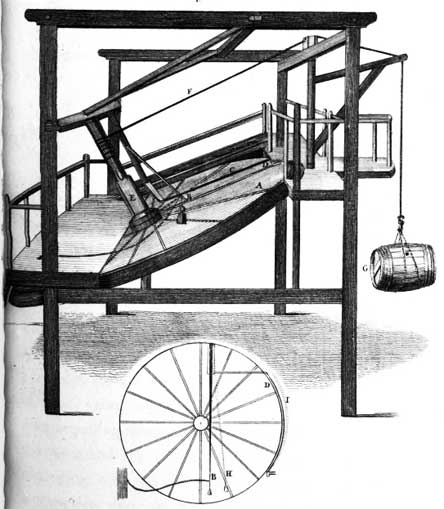

In 1792 White modified the inclined disc treadmill-driven crane for wharfs (see the image below) by refinement of having compartments situated on the disc at a leverage proportional to the weight o be lifted. He submitted a model of the crane to the Society of Arts and was rewarded by a premium of 40 guineas or a gold medal.

White’s treadmill-driven crane for wharves from 1792

At the end of 1792, White departed to Paris, France, where he remained for more than 20 years, making many inventions and starting several business affairs, although not very successful.

First, he claimed the invention of the micrometer, based on the differential movement. In 1795 White obtained another patent, this time for a Serpentine boat, i.e. a string of barges, articulated together to reduce traction and for use in restricted waterways, such as canals. In December 1795 he made an association with the Parisian carpenter Jean-Baptiste Decoeur, and invented a “machine à l’instar des lieux à l’anglaise”, patented in 1797. In 1796 White and Decoeur bought a mill at Charenton.

In 1801 we found James White living at rue de Popincourt, 47, Paris, and working in association with the immigrant Austrian entrepreneur Simon-Thaddée Pobecheim, who established a small cotton mill in the attic of the church Notre-Dame des Blancs-Manteaux. White earned 5% on the profits of the company in exchange for “his talents, processes and industry in mechanics”. In 1803 White and Pobecheim decided to transfer the company to a former grain mill in Baulne, near Ferté-Alais. In 1804, they take a fifteen-year patent for a “un système préparatoire des matières filamenteuses”, which they perfected several times later, and continued their teamwork until 1807.

At the second Exposition des produits de l’industrie française in 1801, White demonstrated his hypo-cycloidal mechanism, based on the property formulated by the French scientist Philippe de La Hire in 1666, that a point on the circumference of a wheel rolling inside one twice its diameter will describe a straight line. This invention was awarded with a renumerating medal from Napoleon Bonaparte. At the same exposition, White presented also a dynamometre.

In the early 1800s, White invented and in 1808 patented single and double helical spur gearing, perhaps the invention on which he seems to have placed most store. He invented also a horizontal water wheel, which was in effect a radial outward-flow turbine.

Another patent, that White took during his stay in France (in 1811) is seemingly of great importance — for an automatic nail-making machine. This was the first machine for making nails from wire, and later a considerable manufacture sprang up in France. White has also been credited also being the first to bring out, in 1811, shears for cutting sheet iron in circular shape.

After breaking his agreement with Pobecheim in 1807, White moved to rue Saint-Sébastien in Paris, and from 1809 he lived in Hotel Bretonvilliers, Ile de St. Louis (see the lower painting from 1757), and was engaged in spinning wool mechanics, velvet weaving and nail making.

Hotel Bretonvilliers, Ile de St. Louis, Paris, in 1757

James White returned to England in February 1815, probably because of the termination of the war by the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo. He settled in Manchester presumably because it was one of the foremost world centers of mechanical engineering, and in December 1815, he presented to the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society the paper On a new system of cog or toothed wheels

White states that “…in 1817 I was employed by Matthew Corbett, one of the proprietors of a factory at the Pin Mill, Ancoats, to erect a number of my wheels,” but owing to the defective lining of the shafting due to overloaded floors, the gears got out of mesh and was scraped out. Later White devised a milling machine to cut the gears by milling cutters.

In 1820 White obtained a British patent No. 4485 for preparation and spinning of textiles

In the 1820s White’s health appears to have been indifferent (in the book he mentions his declining health and approaching mortality), that’s why he decided to leave behind him an account of his inventions and wrote his interesting book New Century of Inventions in 1822. It was obviously a work of some importance, indicated by the names of eminent engineers, who subscribed to it, like Charles Babbage (the creator of Differential Engine and Analytical Engine), Bryan Donkin, Jacob Perkins, William Fairbairn, and others. Further, the book ran to a second edition.

James White died on 17 December 1825, aged 63, in Manchester. He was described in his obituary notice as a civil engineer and author of the New Century of Inventions.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Unknown author / public domain