Key Points About the Tate-Layton Machine

- The Tate-Layton machine was largely based on the work of Thomas de Colmar and other 19th-century arithmometers.

- Charles and Edwin Layton, founders of C. & E. Layton, were originally publishers.

- The design was largely unchanged from the 1883 version to the end of production in 1910.

Tate-Layton Machine History

The first English stepped drum machine (Thomas de Colmar-type arithmometer) was devised in the early 1880s by Samuel Tate (1840-1917), an ironworker and mechanical engineer from Sedgley, Staffordshire. Tate made some improvements in the construction of Colmar’s device and patented his improvements. In 1883, the brothers Charles and Edwin James Layton, booksellers and authors of insurance books exhibited the first arithmometer as the agents of Tate. They soon afterward acquired the patents, arranging a manufacturing workshop on Farrington Road in London to create C. & E. Layton.

Tate-Layton’s machines are generally considered to be the heaviest duty and best made of all of the late 19th-century arithmometers. They were primarily manufactured for use by the insurance industry. Production of the device by C. & E. Layton continued until 1914.

Quick Facts

- Created

- 1883. First commercially sold in 1910

- Creator (person)

- Samuel Tate, Charles Layton, Edwin James Layton

- Original Use

- Performing calculations, primarily in the insurance industry

- Cost

- N/A

Tate-Layton Machine: How It Worked

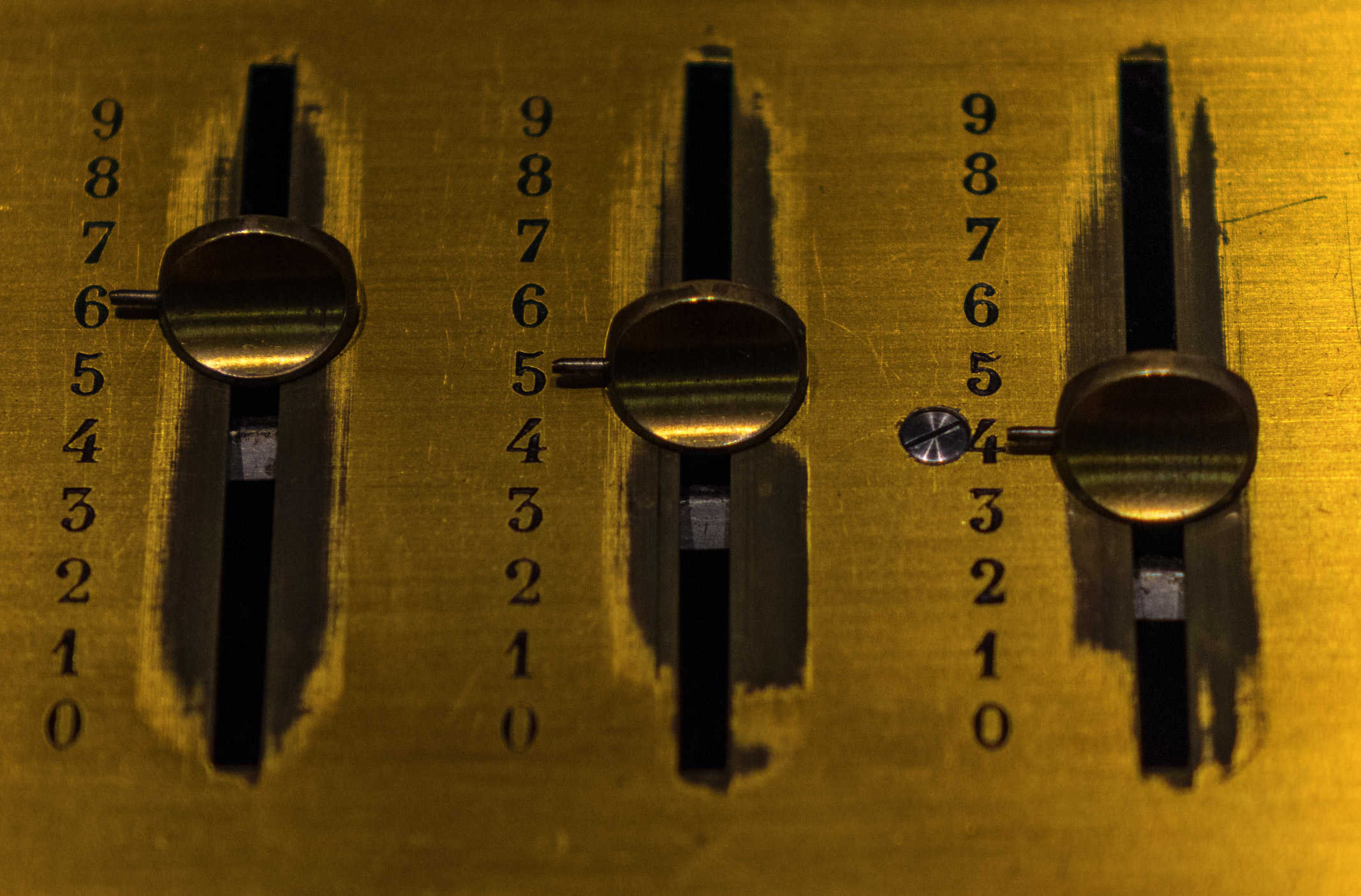

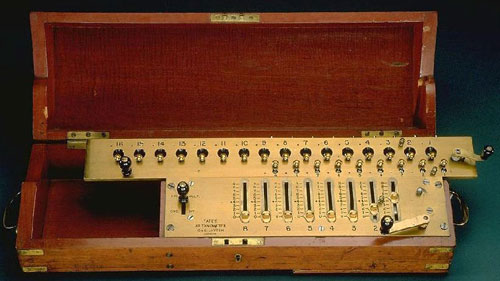

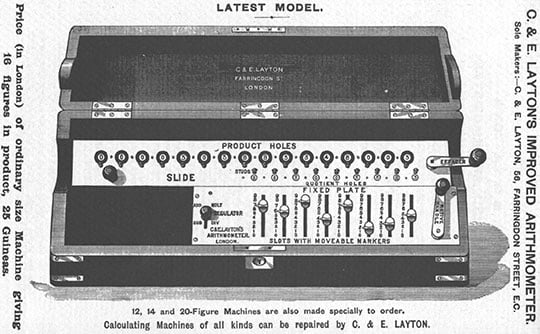

The machine was very similar to the Colmar machine, with overall dimensions of 16.5 cm x 63.5 cm x 19 cm, and was manufactured with brass and mahogany. The machine had a brass top and metal mechanism and fit into a mahogany case with a removable handle. Six or more levers were used to set digits with a stepped drum below each lever.

The plate that covered the drums and the top of the machine had slits in it to allow these and other parts to move. The edges of the slits next to the digit levers were numbered from 0 to 9 to indicate the digit entered.

An ADD MULT / SUB DIV lever was on the left of the digit levers, but the machine had no windows to show the number set up. The crank on the right side operated the machine.

Behind the levers, a carriage moved with a row of nine windows for the revolution register and a row of 12 (or more) windows for the result register. The discs in the revolution register had digits from 1 to 8 in red and from 0 to 9 in black. The discs of the result register have only the digits from 0 to 9.

Rotating the crank on the right side of the carriage zeroed these registers. Three brass decimal markers fit in holes between the levers and windows. Thumbscrews in the revolution and result registers could be used to set numbers.

Tate-Layton Machine: Historical Significance

The Tate-Layton Machine improved on the Thomas de Colmar arithmometer. It incorporated the Leibniz stepped gear principle and continued to be produced largely unchanged from 1883 to 1914.

Like previous arithmometers, the machine was popular in the insurance industry for performing complex calculations. The relatively compact size, carrying case, and handles made it portable enough to be commercially viable in the decades it was manufactured.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©iStock.com/Wlad74.