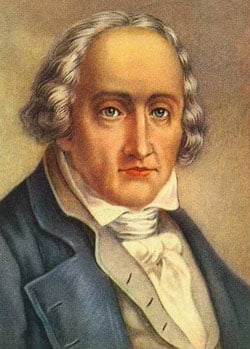

Who Was Joseph Marie Jacquard?

Joseph Marie Charles Jacquard was a French weaver who played an important role in the development of a programmable loom.

Joseph-Marie Jacquard was the inventor of the first loom to weave designs into cloth. His invention also used punch card technology, which eventually helped make computers in the mid twentieth century.

Quick Facts

- Full Name

- Joseph Marie Jacquard

- Birth

- July 7, 1752

- Death

- August 7, 1834

- Net Worth

- NA

- Awards

- Exposition des produits de l’industrie française medal

- Children

- NA

- Nationality

- French

- Place of Birth

- Lyon, France

- Fields of Expertise

- [“Computer Science”]

- Institutions

- NA

- Contributions

- Programmable Loom

Early Life

Born July 7, 1752 in the southern French city of Lyon, Jacquard worked in the silk textile industry from a young age. Similar to his parents before him, Joseph went to work at a silk mill in his hometown of Lyon when he was just three years old.

Along with many other workers during his generation, he would spend 10 hours each day working in the factory as a draw-boy. His first major task was to serve as a drawer, which he began around the time of puberty.

Sitting on a perch above the massive loom, he would spend his time before each passage of the flying shuttle to work quickly and make adjustments to warp threads of various colors in order to create the desired pattern that is ordered by the master weaver who operates the programmable loom.

The children would spend the day all over the house, setting different kinds of threads into patterns.

Despite him lacking formal education, the Industrial Revolution triggered a switch from an agricultural economy to a trade-based economy, in which few peasants supported their livelihood by farming. The textile industry thrived throughout France as factory owners responded to foreign demand for goods they could produce quickly and cheaply.

Career

Even before Jacquard entered adulthood, France found itself in perilous times, particularly for a merchant. The masses were going hungry and poor families couldn’t afford to feed their children; the number of female beggars was skyrocketing. The citizens needed change but didn’t know how this could be accomplished.

It was as early as 1775 that French Controller-General Anne-Robert Turgot supported free trade by restricting the restrictive guild system and subsidizing innovations in those industries he believed would one day make France a rival of Great Britain.

After the King of France was executed, there were more technological innovations — this trend became even more prevalent as France shifted from an absolutist monarchy to being a republic. This pattern continued following the French Revolution where Napoleon Bonaparte gained power by unleashing a new period of liberalism.

Inspired by the encouragement of the government, Jacquard sought more than his previous job as a silk mill mechanic. Considering his merchant upbringing in Lyon, he focused on innovating an alternative position to draw-boy in the industry.

In 1745, Jacques de Vaucanson developed a perforated roll of paper that controlled the weaving process. Jacquard was given one of his looms to restore and correct the unworkable design. He took on the project for several years and created an operative prototype of his programmable loom by 1790.

In 1793, as the Revolution was underway, Jacquard abandoned his project to join the Republican lower classes in attacking the French nobility.

After fighting alongside his fellow citizens in defense of the new French republic, Jacquard resumed his work in 1801. His improved draw-loom, displayed that same year at an industrial exhibition in the Louvre in Paris earned him a bronze medal.

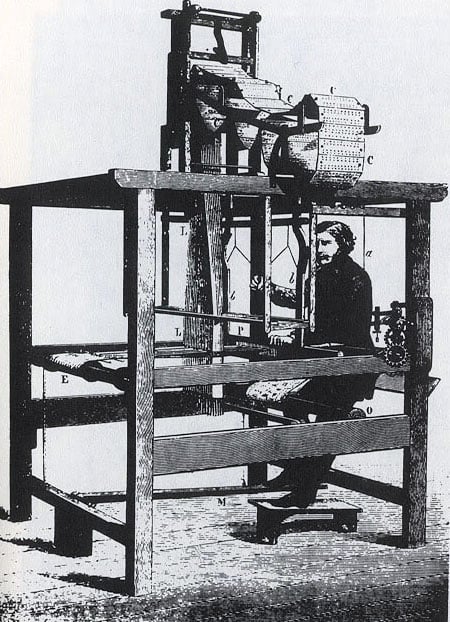

Three years later, in 1803, the inventor was again summoned to Paris. This time he had attached a large black box with movable pieces to the top of a loom. The piece allowed him to program the loom through an interchangeable door at the bottom of it that holds small paper cards connected like a belt or ribbon.

The Jacquard fabric weft technique allowed the machine to produce woven jackets and other intricately twisted silk fabrics much more quickly than by using just manual technology.

What Did Joseph Marie Jacquard Invent?

Loom

The underlying innovation in the Jacquard loom was the use of encoded punch cards to control the action of weaving, allowing any desired pattern to be reproduced automatically.

The design is encoded on a series of connected cards, with a line of holes representing one row of weave. When the cards are connected, they form a grid-like pattern.

Jacquard’s mechanism allowed each warp thread to operate independently, just like a player piano, where each note is sounded by a lever that depresses as it passes over a certain opening

In the Jacquard mechanism, a row of evenly spaced holes was punched on one side of a card. This allowed certain threads to be connected from the rod side through the card and to emerge again on other rods. The combinations matched patterns in sequence until every card had been mounted then began anew.

The Jacquard Loom is capable of weaving all fabrics with complex patterns, and that’s why they are popular for bed sheets and tablecloths. The loom can also weave a single design with various colors into the fabric.

One example of Jacquard’s work that still exists is a black-and-white portrait of himself woven using a strip from 10,000 cards. His technology would also lead to something remarkable

Jacquard’s open-hole/closed-hole system was the first use of a binary code to control automated motions that would later become known as a computer. In addition, this sequence of cards in theoretically an infinite loop is similar to the modern-day concept of “programming.”

Opposition to Innovation

When the power loom was introduced, silk weavers and others didn’t immediately embrace the technology. They saw it as a threat to their jobs and protested its use.

As of 1801, riots broke out in Lyon over changes to the traditional loom. In 1804, after Jacquard’s revised loom was introduced, and violence escalated. Attempts were made on Jacquard’s life in addition to trying to destroy any Jacquard looms that remained in use within the city of Lyon.

Though the loom’s disadvantages initially won out over its advantages, by 1800 more than 3,500 looms were in Lyon. Within a decade of this date, there were around 11,000 working looms in operation and textile mill owners had vast numbers of people on their payrolls.

France had by 1810 become a competitor in textile manufacturing with its longstanding rival, Great Britain. In 1819, Jacquard was awarded the Legion of Honor and gold medals for his role in France’s economic success. Between 1820 and 1830, the use of the Jacquard loom spread worldwide after being adopted in England.

Over 160 years after his death, the fabric manufacturing process that Joseph-Marie Jacquard once innovated is still in use around the world.

Joseph Marie Jacquard Personal Life

Born in Lyons, France in 1752, Jacquard’s parents were merchant people involved with the silk industry and he did not grow up to follow suit. Young Jacquard was apprenticed as a book binder and later as a cutler instead of joining his family’s business.

Upon the death of his parents, he inherited their home and land. He also had a small sum of money left over from them which he lost in some risky business ventures

At the time when he conceived of his automatic loom, he was participating in the revolution, and it wasn’t until 1801 that the loom was actually put into use — which is remarkable considering his lack of formal education.

Joseph Marie Jacquard Awards and Achievements

In 1804, Jacquard won a gold medal and patent for his loom invention. Local handweavers did not approve of the machine, though it threatened their livelihood. His machines were burnt in protest; he himself was attacked on more than one occasion.

Despite initial opposition, the Jacquard loom began to enjoy commercial success by 1812 and thousands were in use in France alone as education on the machine improved.

The idea of being able to store information on perforated cards strongly appealed to British scientist Charles Babbage in 1823. That year, he was given funding by the British government and started work on an analytical engine.

This steam-powered device that would be able to perform many mathematical calculations at once, printing the result. Though it was never constructed as technology of the time did not provide enough parts, Babbage’s design influenced American scientist Herman Hollerith when he built a similar machine that could compute results from the 1890 census.

This punch card machine, resembling the computers of today, was an ancestor to the modern IBM.

Joseph Marie Jacquard Books and Published Works

- Feldman, Anthony, and Peter Ford, Scientists and Inventors, Facts on File, 1986.

- Wolf, A., History of Science and Technology in the Eighteenth Century, 1939.

- Ireland, Norma Olin, Index to Scientists of the World from Ancient to Modern Times, F.W. Faxton, 1962.