Charles Stanhope

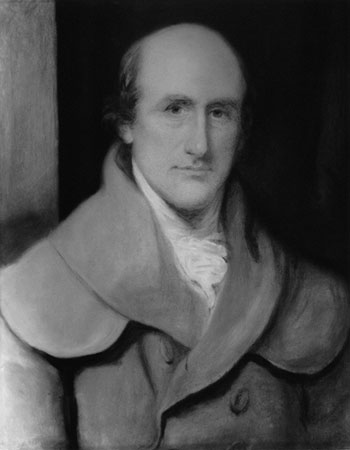

The British statesman and versatile scientist Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope and Viscount Mahon, was born in London on 3 August 1753, as the second son in the noble and rich family of Lord Philip Stanhope (1714-1786), 2nd Earl of Stanhope, a British peer, Fellow of the Royal Society and a conspicuous figure in the scientific world, and Lady Grizel Hamilton Stanhope (1719-1811). Philip Stanhope (see the lower portrait) married Grizel Hamilton, daughter of Charles Hamilton, Lord Binning, on 25 July 1745 and they had two children: Philip (1746-1763), and Charles.

Charles was sent very young (only 9 years old) to Eton College in Windsor, where his brother Philip was. Unfortunately, Philip, a very talented boy, inherited from his mother’s family the tendency to consumption, which had proved fatal to so many of the Hamiltons. He was removed to the purer air of Geneva, together with his mother, but eventually, he died in July 1763.

Charles now became Viscount Mahon, and, as the only surviving child, was more than ever the object of his parents’ solicitude. They resolved that his health should not be exposed to the English climate, or the care of his mind to the capricious attentions of the English schoolmaster. He was recalled from Eton, and the family decided to settle in Geneva.

The family continued in Switzerland for ten years, where young Charles had been educated at Leyden and Geneva under the inspection of the prominent Swiss scientist Georges-Louis Le Sage (1724-1803). He learned Greek and French and applied himself eagerly to mechanics, philosophy, and the higher branches of geometry, but not to the classics and fine arts. At seventeen, Charles won the prize offered by the Swedish Academy for the best essay on the construction of the pendulum.

At the age of 20, still in Geneva, Stanhope was already proven as a promising scientist and good athlete (he rode well, played bowls and cricket, and acquired some skill in shooting and skating). In February 1774, Stanhopes set out from Geneva, with great marks of friendship and honor shown then on leaving notre seconde patrie. They stayed several months in Paris, and in July 1774 they returned to England.

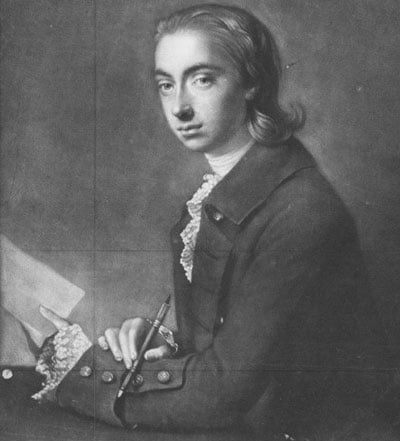

In September of the same 1774, Stanhope proposed to Lady Hester Pitt (1755-1780, see the nearby portrait), his second cousin and a sister to his friend William Pitt the Younger, the future English prime minister, and was accepted. The couple married on December 19, 1774, at St. Mary the Virgin church in Hayes. Two years later their first child — a daughter, who would become the famous British socialite, adventurer, and traveler Lady Hester Stanhope (12 March 1776 – 23 June 1839) was born. Stanhope had two other daughters from this marriage (Griselda, born 1778, and Lucy Rachel, born 1780), before the early death of Lady Hester (Pitt) Stanhope, Viscountess Mahon, in July 1780.

The death of Stanhope’s first wife was a tragedy for him, for neither his second wife nor his children inspired him with deep affection.

In January 1775, Stanhope was admitted to the Royal Society, to which he had been elected in 1773 before leaving Geneva. Stanhope’s chief interest outside politics was applied science, and he was acquainted with most of the scientific men of his day. The great drawing room at his Chevening estate was turned into a laboratory.

In 1880 Stanhope became a member of the House of Commons, upon the death of his father in 1786, when he took his place as a Peer of the realm on 7 March 1786.

Lord Stanhope was a very strange peer — a man with enormous mental energies and earnestness, who devoted a large part of his time and income not to pleasures and parties, but to experiments, science, and philosophy. According to the memories of his contemporaries, he was a tall and thin man (he was frequently compared to Don Quixote, whom he resembled not only in appearance but still more in valor and high-mindedness), who looked pale, but had a very powerful mind and voice and used to wave his arms around a lot when he was explaining things.

In 1781 Charles Stanhope married his deceased wife’s cousin — German, Louisa Grenville (1758–1829), the daughter and sole heiress of the British diplomat and politician Henry Grenville. Louisa was the mother of three surviving sons, the first of them — Philip Henry Stanhope (1781–1855) inherited not only the title Earl Stanhope but also many of the scientific tastes of his famous father. It was an unhappy marriage, and in the coming years Charles, 3rd Earl Stanhope after 1784, would fall out with all six of his children, become estranged from his second wife, and take up with a music instructor.

Lord Stanhope was most known by his contemporaries as a politician, but his reputation with posterity depended more upon his talent as a philosopher, scientist, and inventor. Politically he was revolutionary, opposed the slave trade, as well as the war against France, which earned him the nickname Citizen Stanhope, and was a supporter of education and electoral and fiscal reforms. His lean and awkward figure was extensively caricatured by his contemporaries.

Stanhope was an active member of the Royal Society. He wrote a very interesting treatise on electricity. The Lord devoted much attention to the means of preserving buildings from fire. Another object, which took a considerable share of Stanhope’s attention was the employment of steam for propulsion of vessels, for such experiments he expended very large sums. He shared his knowledge with the inventor of the first commercially successful steamboat — Robert Fulton (1765-1815).

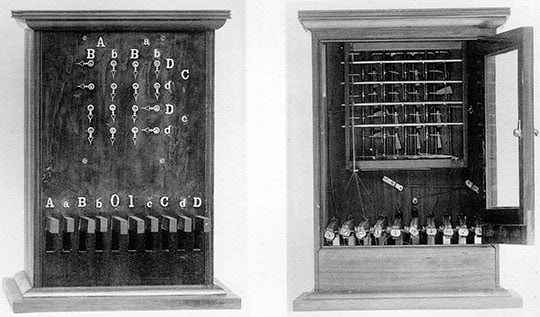

Stanhope devoted a large part of his time to calculating machines of which he invented three (see calculating machines of Stanhope). He was also a mentor and source of inspiration for the creator of the first keyboard-calculating machine in the world — James White. His Lordship also conceived the possibility of designing a reasoning machine and created two logical devices, so-called demonstrators (see the photo below), which can be used to draw the correct conclusions from logical propositions.

Stanhope is well known for suggestions for improvement in the construction of the printing press and as an early patron of the stereotype method of printing. He created a printing press with original construction (see the photo below), which will become very popular all over the world in the next century.

Stanhope invented also an optical lens, which bears his name, and a method for tuning musical instruments.

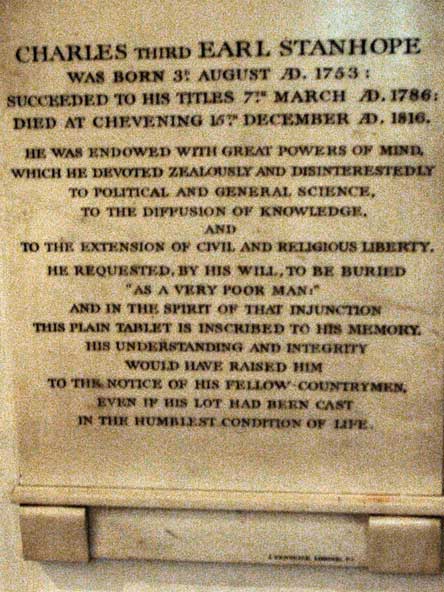

Lord Charles Stanhope died in his family seat in Chevening, Kent, on December 17, 1816, and was buried at Stanhope Chantry in St. Botolph Churchyard, Chevening. Friend and foe agreed that in the third Earl Stanhope, one of the most striking personalities of his time had passed away.

The Memorial Tablet of Charles, 3rd Earl Stanhope, and Viscount Mahon, in the Stanhope Chantry at St. Botolph Churchyard in Chevening, Kent. Charles, his wife Hester, and more of his family are buried in the underground vaults below the Chantry.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Unknown author / public domain