When we think back on military history, the focus tends to overwhelmingly skew towards things like weapons, leaders, and decisive battles. The atomic bomb, the invention of the battle tank, and the introduction of aircraft all have a tendency to dominate the conversation surrounding any sort of military innovations. That said, this isn’t the whole picture when looking at the whole of warfare, as tactics often rule the day. A technological advantage certainly is worth attaining if possible, but you also can’t discount things like enemy psychology, terrain, timing, and forcing mistakes to be made. Some tactics are so unconventional and outside the box that they seem almost like rash decisions made in the heat of the moment, but they’ve reshaped the way wars are fought.

From ancient deception to modern operational doctrines, the element of surprise can’t be ignored. It helps smaller forces to gain parity with the likes of a numerically superior foe, transformed the very nature of warfare, and has sent many military planners back to the drawing board. Weapons and technology are great, but the ability to adapt can be more valuable than pure strength. Today, we’re looking at those surprising tactics and their impact on history.

Deception

©"Trojan Horse at Troy" by ccarlstead is licensed under BY 2.0. – Original / License

The Trojan War was reputedly ended by the Greeks feigning defeat and giving a massive wooden horse as a gift. The Trojans accepted the horse, brought it into their city, and let the Greek soldiers essentially infiltrate without having to breach the walls or prolong the siege. This story doesn’t have much of a basis in reality, as ancient primary sources do little to corroborate these claims. However, one thing remains certain: deception is a powerful thing in warfare. An enemy that believes they’ve got the advantage is poised to essentially make a massive tactical error.

A more concrete example of this sort of thinking comes about during the Second World War, when information warfare was beginning to be refined. The Allies made use of falsified radio traffic, inflatable tanks, forged documents, and more to mislead the Germans before the invasion of Normandy. Operation Fortitude had German commanders fully convinced that the main invasion force would be landing far away from Normandy, which ended up delaying reinforcements.

D-Day’s success came down to many factors, but few can argue against the use of deception and the role it played in making the landings at Normandy an overall success. Sometimes, it isn’t about what territories you control, but the flow of information itself.

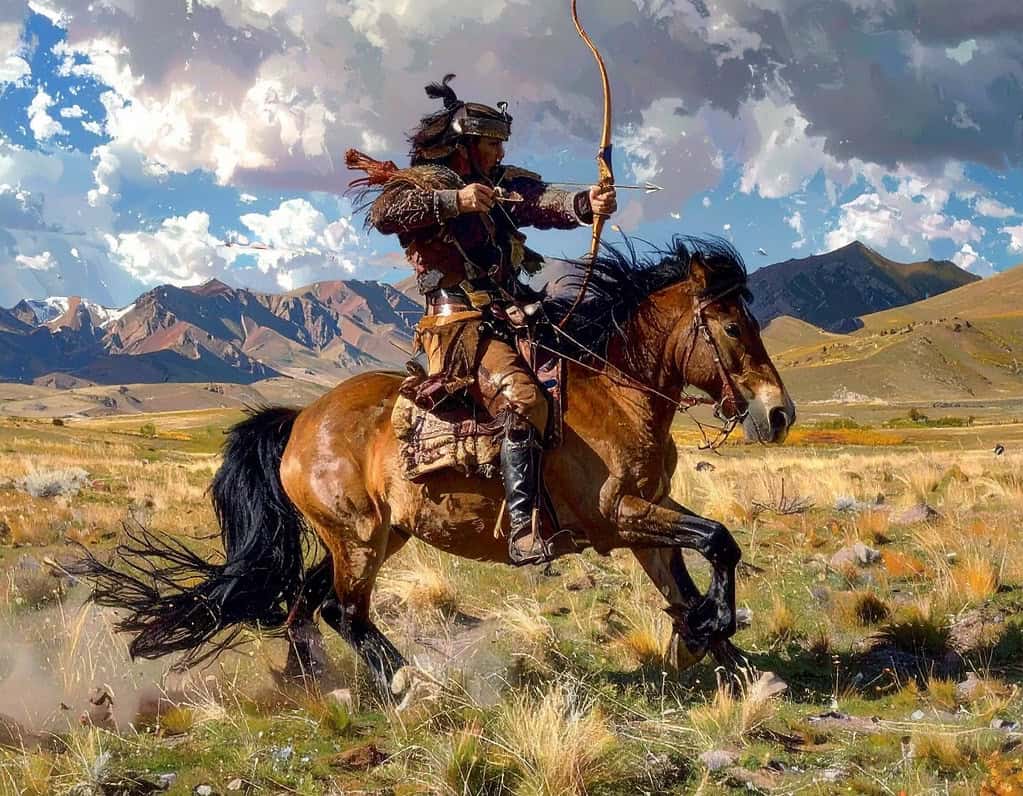

Mobility and Speed

©"A Mongol warrior aiming an arrow with a bow on his dun-colored pony with black mane" by mharrsch is licensed under BY-SA 2.0. – Original / License

Much of military history is predicated on the idea of a pitched battle. Two peer forces meet at a battlefield, assemble their formations, and conduct the battle until one side routs. With larger, piecemeal forces, like those used throughout Antiquity and the Middle Ages, this was just how wars were conducted. However, the 13th century saw the use of speed and mobility as a highly effective force. The Mongols, led by the infamous Genghis Khan, made use of mobility on an unprecedented scale for the time. Battle tactics relied on rapid movement, feigned retreats, and coordinated, multi-prong attacks.

Compared to the European and Asian armies of the time, the Mongols had a definite edge. The Mongols could easily crush rigid formations, luring their enemies into false pursuits before completely encircling them. It paid off handsomely, as well, as the Mongols were able to conquer vast amounts of Eastern Europe and Asia before their conquest was cut short. It wasn’t a campaign waged through superior numbers, but by successfully exploiting weaknesses while setting the tempo through overwhelming speed and agility.

This same sort of tactical thinking was used in 1940 during Nazi Germany’s invasion of France. Rather than settling into the old battle lines of the First World War, where attritional warfare was king, the Germans made effective use of combined arms tactics in the form of fast-moving armored formations, close air support, and supporting mechanized infantry. The goal was to breach enemy lines, disrupt command, and ultimately crush resistance before it could mount. It proved to be highly successful, as France capitulated after a month and a half or so of fighting.

Using an Enemy’s Strength as a Weapon

LAM58188 Ms 6 f.243 Battle of Agincourt, 1415, English with Flemish illuminations, from the ‘St. Alban’s Chronicle’ (vellum) by English School, (15th century); © Lambeth Palace Library, London, UK; (add.info.: great English victory over French;); PERMISSION REQUIRED FOR NON EDITORIAL USAGE; English, out of copyright PLEASE NOTE: The Bridgeman Art Library works with the owner of this image to clear permission. If you wish to reproduce this image, please inform us so we can clear permission for you.

©Unknown author / https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain – Original / License

Curiously, one of the more surprising tactics wielded on the battlefield is turning an enemy’s own strength against them. Instead of matching power against power, it relies on some clever thinking to exploit overconfidence, rigid operational doctrine, and in many cases, numerical superiority.

This sort of thinking is best exemplified at the Battle of Cannae in 216 BCE. Carthaginian forces and their commander, Hannibal Barca, faced a superior Roman army on paper. They were vastly outnumbered by what was the premier power of Ancient Europe. Rather than retreat and risk a costly, fatal pursuit, Hannibal let his center formations cede ground to the Roman legions, drawing them into a false sense of security. As the Roman forces drove further inward, they weren’t fully aware of the trap that waited for them. Hannibal’s flanks closed in, making what is still taught as a textbook double envelopment to this day, and the Romans were killed to nearly the last man by the time the dust settled.

Further ahead, we can look at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. English forces led by King Henry V were beleaguered after a long and arduous campaign. They were set to face fresh French forces, with the famed heavy cavalry proving to be a sticking point at any chance of success. English commanders made quick use of the terrain, as heavy rains had set the fields of Agincourt into a muddy mess. Defensive positions manned by England’s famous longbowmen made quick work of advancing French forces, with those same heavy cavalrymen, festooned in armor and weapons, sinking into the mud as they scrambled to close the distance.

Avoiding Battles

©"Belgium-6700 – Napoleon" by archer10 (Dennis) is licensed under BY-SA 2.0. – Original / License

Sometimes, to win the war, the best course of action is to never meet the enemy in battle. This seems a rather contradictory notion, but you have to realize that manpower and supplies are finite resources, with commanders having to spend them conservatively, lest they risk annihilation. Returning once again to the Second Punic War, Hannibal proved to be a constant thorn in the side of the Romans. Roman general Quintus Fabius Maximus came up with a rather novel strategy to wear down the Carthaginians. Rather than face them in open battle, the Romans shadowed their enemy, disrupting supply lines and forcing them to operate in hostile territory. Politically, this was a highly unpopular tactic, as the Romans prided themselves on martial strength above all else.

However, you have to remember that the previously mentioned Battle of Cannae was an unmitigated disaster for the Romans. Multiple legions met their end, with thousands dead or captured at the battle’s conclusion. The Fabian Strategy, as it would soon be known, preserved Roman strength while maximizing its advantages.

In the early 19th century, Napoleon Bonaparte and his forces were the dominant force across Europe. During the Peninsular War, the Spanish and Portuguese forces couldn’t hope to face Napoleon’s armies in battle. Instead, they made use of guerrilla warfare tactics, conducting ambushes, raids, and acts of sabotage to keep the French on their toes. Napoleon’s forces were bled dry gradually, as they stretched across the Iberian peninsula. Confronting the French in an open battle would have resulted in a crushing defeat, but the Spanish and Portuguese were able to wear them down through some rather unconventional thinking.

Technology as a Tactical Multiplier

©"A Mark I tank in action, July 1917 / Un char Mark I en marche, en juillet 1917" by BiblioArchives / LibraryArchives is licensed under BY 2.0. – Original / License

Necessity is the mother of invention, or so the saying goes. While technological advances have defined many eras of warfare, it is important to note that this isn’t the sole defining aspect of its use. Instead, where it shines is as a force multiplier. When used effectively, technology can result in dramatic shifts in tactical planning. This isn’t through the existence of these advances, but rather in their creative applications.

Take, for example, Greek fire, a Byzantine incendiary weapon used primarily for naval warfare. No nation before or since has been able to reproduce it, but it gave the Byzantine’s a tactical edge when it came to naval engagements. Smaller boats could sidle up against the massive warships of the Ottoman Empire or other foes and set them ablaze through the use of siphons. Greek fire couldn’t be extinguished, as the flame kept burning even on the surface of the water itself. Byzantium’s enemies were rarely prepared for the substance, and it helped keep the empire intact for centuries before the Siege of Constantinople.

Looking at more modern examples, we can look at the trenches of the Great War. Originally, these served as defensive structures, but they quickly proved to grind the war to a horrific stalemate. Formations couldn’t advance across open ground without being met with a blistering hail of artillery and machine gun fire. As such, it forced the military forces along the Western Front into an uneasy draw of sorts. It took some rather novel technological advances, namely the invention of the battle tank, to break the static lines of Western Europe. The horrors seen in trenches also had a profound effect on the public and military planners alike, with few wanting to repeat the same mistakes seen during the First World War.

Logistics, Logistics, Logistics

©"Marine Manning Anti-Aircraft Gun on Tulagi, Guadalcanal Campaign, circa 1942" by Archives Branch, USMC History Division is licensed under BY 2.0. – Original / License

Frederick the Great is often cited as saying, “An army marches on its stomach.” This old military axiom has existed for centuries, but the very notion has been front and center since the first major campaigns were waged. Like it or not, logistics win wars. In some cases, it isn’t a case of decisive battles, but rather the ability to keep troops supplied, aid movement, and provide the organizational infrastructure to succeed.

In Antiquity, there is no better example than the Roman Empire. They built an extensive road network, allowing troops to move with ease across vast distances, and allowing for quick responses to rebellions. Roads are somewhat boring in the grander scheme of things, at least when compared to the use of formations like the Testudo and Roman weapons. However, these standardized methods of transport allowed for quick supply. The Roman Empire also established supply depots at regular intervals, which had the benefit of letting legions resupply, rearm, and rest if necessary.

A similar strategic mindset was utilized by American forces in the Pacific Theater of World War 2. During the island-hopping campaign, the sole focus wasn’t on taking the fight to the Japanese at every occupied island, but rather on capturing logistically significant locations. They cut off supply lines while establishing their own, leaving Japanese forces isolated and effectively starved.

Conclusion

Surprising military tactics have changed the nature of warfare over centuries, reshaping the very course of history in the process. Whether it be through deception, mobility, logistics, and so forth, these strategies reveal that warfare is a contest of minds first and foremost, rather than just solely weapons.

The most successful commanders in history weren’t necessarily the strongest, but those who could roll with the punches and adapt as necessary. By studying the tactics we’ve covered today, we gain a far keener insight into how history unfolded, and why the most powerful force on the battlefield has to be creativity.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Sherbak_photo/Shutterstock.com