The Renaissance is often remembered as a period where the arts flourished, and a renewed focus on philosophy and the sciences took hold. However, that does little to address the sheer amount of military innovation that took hold during the era. Coming off the heels of the Middle Ages, and ranging from the 14th to the 17th centuries, the Renaissance was a significant time period. Most of Europe would see a shift in both social structures and the political landscape of the era. Further, the order of battle of the day was steadily changing. The aristocracy, namely the heavily armored knights, were no longer the dominant force on the battlefield. Instead, it was a period of time where firearms were starting to take hold, and the idea of a professional army was beginning to seize the minds of military planners of the era.

Gunpowder and the Shift of the Medieval Battlefield

©RHJPhtotos/Shutterstock.com

Gunpowder factors heavily into the later years of the Middle Ages, but it truly came into its own during the Renaissance. It was hard to see the efficacy of it, truth be told, at least when looking at things like early applications and firearms. Early cannons were unpredictable, often being just as dangerous to the operator as they were to the intended target. As with many ages of history, however, advances in scientific understanding and metallurgy changed the way gunpowder was approached. Stronger bronze casting techniques enabled more reliable, stronger barrels.

This was also reflected in the composition of black powder of the period, as well. It gained more overall consistency, resulting in more reliable ignition. The rise of gunpowder started to signal the shift in how warfare was fought, which is a central theme in today’s piece. This is perhaps best seen in the centerpiece of most medieval warfare, the castle. Sieges were predicated on encircling castles and hoping you could breach the walls, or starve the denizens into submission.

With more reliable gunpowder delivery systems, this wasn’t a consideration. Instead, Renaissance artillery made fortifications like castles obsolete, seemingly overnight. Thick, tall stone walls were no longer the order of the day, as a well-placed volley of cannon shots could reduce them to rubble. Instead, fortifications would evolve to make use of angled faces, absorbing cannon fire as best as they could. Overlapping fields of fire were more important for the defenders, as they could pour firepower of their own on the siegecraft.

Cannons and the Rise of the Nation-State

©"Fort Vancouver Cannon" by jim.choate59 is licensed under BY-ND 2.0. – Original / License

Artillery wasn’t just the centerpiece of the newly burgeoning modern militaries, but rather something that would soon prove to reshape the political landscape. They took up vast amounts of material, often requiring high-quality ore to be smelted. The arms industry transformed around the earliest cannons, making use of specialized labor, intricate transport networks, and requiring trained crews to operate the weapons in the first place. As you might imagine, it took a considerable amount of wealth and power to bring these cannons to the battlefield, with only the most powerful of rulers being able to make use of them.

The feudal fiefdoms of the Middle Ages were on the decline, as lesser nobles simply couldn’t afford to compete against centralized kingdoms. We wouldn’t see the murmurs of nationalism for centuries to come, as the 19th century would provide the great leap toward unification and a shared national interest among the population. However, we can see the first murmurs of change as centralized states and arsenals begin springing up in the Renaissance to support these weapons.

Firearms and the Decline of Knights

©"Armour and arquebus" by quinet is licensed under BY 2.0. – Original / License

If the cannon transformed sieges, the arquebus changed the nature of combat itself. Early muskets, like the previously mentioned arquebuses, became commonplace on European battlefields starting in the 15th century or so. It was slow to reload, unreliable in wet weather, and inaccurate, but that didn’t matter. When massed together in formation, dozens or hundreds of these muskets could tear through ranks of costly, heavy cavalry like knights.

This was a notable change from the past few centuries, where knights and the aristocracy dominated the battlefield. There were few means of opposing the noble houses, as knights could raise their own weapons and armies. Further, they had the training necessary to make warfare a reality, something that a peasant tending a subsistence farm couldn’t measure up to even in the best of conditions.

With the introduction of personal firearms, those advantages evaporated. You could train a cadre of men in weeks, rather than over whole lifetimes. Ranks of knights were just as susceptible as pike and shot as any peasant levies raised across fiefdoms. The age of the warrior class was drawing to an end, at least in its most literal sense.

Traditional Arms in a Changing World

©"Pike with motto" by quinet is licensed under BY 2.0. – Original / License

Things like bladed weapons didn’t simply disappear thanks to the advent of portable firearms. This was the era of pike and shot, as I stated previously. The pike became vital to infantry, allowing foot soldiers to contest ground against cavalry. Much like the musket, its efficacy didn’t lie in individual prowess, but rather in ranked discipline. This was a prevailing notion throughout the Renaissance, as professional armies began to take hold.

Swords were still ever-present on the battlefield as well, but they were changing from something intended to take on armored opponents into something lighter and more intended for personal combat. The longsword would give way to personal weapons like the rapier, alongside the saber. These sorts of blades weren’t intended for fighting against armored opponents, but rather for different use cases.

The rapier, in particular, marks a notable shift in how violence was perceived. It might not have served as a weapon of war in the strictest sense, but it showed a ritualization of violence. The chivalric standards of the Middle Ages were being set aside in favor of notions like honor and reputation, as saving face became more important.

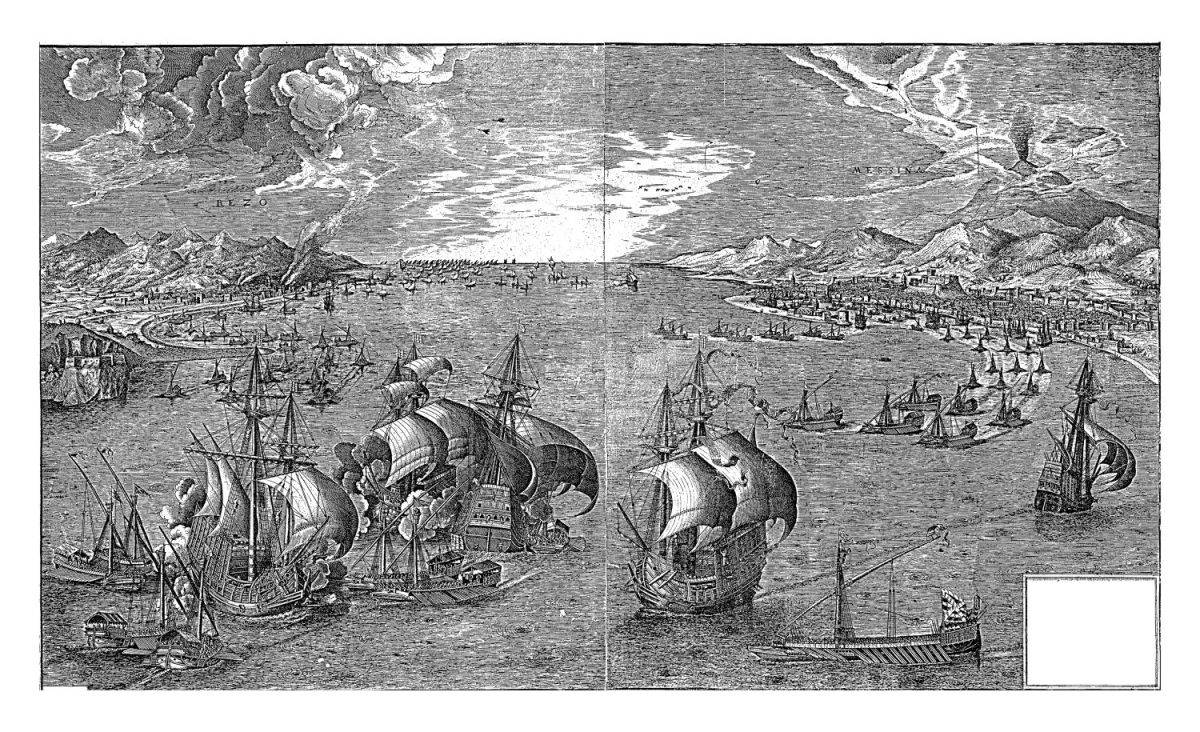

Shifts in Naval Warfare

©Morphart Creation/Shutterstock.com

The shift toward gunpowder wasn’t something that was intended solely for the infantry. Naval warfare changed in some big ways during the Renaissance. The introduction of cannons as standard armaments meant that naval fleets weren’t intended solely as boarding platforms, but could become mobile artillery. This played a massive role in European colonialism and expansionism, as smaller fleets could release devastating amounts of firepower wherever they went.

Small forces could dominate coastal trade routes, something that would heavily influence the influx of new resources obtained from the Americas. While naval technology only played a small part in this, there is no denying the shift in naval doctrine for the era. For centuries, naval vessels served to wage war through ramming actions, boarding, and other raiding tactics. The introduction of the cannon meant that crews could forestall engaging in fierce hand-to-hand combat, often sinking other vessels before considering closing distance for boarding.

The nature of warfare at sea and on land had changed, and the innovations of naval warfare during the Renaissance would set the stage for future naval tactics seen during the Age of Enlightenment and Industrial Age.

Conclusion

By the end of the Renaissance, warfare had fundamentally changed. The time period started off not being too dissimilar to the late Middle Ages, with armored knights and crude firearms alongside the likes of crossbows and longbows. By the dawn of the Age of Enlightenment, the warrior classes were all but gone, with professional armies taking hold. Politics had changed right alongside the battlefield, as logistics and technology began to be the trump card of nations, rather than raw martial prowess. If anything, the Renaissance isn’t solely a period of artistic innovation and a renewed appreciation of the sciences, but rather the dawn of the modern age when it comes to military planning.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Pegasene/Shutterstock.com