As the Second World War drew to a close, the Cold War started as the Soviet Union and the United States began consolidating their spheres of influence and drawing lines in the sand. While the United States was primarily an industrial hub, the Cold War saw a notable shift in how research and development for the military were conducted. In some cases, entire towns were built, hidden away from public maps to help support and shield these projects for decades. Sometimes, these hidden cities served a key role in nuclear deterrence, at least before the advent of mutually assured destruction. Today, we’re looking at some key American towns and their role in the Cold War, along with the overall function they served.

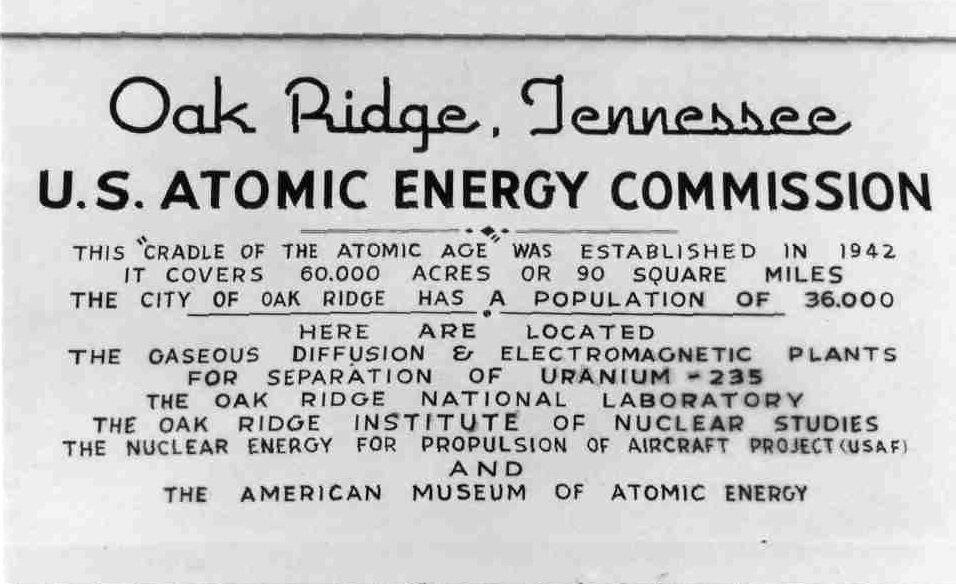

Oak Ridge, Tennessee

©"Oak Ridge Tennessee Pics0003" by bsabarnowl is licensed under BY 2.0. – Original / License

Although the foundations for this town were set in the Second World War, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, would go on to be one of the most vital sites for dedicated nuclear production. Originally, it was planned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, meaning this wasn’t a repurposed town, but rather one built for the express reason of clandestine nuclear research and enrichment. At its peak, the population of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, reached around 75,000. If you were to go look at any maps or atlases, you wouldn’t have seen it. Any residents of the town were strictly forbidden from discussing their work.

Enrichment was the primary force driving any investment and development in Oak Ridge, with Y-12, K-25, and X-10 being among them. The bigger picture was lost in the shuffle of enrichment, with workers not knowing what their individual tasks factored into. After the war’s end, Oak Ridge could’ve been shuttered, but it continued on with enrichment and development for nuclear arms during the Cold War.

Despite the Cold War ending in the 1990s, Oak Ridge continues to develop its nuclear industry. There have been challenges, as the town’s lock-and-key nature is very much at odds with integrating into the wider Knoxville metro area. That said, it still remains a site for federal work, albeit at a far smaller scale than its heights during the 1940s and 1950s.

Los Alamos, New Mexico

©United States Department of Energy / https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain – Original / License

Of the many towns and cities that played a role during the Cold War, few carry the same sort of fame and mystique as Los Alamos, New Mexico. The Manhattan Project famously progressed here, with scientists like J. Robert Oppenheimer at the helm. Los Alamos would be where the United States harnessed the power of the atom, developing Fat Man and Little Boy. After the Second World War, Los Alamos remained a central site for the development of nuclear weapons, with the test of Ivy Mike taking place in 1952.

It remained a classified location, accessible only by a pair of gates. Its population was largely comprised of physicists, engineers, and military administrators. It opened to the public in 1957, doing away with much of the secrecy surrounding it. The potential for a nuclear war permeated throughout Los Alamos’ history, with Girl Scout troops camping out in a fallout shelter and the threat of unexploded ordnance showing along the hiking trails surrounding the town.

Interestingly, Los Alamos is one of the wealthiest locations in the United States, having one of the highest concentrations of millionaires in the general population. The thought of nuclear war might be out of the minds of the American public, but there is something to be said for just how important Los Alamos was for the Second World War and the Cold War.

Richland, Washington

©"Timmerman Ferry site in Richland, Washington 5" by Allen4names is licensed under BY-SA 3.0. – Original / License

Richland, Washington, was another town established specifically to support the Manhattan Project. The town was established in 1943 and became home to the Hanford Engineer Works and B Reactor, the first full-scale plutonium reactor ever built. Plutonium from Richland would go on to be used at Trinity, the first nuclear test, along with being used in the Fat Man bomb deployed at Nagasaki in 1945. The Cold War saw Richland’s reactors expanded, with 9 nuclear reactors and 5 large plutonium processing complexes. More than 60,000 weapons built for the United States’ nuclear arsenal made use of the material developed here.

By 1958, it became self-governing, no longer under the direct control of the federal government. Residents were allowed to purchase their properties. Production reactors were shut down between 1964 and 1971, after a suitable amount of plutonium had been produced. Richland’s environmental legacy is a bit mired in inadequate processes and dangerous waste disposal methods. A significant amount of radioactive material was released into the air and along the Columbia River, driving up cancer rates in the surrounding areas.

The Hanford Site would become the focus of one of the largest environmental cleanup efforts in United States history. Cleanup activity is still ongoing, with over 10,000 workers pushing towards a cleaner environment. The Cold War’s legacy remains in Richland, and will for the foreseeable future. It remains a curiosity for Cold War history buffs.

Mercury, Nevada

©"You Are Now Entering the Nevada National Security Site (No Trespassing), Near Mercury, Nevada" by Ken Lund is licensed under BY-SA 2.0. – Original / License

5 miles north of U.S. Route 95 and 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas lies Mercury, Nevada, home to an astonishing 928 nuclear tests between 1951 and 1992. The village itself was started in 1950, with support staff, scientists, and military personnel being the primary residents. Nuclear detonations were rather frequent, with atmospheric detonations even factoring into the Las Vegas nightlife.

Unlike some of the other support towns and villages established for the Cold War, Mercury’s population never saw a major boom. At its height, the village never exceeded 10,000. After 1992, the village was essentially put on life support following the United States’s being one of the signatories to the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. A skeleton crew of military personnel and scientists remains in Mercury to this day, conducting limited testing and research. Many of the amenities established to entertain the village’s residents have closed.

The population has shrunk substantially, with the last U.S. census only accounting for around 500 people in total. If anything, Mercury remains a curiosity and relic of the Cold War.

Miamisburg, Ohio

©"Market Square (Miamisburg, Ohio) Main St 1" by Pjsham is licensed under BY-SA 3.0. – Original / License

Miamisburg, Ohio, was founded well before the Cold War, being founded in 1797 and being later incorporated in 1832. After the Second World War, work began on establishing a more permanent location for the Dayton Engineer Works, which would later end up as Mound Laboratories. Mound would go on to produce detonators, cable assemblies, firing sets, and other equipment needed for the development of nuclear weapons.

By 1954, Mound would start developing tritium, mainly through the disassembly of bomb components and repurifying it. Non-radioactive isotopes were also produced at Miamisburg, producing a variety of materials for the nuclear arsenal. Despite being a normal civilian town, few in Miamisburg knew about what was happening in their backyard.

The site itself remained active until 2006, with the cleanup of the site beginning in 1995. Tritium repurification ended in 1997, with the site’s cleanup finally coming to an end in 1997.

Boca Raton Army Air Field, Florida

©"Mid-Century Brutalist IBM Building Boca Raton 1970 Marcel Breuer" by Phillip Pessar is licensed under BY 2.0. – Original / License

In the 1940s, Boca Raton, Florida, was a backwater, with only a population of 723. The United States government was able to purchase thousands of acres without the fear of the relocation of thousands of civilians. During World War 2, the Air Field was primarily used for classified weapons research, namely in sabotaging agricultural efforts in Japan. By 1944, it was being used as a training facility for B-17 and B-29 to learn radar bombing.

After the war, as the Cold War began in earnest, the Boca Raton Army Air Field would become a vital testing facility for experimental jet craft. However, the more alarming testing began thanks to the U.S. Army Chemical Corps, with the pursuit of biological weapons taking place in the eventuality of a potential escalated war with the Soviet Union. Tests were undertaken to find a potent fungus to wipe out wheat crops in the Soviet Union, starving millions in the event of an all-out war.

By 1957, the project had come to a close, with 1969 seeing all chemical projects destroyed and related materials destroyed under the order of then-President Richard Nixon. Unlike some of the other sites mentioned, the chemical work done at Boca Raton Army Air Field hasn’t left a massive cleanup effort. A 1994 survey of the location found no lasting damage or contaminants.

Conclusion

The secrecy surrounding the American efforts in the Cold War wasn’t solely confined to clandestine testing sites and underground bunkers. To gain an edge over the Soviets, the United States made this sort of work embedded in the very fabric of towns and villages. For many in these places, life went on as usual, with families raised despite the classified nature of the work being conducted. It has taken decades for the truth of the work done at these facilities to be known, and it gives a glimpse of what life was like at the height of the Cold War, at the epicenter of cutting-edge research and development. Thankfully, we don’t have to contend with national security shaping and molding entire populations due to the threat of an impending nuclear war.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©U.S. Department of Energy / https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain – License / Original