Key Points:

- Count Niccola Guinigi-Magrini was an inventor from Lucca, Italy who designed and produced a dial adder called the Manipolatore Aritmetico—Arithmetical Manipulator.

- Guinigi was a member of the Organizing Committee of the Fifth Meeting of Italian Scientists in 1843, and a representative to the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1855 and the Dublin International Exhibition of 1865.

- In December 1858, Guinigi submitted the finished calculator to the Accademia Toscana for review, who gave it a generally good review, but recommended it be improved upon.

Manipolatore Aritmetico of Niccola Guinigi

(Created with the expert advice of Mr. Silvio Hénin, Milan, Italy)

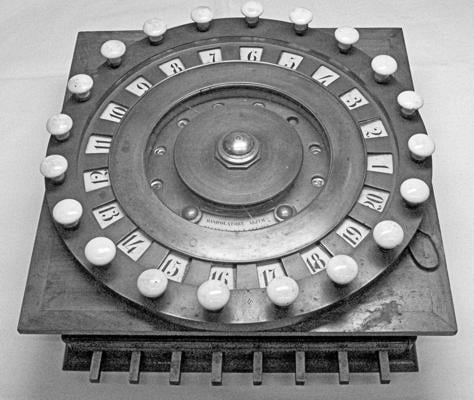

In the 1850s (or even earlier) Count Niccola Guinigi-Magrini, a nobleman from Lucca, Italy, designed and produced a simple dial adder (which he called Manipolatore Aritmetico—Arithmetical Manipulator) with a unique design that summed eight-digit figures up to 99,999,999. Now the only surviving device is exposed in the Arithmeum Museum, Bonn, Germany (see the lower image).

On the lid of the device is attached an engraved brass plate with the inscription N. GUINIGI Invento ed Eseguı 1858 (N. Guinigi Invented and Built in 1858). Guinigi even asserted that he had used his Manipolatore for 19 years while performing the duty of some administration task in the town council of Capannori, near Lucca. So probably his device had been designed much earlier than 1858.

Together with the machine was preserved a seven-page manuscript, handwritten by the inventor himself, entitled Manipolatore Aritmetico, which describes the calculator in detail and explains how to use it, with practical examples. The manuscript states: Purpose of this small machine is to perform additions, driving them to an easy game for everybody, doing away with computing and carrying, always to a correct outcome. The user does not need more knowledge than just [reading] numbers. A quarter of an hour suffices to master the machine operation.

In December 1858, Guinigi submitted the finished calculator to the Accademia Toscana. The device was examined by a commission of two mathematicians, Giovanni Novi and Antonio Ferrucci, who wrote a report, which concludes: this [machine] is particularly worth mentioning for its simplicity and the solidity of its organs… with no essential fault… [but] presents some flaws in its construction…. The report recommended the inventor introduce some improvements in the construction.

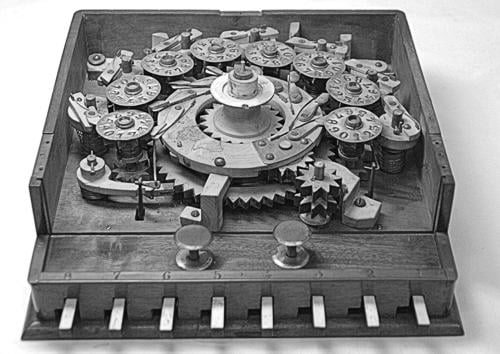

Guinigi’s adder is a wooden box (dimensions: 37 x 38 x 18 cm, weight: 9 kg) with a large circular dial on the top. Inside the large dial is a glass plate covering eight small, round windows showing eight digital wheels. The gears, levers, axles, and cams were made mostly of boxwood, but an internal brass slab that holds the accumulator and carries axles and other small elements (screws, pins, and springs) is made of brass or steel.

The large dial has 20 knobs on its circumference, featuring the numbers 1 to 20 inscribed on an internal circle. The dial can be rotated clockwise by the knobs until a stop is reached (just like a rotary telephone dial). On the front side, eight levers (numbered 1 to 8) stick out; each one can be pressed down, but an internal device prevents pressing more than one at a time.

The mode of operation of the machine described by Guinigi in his manuscript seems really easy: having a vertical list of numbers to sum, the addition is made by columns, starting on the right, as accountants do with pen and paper. The rightmost front lever is pressed and each digit of the units column is entered in succession by pressing the respective knob on the dial wheel and turning it clockwise until the stop is reached (zeros are ignored).

Tens carries are automatically added to the next decimal order. Then the rightmost lever is raised and the one to its left pressed; the tens column digits are entered as before. The procedure is then repeated for all the columns and the result can be read in the small windows under the glass cover.

Guinigi obviously realized that his machine is subject to jamming when a ripple carry occurs (as was the case with most previous and coeval calculators) for example when adding 1 to 99999. The two brass buttons on the front side are designated as antijamming devices. The machine also lacks (again as most calculators of the time), a device of critical importance—for zeroing. To reset the counter wheels, the operator must add the complement to 10 to each accumulator, starting with the rightmost one.

Guinigi wrote in his manuscript, that intended to make [the machine] again, in metal and more precise, but both for lack of will and for shortage of time… making it in metal with a new design remained, and I think will remain forever, just a wish. So obviously the above-mentioned device remained only as a prototype and was not developed further and popularized.

So, who was the inventor Niccola Guinigi? Strangely, the information for him is very scant.

Count Niccola Guinigi-Magrini was born in 1818 in Lucca, a Bourbon-Parma duchy in Tuscany, Central Italy. He was one of the last descendants of a famous Lucchese family of wealthy and powerful merchants. Guinigi’s most renowned ancestor was Paolo Guinigi (1372-1432), who ruled Lucca from 1400 until 1430.

Niccola Guinigi was part of the local aristocracy, a man of liberal mind and progressive ideas, and an active partaker in the public life of Lucca. He was a member of the Organizing Committee of the Fifth Meeting of Italian Scientists in 1843 and also a representative to the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1855 and the Dublin International Exhibition of 1865.

In May 1848, Guinigi fought in the battle of Curtatone against the Austrian imperial forces. In 1849, while serving in the Lucca’s Civil Guard (he was an officer and a head of the Civil Guard), was taken prisoner by rioters and sentenced to death, but eventually escaped the execution. Later on, Guinigi held public positions in Lucca, as chairman of the Royal Commission for the Conservation of Fine Arts and Encouragement of Arts and Manufactures and president of the Departmental Council.

Count Niccola Guinigi died on 25 January 1900, leaving no issue.

Literature: Silvio Hénin, Massimo Temporelli, “An Original Italian Dial Adder Rediscovered”, IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 2012, vol. 34, n. 2

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Unknown author / public domain