Karel Capek

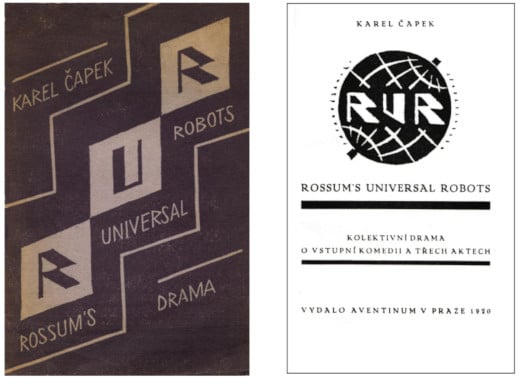

The robot word was conceived at the beginning of 1920 by the Czech writer and playwright Karel Čapek (see biography of Karel Čapek) (with the help of his brother Josef, an acclaimed painter, graphic artist, writer, and poet), and was introduced in his drama R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), published in November, 1920 (see the lower image).

Since then, and almost immediately, the robot word has become a universal expression in most languages for artificial intelligence machines, invented by humans.

How was the word robot invented, and what it means?

The cover of the first edition of R.U.R., November 1920 (left); the title page of the first edition (right)

Karel Čapek described the occasion some 13 years later in the newspaper Lidové noviny of 24 December 1933 (in Kulturní kronika column, on page 12, see the text in English and the original report below):

“The note of prof. Chudoba about mentioning of the Robot word in Oxford dictionary and its derivation in English, reminds me that I have an old duty. The author of the play RUR did not, in fact, invent that word, he merely ushered it into existence. It was like this: the idea for the play came to said author in a single, unexpected moment. And while it was still fresh he rushed immediately to his brother Josef, a painter, who was just standing by the easel, vigorously painting at a canvas.”

“Listen, Josef,” the author began, “I think I have an idea for a play.”

“What kind of?” the painter mumbled (he really did mumble, because at the moment he was holding a brush in his mouth). The author told him as concisely as he could.

“Then write it,” the painter said, without taking the brush from his mouth or stopping to work on the canvas. His indifference was quite insulting.

“But,” the author said, “I don’t know what to call those artificial workers. I could call them Laboři, but that strikes me as a bit literal.”

“Then call them Roboti,” the painter muttered, brush in mouth, and carried on painting. So it happened…How was the drama R.U.R. inspired?

Although in the second half of his life, Karel Čapek became a keen anti-fascist and anti-communist, as a young he was preoccupied with the difficult conditions of the factory workers and the brutal attitude of their managers ever since writing the story Systém (Krakonošova zahrada ) together with his brother Josef, published in 1918.

The memory of the Úpice (the hometown of Karel) textile workers on strike whom he had witnessed, seeing their march through the town, and the knowledge of newly introduced mass production and scientific management methods of manufacturing became his inspiration.

In Systém Čapek brothers described the action of a greedy factory owner who tried to employ workers devoid of human needs, ideas, and emotions, purely to be used as automata and working machines to achieve the most efficient manufacturing means.

Josef Čapek (left) and Karel Čapek (right) in the middle 1930s. The brothers were quite different: Josef was an introvert, while Karel was more open and had a lot of friends.

Further inspiration came at the beginning of 1920 when Karel took a tram from Prague’s suburbs to the city center. The tram was so uncomfortably overcrowded, that people were pressed together inside, even spilling outside onto the tram steps, appearing not like herded sheep, but like machines.

Thus Karel imagined people not as individuals but as machines and during the journey thought about an expression that would describe a human being only able to work but not able to reason.

With that in mind, in the spring of 1920, Karel began to write a drama about the manufacture of artificial people from synthetic organic material who would free humans of work and drudgery, but finally due to overproduction those roboti would lead humankind to destruction and annihilation.

The play describes the activities of Rossum’s Universal Robots (R.U.R.) company that makes artificial people from man-made synthetic, organic matter. These beings are not mechanical creatures, as they may be mistaken for humans and can think for themselves.

Initially, they seem happy to work for humans, but that changes with time, and at the end a hostile robot revolt points to the extinction of the human race, perhaps to be saved by a male robot and a female robot acting as Adam and Eve.

R.U.R. premiered in January 1921 and quickly became famous and influential in both Europe and North America. By 1923, it had been translated into thirty languages. The play was described as “thought-provoking”, “a highly original thriller”, “a play of exorbitant wit and almost demonic energy” and was considered one of the “classic titles” of inter-war science fiction.