Judah Levin’s Adding Machine History

Yehuda Leib Levin was born on March 26, 1863. He was the son of Nachum Pinchas and was born in Traby, Vilna Province, Russian Empire (now a small town in Lithuania). Levin’s father died when he was eight years old and his uncle, rabbi Abraham Abramowitz, was an esteemed Talmud scholar who assumed the responsibility of raising him.

When Levin was 19, he went to study Talmud in Volozhin and Kovno and received rabbinical ordination. Shortly after his marriage to the daughter of a rabbi — Esther Rhoda Trauber-Levin (1863-1933) — Judah Levin, at age 24, became rabbi at Liškiava, Suwalki Province, now a village in Lithuania. The family had four sons: Nathan, Samuel (1888-1975), Isadore, and Abraham.

Quick Facts

- Created

- 1902

- Creator (person)

- Judah Levin

- Original Use

- Addition and subtraction

- Cost

- N/A

In 1892 Levin immigrated to America where he accepted a rabbinical position in Rochester, New York. Two years later, he returned to Russia to become a rabbi in Kreva (now Belarus). Within a year, Levin returned back to the United States to serve as rabbi in New Haven, Connecticut. In 1897 he was invited by three Orthodox synagogues of Detroit to serve as their rabbi and he remained there for the rest of his life. He also helped support the needs of the Jewish community during a period when it was experiencing tremendous growth.

Levin was an inventor by avocation and he secured three patents for the invention of his calculating machines (US706000 from 1902, US727392 from 1903, and US815542 from 1906). Levin was an ardent supporter of religious Zionism.

Though not a prolific writer, he published two volumes of sermons and commentary. Judah Levin died in Detroit on March 27, 1926, at the age of 63, leaving many unpublished manuscripts.

Judah Levin’s Adding Machine: How It Worked

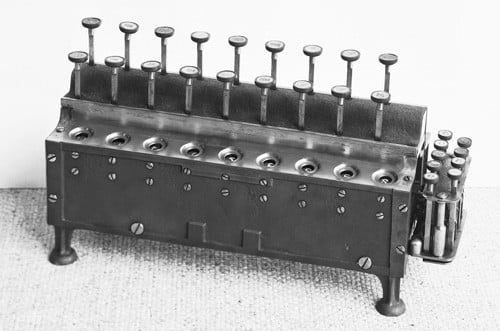

Judah Levin’s adding machine had a steel frame, plastic and paper keys, and a leather and velvet suitcase. Its overall measurements were 25 cm x 39.5 cm x 15.4 cm.

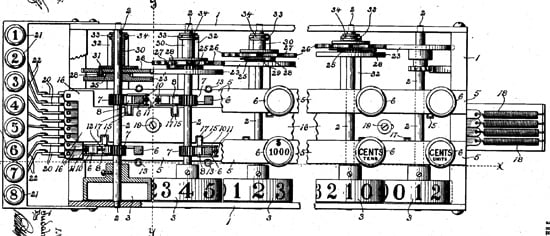

The ten-key arrangement was in one column on the patent drawing but was soon arranged into two columns on the left side of the device. Two rows of nine operating keys across the top indicated the place number of the digit entered. The front row was for addition and the other was for subtraction operations. To enter a number, both the digit key and the place key were depressed.

By providing two sets of keys, one for determining the digits and the other for determining the value of each digit or its place in the number and also to operate the mechanism, the speed of operation was greatly increased and the liability of mistakes was lessened since the keys were operated in the same order in which the person would call or write the number. Writing or speaking “4000,” for example, required the digit “4” to be expressed first and then its value or place in the number.

Numbers through 9,999,999 could be entered. The metal ten-key design had plastic and paper keytops. The space under the keyboard was covered with green velvet. The result was indicated on a row of red number wheels below these two rows of keys. The machine was stored in a small black suitcase covered with leather, lined with cloth, and provided with a metal handle on top.

Judah Levin’s Adding Machine: Historical Significance

Judah Levin built upon the work and inspired the work of a significant historic group of inventors who were Jewish. This historic group included Abraham Jakub Stern, Chaim Zelig Slonimski, David Roth, Izrael Abraham Staffel, and Jewna Jakobson. A model of the third Judah Levin adding machine invention from 1906 was placed on a permanent exhibit at the Smithsonian Institute in 1938.

The Papers of Rabbi Judah Levin

Rabbi Levin penned two books in three volumes titled Sefer Ha-Aderet Veha-Emunah. He shared his ideas on biblical matters and various Talmudic tractates. He also included notebooks, family biographical information, details on his patent, and more.

There are 22 notebooks in total in the collection, and he wrote them in Yiddish, Hebrew, and English. Most of the notes are drafts of sermons and lectures he gave in varied synagogues, but he also left notes and ideas that were undeveloped to completion. Sermons and lectures were arranged under the titles: Ceremonies, Biblical Sermons, Holidays and Festivals, Additional Talmudic Sermons, and General.

Rabbi Judah Levin: Jewish Community Activism

By the turn of the century, Rabbi Levin had accepted an appointment as the Chief Rabbi of the United (Orthodox) Jewish Congregations of Detroit. At that time, Eastern European Jews were immigrating to Detroit. Rabbi Levin was responsible for facilitating the creation of a myriad of organizations and institutions that served Detroit’s rapidly growing Orthodox Jewish community, including a Hebrew education system and a school. He also helped feed the poor and established Jewish cemeteries.

With such a busy schedule, it’s hard to imagine when he found time to focus on his inventions, but he made a tremendous impact on the work of other Jewish inventors as well.