Four Facts About Comptometer

- The Comptometer is known to be the first key-driven adding and calculating machine.

- Comptometers were in use until the 1990s when developments in computer technology rendered them obsolete.

- In 1889, the Comptometer’s inventor added a printing mechanism and received a patent for the Comptograph, a prototype for modern-day adding machines.

- Margarete (Marg) and Lawrence Speer of Maple Ridge were the original owners of the Model J comptometer, which is now on display at the Maple Ridge Museum.

Comptometer: History

In 1884, a young machinist named Dorr Eugene Felt at Ostrander and Huke machine workshop in Chicago observed how a planing machine controlled varying depths of cut and speculated an idea from watching its ratchet feed motion was indirectly responsible for the final solution of the multiple-order key-driven calculating device. His mind wandered to the possibility of using a similar strategy for creating a whole new kind of calculator, one that would be revolutionary in its time.

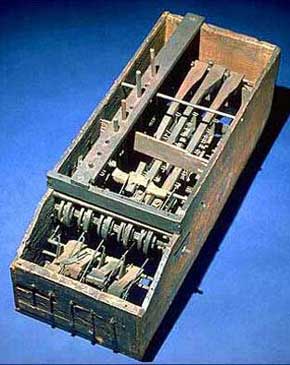

Dorr Felt created a wooden model out of rubber bands, meat skewers, twine, staples, and a macaroni box, which he completed in early 1885. This variant was eventually labeled the “macaroni box” model. The main benefits of this new calculating machine were its speed, adaptability, and simplicity of use. Model J was introduced in 1926 and was in production until 1939. This “shoebox design” had a metal enclosure, which was used on comptometers until 1942. Because of its robust construction, the machine was more dependable because it needed fewer repairs. It also included green keys instead of the standard black keys for a fresh design.

Quick Facts

- Created

- 1885

- Creator (person)

- Dorr Eugene Felt (American inventor and industrialist)

- Original Use

- The comptometer was designed to do addition and subtraction, it was also capable of performing other operations, including multiplication and division.

- Cost

- NA

Let’s quote Felt himself: Watching the planer-feed set me to scheming on ideas for a machine to simplify the invention hard grind of the bookkeeper in his day’s calculation of accounts.

I realized that for a machine to hold any value to an accountant, it must have greater capacity than the average expert accountant. Now I knew that many accountants could mentally add four columns of figures at a time, so I decided that I must beat that in designing my machine. Therefore, I worked on the principle of duplicate denominational orders that could be stretched to any capacity within reason. The plan I finally settled on is displayed in what is generally known as the “Macaroni Box” model. This crude model was made under rather adverse circumstances.

The construction of such a complicated machine from metal, as I had schemed up, was not within my reach from a monetary standpoint, so I decided to put my ideas into wood.

It was near Thanksgiving Day of 1884, and I decided to use the holiday in the construction of the wooden model. I went to the grocer’s and selected a box that seemed to me to be about the right size for the casing. It was a macaroni box, so I have always called it the macaroni box model. For keys, I procured some meat skewers from the butcher around the corner, some staples from a hardware store for the key guides, and an assortment of elastic bands to be used for springs. When Thanksgiving day came I got up early and went to work with a few tools, principally a jackknife.

I soon discovered that there were some parts which would require better tools than I had at hand for the purpose, and when night came I found that the model I had expected to construct in a day was a long way from being complete or in working order. I finally had some of the parts made out of metal, and finished the model soon after New Year’s day, 1885

When work slowed at the O&H workshop, Felt connected with A. B. Lawther who, impressed with an elevator invention Felt had devised, gave him a place to work in return for an interest in any resulting invention. At some point, his old employer, Ostrander, suggested that Felt buy out Lawther’s interest and he did so by borrowing $800 from a cousin, Chauncy W. Foster. Apparently this early “venture capital” was sufficient to finance the materials to build his first machines as well. Over the next two years, the design was refined into a metal mechanism while retaining its wooden case. Interestingly, Felt’s first patent in 1885 (USA #366945) would assign the invention to Foster and himself. The first practical model was ready in the fall of 1886 (see the nearby image).

In 1886 Charles Joseph DeBerard, an accountant and Vice President of Tarrant Foundry in Chicago introduced the young Dorr Felt to Robert Tarrant, owner of machine shop and foundry. In 1887, Robert Tarrant, intrigued with Felt’s ideas, signed him on as a helper at $6 a week and gave him a bench in the rear of the shop where Felt could work on his invention. Over a period of time, Tarrant advanced Felt about $5000 for materials and parts and other expenses involved in the development of the calculating machine. Since Foster was anxious to get his investment back, this too was covered by Tarrant money. On November 28, 1887, a partnership was formed and 14 months later, incorporated as the Felt & Tarrant Mfg. Company (400 shares of stock, Felt getting 225, Tarrant 150 shares, and DeBerard the remaining 25 shares.

By the end of 1887 four of the eight machines that the company had built that year were installed in the U.S. Treasury offices. The remaining four machines were then bought by Chicago businesses. These businesses soon found they needed skilled operators to get the maximum benefit from their $400 purchases. This was one of the first times businesses needed skilled operators in such a capacity and training was given as necessary by the Felt and Tarrant Manufacturing Company (see the nearby drawing).

Comptometer: How It Worked

Comptometers were mostly used for addition, although they could also be used for subtraction, multiplication, and division. In addition, special models were sometimes constructed to compute currency conversions, times, and imperial weights, which caused a learning curve for the user as they had to adjust to the additional keys and calculations.

There was no need for separate actuating cranks or levers since speed was handled via direct key-driven action. Felt’s “Duplex Comptometer” of 1904 permitted keys in neighboring columns to be manipulated simultaneously rather than sequentially, allowing multi-digit figures to be entered in a single stroke using both hands’ fingers. In 1934, the Model K received a power-assisted mechanism with an electric motor drive (similar to an electric typewriter).

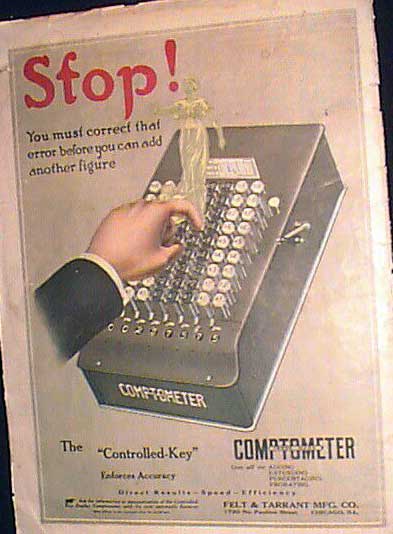

The mechanism’s core design addressed accuracy by preventing the recording of partial keystrokes. The 1913 Model E incorporated an advanced “Controlled Key” system that recognized such faults and locked the machine until they were rectified. Other possible mistakes were addressed when the Model H received a “start-from-clear” signal in 1920, and the Model M received leading-zero suppression in 1939. Almost one-quarter of the “Controlled-Key” Comptometer’s mechanism was dedicated to mistake prevention and repair.

The Comptometer’s keyboard is divided into columns, each displaying one place or power of ten in the input number. The keys in each column lower a lever that increases the length of the keyboard. The keys depress the lever by an amount proportional to their value. The nine key depresses the furthest, whereas the one key depresses the least. Springs attached to the lever pull it back up when the key is released. The column actuator, located at the free end of the lever, is a toothed rack that turns a pinion that drives an accumulator gear through a pawl and ratchet mechanism that stops the accumulator gear from spinning the lever’s downward stroke.

The accumulator gear only turns during the upward stroke of the lever. In addition, the accumulator gear turns a number wheel, which shows the accumulator’s stored value. A locking detent prevents the entire gear assembly from moving at inappropriate times.

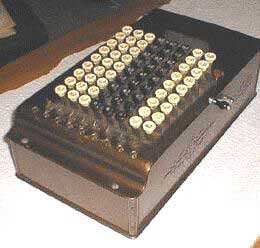

Comptometers were available in 8, 10, 12, and even 16-column versions as well as for British money (sterling), fractions, etc., on special order. The earliest and simplest Comptometer was produced from 1887 through 1903 and is wooden-cased (see the photo below). This earliest model had round key stems with springs between the keytops and the keyplate. The first examples had keytops of the “typewriter” variety with a metal ring surrounding a celluloid inset containing the character. Near the end of production, composition keytops were used. Some 6500 of the earlier wooden case models were sold over a sixteen-year period.

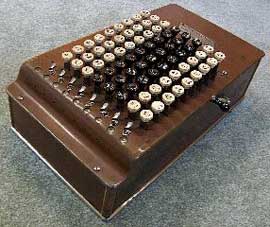

The A-model (see the photo below) was placed on the market in January 1904 and produced through September 1906. Some 2000-3000 A-model machines were produced during its lifespan. The “A” was the first of the steel case models which was to become the standard for the remainder for all “shoebox” models. The design was covered by Patent Nr 733379 and was a material factor in a later lawsuit with Burroughs. It is distinguished by the novel glass slab dial cover and elongated hanging decimal point indications. “Carry inhibitors” appeared as short protruding tabs for use during complementary subtraction.

With this model, the springloaded keys are replaced with flat stamped metal keystems. The spring mechanism was redesigned being located at the bottom of the keystems inside the case. A significant new feature dubbed duplex, allowed keys in different columns to be operated at the same time. This made multipiplying a practical operation for Comptometers since shipping and billing almost always involved some quantity times a unit weight or price. Felt’s genius is clearly at work here. Whereas the original model recorded the keypress on the downstroke, this model recorded on the upstroke! Beyond this, there were no safeguards and keys had to be given a full downstroke to prevent errors in operation, a very real concern that would not be addressed for another ten years.

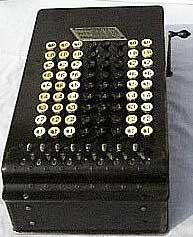

The B-model (see the nearby photo) was placed on the market in September, 1906, and introduced the “lazy-s” register cover, which was the final major case change for shoebox Comptometers. Just below the row of 1-keys were new small, shiney decimal pointers and “thumb-fitted” carry-inhibiters. These were important improvements, that improved operator efficiency.

Apparently some machines had a clean front panel while others carried 4 screws as needed by the A-model to hold the glass cover clamps. It provided no oil holes in the dial cover, but had two in the keyplate above the 9-row and one or two on the right side. The action of the canceling handle was particularly noisy and would produce a factory-like racket in offices when several were in operation simultaneously. It would seem that this model was produced only through May of 1909 when the next (C) model came on the market.

The C-model of Comptometer (so called “C-regular”) (see the nearby photo) started in 1909 and was followed 20 months later by the model “C-light”. Some minor mods were made, including the introduction of celluloid keys to replace the composition keys employed previously and a lighter key-depression. As with the B-models, a machine may or may not have carried those useless front panel screws. And for those fascinated by the history of oil holes, the C-light model sported some 29 of them in the dial cover and keyplate presumably in response to an almost complete lack in the prior model.

At first sight, the D-model (see the nearby photo) looks exactly like the F-model. But this is not true. The first visual clue is the missing “Controlled Key”, normally found next to the 9-key of the rightmost column. A second clue is that the D-model machine is almost 1 kg lighter than its F-model predecessor, each of its 8 columns having a quarter of a pound fewer parts. Both in cost of parts and assembly labor, it was surely cheaper to produce.

Since no more than 153 of this model were ever made, one could speculate on why it was produced at all. A reasonable theory is that (ignoring the ill-fated E-model) the “D” and the “F” machines were introduced simultaneously at different price levels, both somewhat higher than the C-model being replaced. For customers who felt the Controlled Key feature might not be worth the extra expense, the D-model was available, at least for a brief period. It was probably dropped from production due to a lack of demand as the Controlled Key was highly favored by the customers.

The arriving in 1913 E-model (see the photo below), was a short-lived model. While reportedly “on the market” from March of 1913 through May of 1915, the relatively small number of survivors would indicate that this model was less than a roaring success. It was introduced with one of the earliest color ads (see the lower image) and appeared on the back cover of the Aug 24, 1913 issue of Sunday Magazine of the Chicago Record-Herald. It seems that it proved too expensive and too tricky to manufacture, besides that field maintenance could have become a problem as the odd keytops may have broken more easily under heavy and constant use.

The F-model (see the nearby photo) arrived in May 1915. This machine was destined to bring volume production to the F&T factory. If machines were produced in strict sequence, sales of F-models would appear to have outpaced all previous models combined. It was in production through the end of the decade. A major feature was the presence of the “Controlled Key” (introduced on the ill-fated E-model) which locked the keyboard when any key was not fully depressed. Since these machines were operated very rapidly by trained operators, the ability to detect a partial stroke and the possibility for immediate correction without losing the running sum, they were warmly received. It may well have been the principal reason for the great popularity of this model over its lifespan.

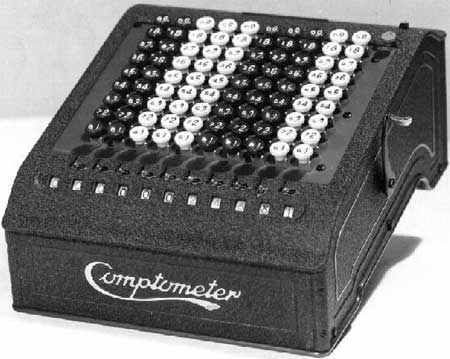

The H-model (see the nearby photo) appeared in 1920 as F&T’s first postwar model. It is easily distinguished from prior models by the presence of the Comptometer script logo on the front and back of the case. However, improved operational characteristics were to largely determine its fate in the marketplace. The forward placement of the clearing lever allowed the operator to zero the register with a single motion of the little finger, without altering her hand position over the keyboard. Internally, less obvious improvements included audible, tactile, and visual clear signals (bell, key pressure, and slight offset of register zeros).

All these refinements improved operator speed and accuracy but at some cost in the complexity of the mechanism, which required the front of the machine to be extended by about 1 cm. Support for this major step forward included one of the most detailed technical manuals for mechanical devices ever produced. The H-model was a big hit with users and justifiably so what with its many operational and aesthetic improvements. It was produced until 1926.

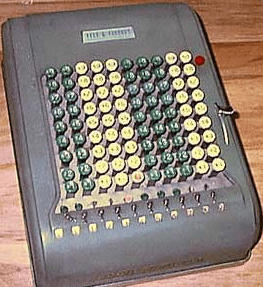

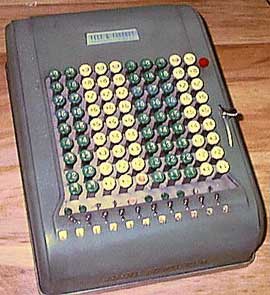

The final mass-produced machine of so-called ‘shoebox’ models was the long-lived “J” (see the nearby photo) that first appeared in February of 1926. Clearly intended to replace the H-model, it was set off visually from its predecessors by its green keys which replaced the traditional black. However, this distinction is not a reliable model indicator since keystems on F, H, and J models were identical and repairmen often simply replaced keys with what was in their bag.

Although the “J” had no major new features, many operational aspects were markedly improved and it received wide acceptance in the late “roaring 20s”. The model was in constant production until the start of WWII concurrently with the newer electric (K) and “streamlined” (M) models. Many of the survivor examples were still in operation at major US corporations until the late 1970s, a remarkable record spanning some fifty years of useful service.

The first change to the shape of the case came with the K-model (see the photo below) introduced in September of 1934. No doubt, a different shape was required to accommodate the changes to the mechanism needed for its electric design. Felt had resisted adding a motor-driven model during the 1920s and this late introduction had only modest success.

The Model ‘M’ (see the nearby photo) was introduced just before WWII and had a new style of case and the frames were redesigned accordingly. Early models had steel segment levers and numeral wheels with an actual zero embossed on the wheel. That is, they did not have any indication if a number existed to the left of the machine. The lack of indication of numbers to the left of a series of zeros evidently presented a problem and a hollow zero was introduced with a numeral wheel shutter. As soon as a column was operated all shutters to the right of the numeral dropped, giving a distinctive change of color in the open zeros.

Comptometer: Historical Significance

The Comptometer was a huge hit with businesses, particularly those with accounting departments, and it was extensively distributed. Large and costly, they were not meant to be used as personal calculators. When comptometer production peaked about 1970, they were replaced by computers rather than electronic calculators in the workplace.

Felt & Tarrant were the first to create a practical printing or recording calculator, marketed under the brand name “Comptograph” beginning in 1889. The Comptograph was never as successful as the later Burroughs adding and listing machine, and it was phased out in the 1920s. However, several of Felt’s Comptograph inventions were licensed to others (including Burroughs), becoming the foundation of the “accounting machine” business.

In December 1889, the first comptograph was sold to the Merchants & Manufacturers National Bank of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was the first time a recording-adding machine was sold. While still in business, the Felt and Tarrant Manufacturing Company produced both comptometers and comptographs. The Comptograph Company was founded in 1902 with the sole purpose of manufacturing comptographs. However, with the outbreak of World War I, the company was forced to close its doors. During the mid-1950s, the Comptometer Corporation resurrected the Comptograph brand for a new series of 10 key printing machines after 40 years. The front output display of Model A was made of polished glass. This model was manufactured between 1904 and 1906. It had a redesigned carry mechanism that decreased the power required to activate the keys to one-fourth of its predecessors. It also had the duplex capability, which enabled several keys to be pushed simultaneously. Finally, it had a streamlined clearing mechanism that took just one lever and one back-and-forth action to reset the machine. “The machine gun of the workplace,” as it was called in some World War I advertisements, was taking shape and developing the mechanism that would serve it for the next four decades.