The Past 100 Years of American Tariff Laws, and How Effective They Were

With tariffs dominating the news, you might be curious how the United States has used tariffs throughout history to create additional revenue, protect domestic industry, and negotiate with other global powers.

Better known as a duty or tax imposed by a government on imports and/or exports of goods, tariffs have been utilized by the United States far more than most people might think. In fact, the US has been using tariffs since 1789, when the country was still finding its way post-revolutionary war.

Today, we'll dive deeper into US tariff history, reviewing other times the US has used tariffs, why they were used, and how effective they were in meeting the intended goal.

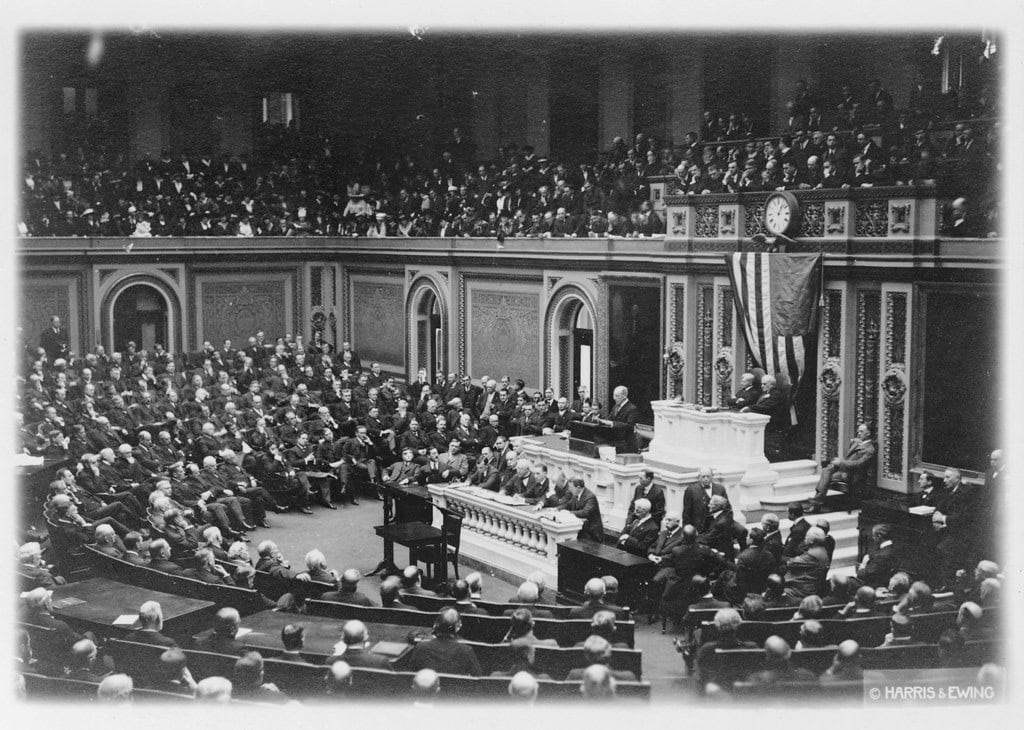

Revenue Act of 1913

Going back just over 100 years is a fantastic starting point. That's when the Revenue Act of 1913, was first signed into law on October 3rd by President Woodrow Wilson. Also known as the Tariff Act of 1913 or the Underwood Tariff, the most prominent act of this work was to re-establish the federal income tax in the United States and substantially lower tariff rates, giving the US authority to tax incomes “from whatever sources derived.” At the time, the income tax was small, just 1% on personal incomes over $3,000 for singles and $4,000 for married couples.

Switching gears to tariffs, this act in 1913 slashed tariffs across the board on any goods imported into the US by about 25%, on average. This sweeping legislative change undid multiple decades of protectionist US policy that protected American industry while adding to government revenue.

Tariffs were slashed because of this new federal income tax, which made up for any shortfall that would have occurred as a result of the decreased tariff. In the first year, the income tax only brought in $28 million, against $661 million that tariffs had brought in the previous year. However, this imbalance evened out as the tax rate increased, eventually rewiring the US economy.

Emergency Tariff of 1921

First passed under President Woodrow Wilson, the Emergency Tariff of 1921 was prompted by growing unrest in America, especially among farmers. President Warren G. Harding and Congress passed the tariff. At the very top of American economic concerns in the 1920s was the declining agricultural economy and its impact on farmers.

When Europe closed its markets with tariff barriers in 1919 after World War I, European markets saw a slowdown in demand for American farm products. As a result, this Emergency Tariff boosted farmers by raising duties on agricultural products like meat, corn, wheat, sugar, wool, and more.

Looking back throughout history, this tariff is now viewed as a knee-jerk reaction caused by the war’s end and Europe's desire to restore itself to a pre-war economy. While the US could flex some economic muscle, it was also the US's first flag around “unfair” trade policies, a term that is regularly used today. The tariff saved some but not all farms, especially those who worked with sugar and wool, but it didn’t have the overall impact Harding had hoped.

Fordney-McCumber Tariff

Another 1920s-era tariff designed to protect American factories and farms, the Fordney-McCumber Tariff, is named after two members of Congress. Unfortunately, it’s easy to call this a failure, as the tariffs imposed led to a loss of more than $300 million annually.

Congress hoped the passing of this tariff would come across as pro-business and promote foreign trade, but it eventually just led to France raising tariffs on automobiles from 45% to 100%. Spain raised tariffs on American goods by 40%, and Germany and Italy raised tariffs on wheat.

Unsurprisingly, the trade war that began with this tariff is now remembered poorly, especially when you realize that farmers in the country only saw their purchasing power go up as much as 3%. This wasn’t enough to counter the increased price of farm equipment, which directly led to the farmers' losses.

Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act

Better known as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, President Herbert Hoover signed the Tariff Act of 1930 into law on June 17, 1930. The act raised tariffs on more than 20,000 imported goods to shield American factories and industries from foreign competition while the Great Depression, which had started in October the previous year, was in its infancy.

Agriculture was hit especially hard, as the price of wheat, butter, and industry staples like steel rails increased significantly. The reality is that this act was little more than desperation to save a spiraling economy as farmers and businesses alike begged for economic relief. While this might have been an attempt to save jobs and boost prices, more than 1,000 economists at the time argued against it.

The result was that US imports dropped 66% from 1929 to 1933 and exports 61% during the same timeframe. Canada, Britain, and other economic allies all fought back, with Canada leading the way. Cutting American exports by 75% left broke farmers in even more desperate straits. Ultimately, this act did little more than make a bad situation worse.

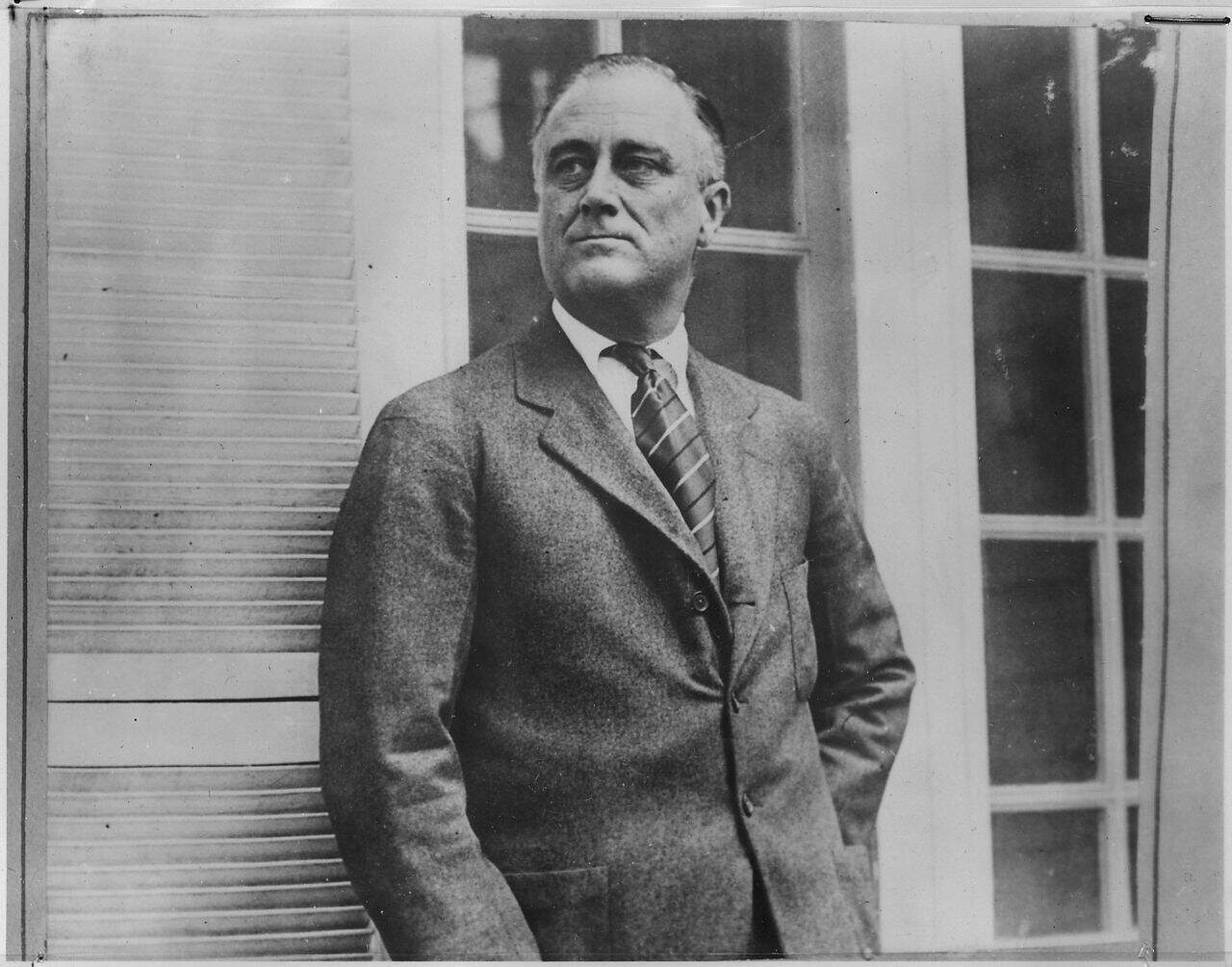

Reciprocal Tariff Act

Signed into law on June 12, 1934, the Reciprocal Tariff Act would give President Franklin Roosevelt the power to negotiate and enact reciprocal trade agreements with other nations, specifically Latin America. Positively, this act led to what is known as a more liberal trade policy that boosted the American economy through much of the 20th century.

It’s also easy to see this act as a response to the Smoot-Hawley Act, which was a disaster. While the previous act looked to boost America as a standalone entity, this reciprocal act indicated that the United States was ready to be a player on the global trade stage. By 1940, the US had 21 deals across Latin America, Canada, and Britain to cut tariffs on machinery, whiskey, and lumber.

The result is that US exports rebounded in a major way, increasing 60% between 1933 and 1937 as tariff rates dropped almost 50% during the same timeframe. This is now known as the birth of a more modern trade policy, as reciprocity became a staple in how the US became a global dealmaker in trade agreements.

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, signed on October 30, 1947, in Switzerland, was approved by 23 nations, including the United States. This policy remained in effect until the founding of the World Trade Organization in 1995, which speaks directly to its critical impact on trade for over 50 years.

The GATT, as it’s commonly known, looked to slash tariffs and boost global trade, but it wasn’t a law per se, just a framework that countries could use to negotiate lower duties. For the United States, in the first round of negotiations, it averaged a drop in duties from 25% to 19%.

Some like to think of this as the Reciprocal Tariff Act playing out on the global stage, which is a reasonably accurate description. Ultimately, this act led to what might be described as the “golden age by capitalism,” when GDP rose 4.1% in Europe annually and 2.5% in the US.

Trade Expansion Act

Enacted on October 11, 1962, the Trade Expansion Act gave the President of the US the power to negotiate tariff reductions of up to 80%. The specific target of this act was the European Economic Community EEC. It would lead to a tariff cut for over 6,300 items, all while giving financial assistance to any worker hurt by imported competition.

Looking back on this act, it was clearly a reflection of global times. The Cold War was in full swing, and the US wanted to counter the rising influence of Western Europe, including West Germany, as a trade bloc.

Kennedy knew he could boost US exports and hurt communism’s expansion at the same time. As a result, US exports jumped up $7 billion between 1962 and 1967, especially in manufacturing and farming. In addition, more than 50,000 farmers received aid by 1970.

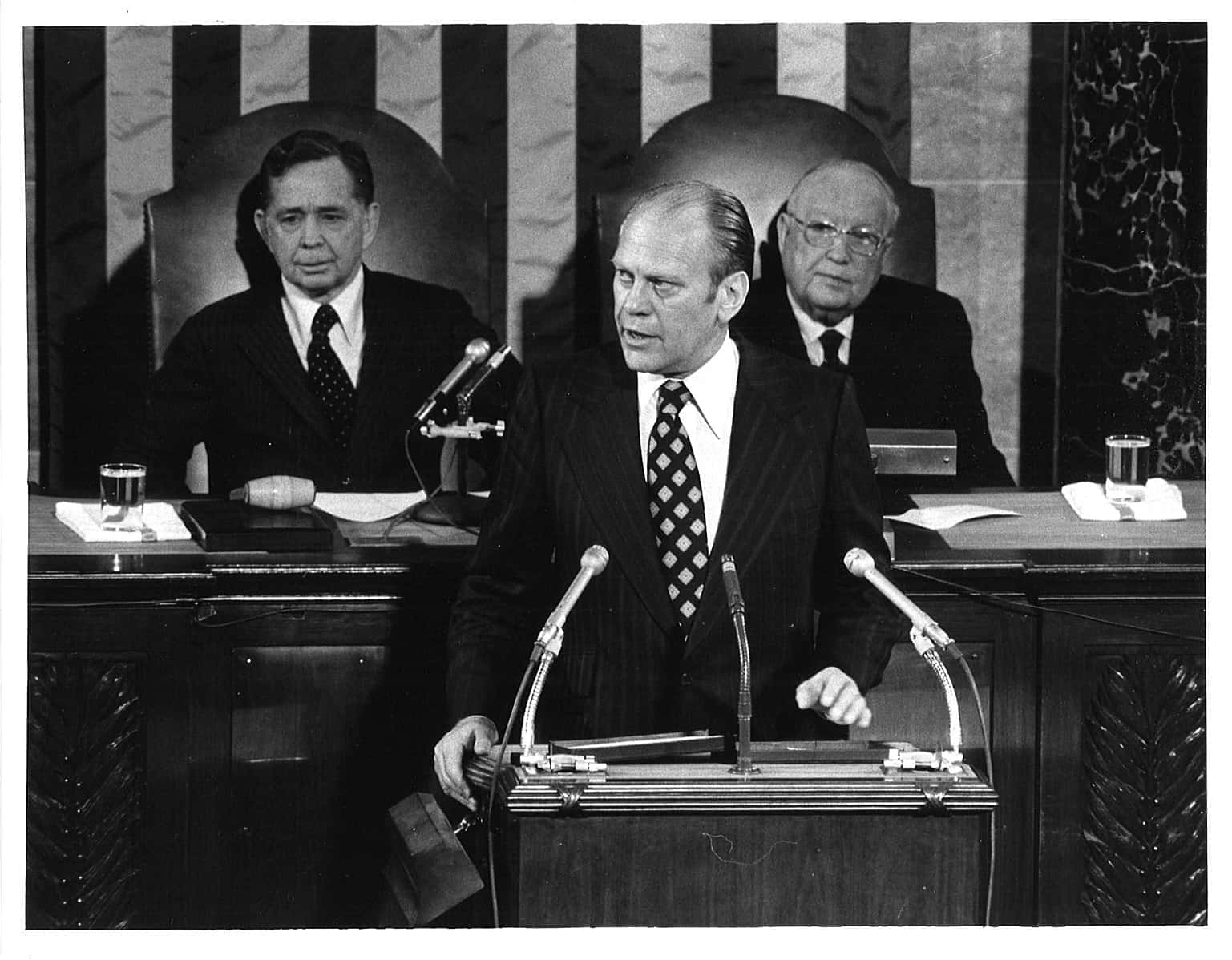

Trade Act of 1974

Essentially giving the power of the president to negotiate trade agreements that Congress could not amend or filibuster, this was a fast track to trade talks. President Gerald Ford signed this into law on January 3, 1975, and would greenlight tariff cuts of up to 60% in the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade), which targeted more than 8,000 goods.

The Trade Adjustment Assistance also received support in the form of more funding while allowing the US to retaliate against what it believed to be unfair trade practices. This was a US response to volatile oil pricing, Japan’s growing economy, and Europe showing more teeth. Ford bet that open markets were the best way to ensure America remained a global competitor.

Ford's first action, known as the “Tokyo Round,” cut global tariffs by 33%, with US rates falling from 8% to 5.6%. This mainly affected agricultural goods, chemicals, and machinery. In response, US exports also grew by a whopping 70% between 1974 and 1980, leading to more than $182 billion in revenue and giving the agricultural and aerospace industries a major economic boost.

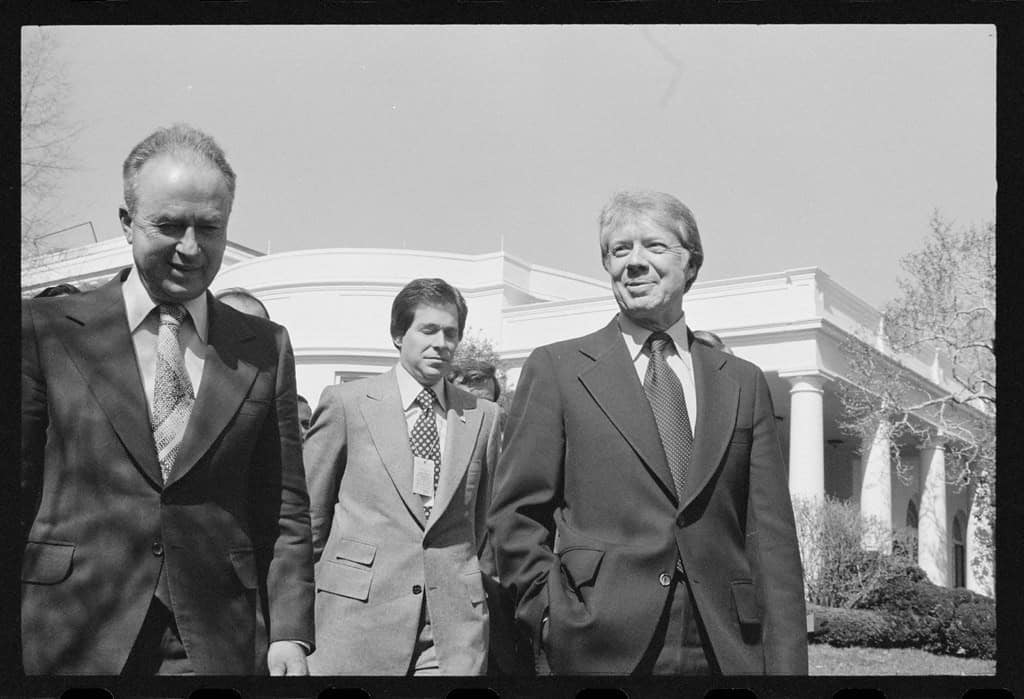

Trade Agreements Act of 1979

The Trade Agreements Act of 1979, signed by President Jimmy Carter in July 1979, implemented the 1974 act, which locked in US tariff cuts on thousands of goods, including electronics, machinery, and chemicals.

This act maintained the “fast-track” action for the president around global trade deals and is arguably the Tokyo Round’s finish line. As Japan and Europe were beating down US doors in various markets, this act was meant to help the US level the playing field. This allowed the US to grow the 1980 revenue of $182 billion to more than $228 billion just two years later. US exports also climbed by 25%, which economists view as a win.

Trade and Tariff Act of 1984

Enacted by President Ronald Reagan in 1984, this agreement primarily focused on creating bilateral trade authority for the US, Israel, and Canada. This act wasn’t necessarily focused on cutting tariffs but on giving the president the power to create tariff reductions through negotiating with other countries, which was essentially a tweak on the law President Ford signed in 1974.

This was an opportunity for Ronald Reagan to flex some global muscle to cut tariffs where it best served the American economy, but only with reciprocal tariffs. However, there was a “fast-track” tweak in this act that gave Congress back a little more power but left it short of being able to stop any deals the president was negotiating.

This bill created an opportunity to boost US exports to Israel, which doubled by 1990 while slashing 80% of tariffs on Canadian goods.

Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act

Another action by President Ronald Reagan was signed into law in 1988. This was an opportunity to weaken American trade policy. One primary focus of the law was to extend presidential fast-track authority for another five years, which gave way to NAFTA talks and boosted Section 301 from the 1974 act, which gave the US authority to call out unfair trade partners.

When this bill was signed, the US had a $152 billion trade deficit in 1987 as Japan was sending through car after car and electronics by the boatload, all while the dollar was weak. Ultimately, this bill was less about broader tariff cuts and more about protecting US industry against foreign markets.

Tariffs across North America were slashed, allowing US experts to Mexico to jump 50% in the next five years. Most importantly, the US trade deficit shrank to $66 billion by 1991, indicating that this act worked.

World Trade Organization

Headquartered in Switzerland, the World Trade Organization establishes, revises, and enforces rules regarding international trade by the United Nations. More than 166 countries participate, representing more than 98% of world trade.

The WTO oversees tariff cuts and seeks to settle any trade disputes through an intermediary policy that is a court-like system. The WTO isn’t just for show either as it has rules in place to stop trade wars. After its inception, global tariffs averaged 10% in 1995 to under 4% by 2015, and world trade tripled from $4.9 trillion to 17% trillion in 2019.

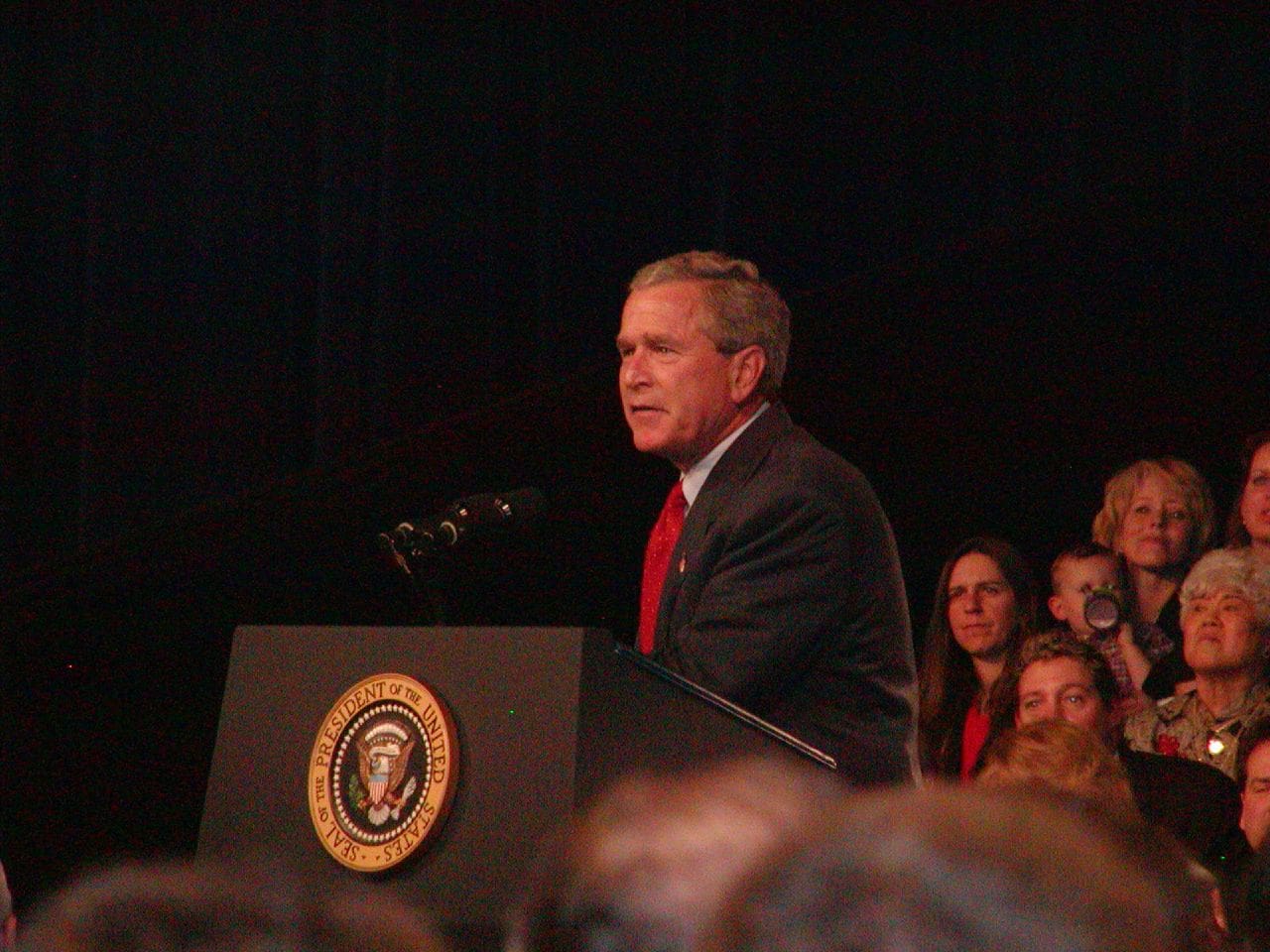

2002 United States Steel Tariff

On March 5, 2002, President George W. Bush enacted a trade tariff on imported steel, which began on March 20 and was lifted by December 4 of the following year. Tariffs on steel went from 8% to more than 30% across steel imports like bars, slabs, and flat-rolled steel due to more than 30 US steel firms going bankrupt since the late 1990s.

Many people view this as politics as usual with President Bush placating the rust belt that were swing states. Bush sold this as a lifeline to save jobs, but it resulted in global outrage as the EU complained and threatened retaliation, and the WTO ruled it illegal.

Ultimately, this just drove steel prices higher, which in turn led auto and appliance costs to rise and led to as many as 200,000 jobs in steel and steel-related industries to be lost.

Trade Act of 2002

Signed into law on August 6, 2002, the Trade Act of 2002 gave the President the authority to negotiate trade deals with other countries. This continued presidential fast-track authority through 2007 and only allowed Congress the power to approve or reject trade deals without any tweaking power.

President Bush was hoping to continue the idea that the US is a trade heavyweight. With China finally joining the WTO, he needed to continue looking at open markets to allow big US sectors like services, agriculture, and tech to continue growing. The result was free-trade agreements with Chile, Singapore, Australia, and CAFTA.

Chinese Tire Tariffs

In September 2009, President Barack Obama placed a 35% tariff on Chinese car and light truck tires under the Trade Act of 1974, which was triggered by a United Steelworkers petition. The goal was to stop cheap Chinese tire shipments from coming into the country, which had grown exponentially between 2004 and 2008.

As a result of this act, Chinese tire imports crashed by more than 67% in 2011, which meant just 15 million tires were coming into the US, leaving US producers to pick up the slack with 15% more output. It’s believed more than 1,200 jobs were saved, although China responded by placing tariffs on US chicken exports, costing more than $1 billion in sales.

First Trump Administration

In his first administration, Trump unleashed a blitz of tariffs beginning in 2018, with 25% on steel and 10% on aluminum imports. There were also smaller hits on solar panels, with 30%, and washing machines, though Canada and Mexico were able to dodge most of the tariffs as a result of the USMCA deal in 2018.

Much of Trump’s first administration can be chalked up to his “America First” language, which sought to reverse any idea around free trade and shrink the $621 billion trade deficit he inherited. The hope was that steel and aluminum tariffs would return jobs to the Rust Belt, and steel imports did fall by more than 27%, and US production rose by 6%.

Unfortunately, Trump’s actions cost Americans a lot. Steel prices spiked by 20%, costing as much as $50 billion more annually. There was only a 10,000-job gain in steel, which was overshadowed by more than 450,000 job losses in other sectors.

Second Trump Administration

The second Trump administration has seen a flurry of tariff activity, driving the average tariff to rise from 2% to more than 24%, the highest level in over a century. Trump’s “Liberation Day” executive order on April 2, 2005, imposed a minimum of 10% tariffs on all US imports while creating import tariffs on 57 nations ranging between 11% and 50% and caused a sell-off panic across the stock market.

These tariffs were expected to begin on April 9, but Trump shocked the world by suspending them at the last minute for 90 days for all countries except China. These tariffs, known as “reciprocal tariffs,” caused yet another worrying stock market crash and led to a flurry of media activity, labeling Trump’s tariff formula as impractical and not at all understandable by most global economists.

As it stands on April 9, only China has an elevated tariff in place due to the 90-day “Liberation Day” suspension.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©Petar Milošević / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license – License / Original