Born in 1847 in Springfield, Massachusetts, Gilbert Chapin received his education in common schools and even worked on a farm during his boyhood. Later, he made a name for himself as a banker and mathematician. In addition, Chapin was a true inventor at heart, with three patents for calculating machines to his name. His mathematical innovations led to the evaluation of smaller, pocket-size calculators later on. He also had patents for a bird-cage screen and a coupon cutter. Chapin also knew many languages, wrote four grammar books, and was a teacher at many boys’ schools. Later, Chapin wanted to be a minister and even got permission to preach.

Adding Machines of Gilbert Chapin

The American Gilbert W. Chapin (see biography of Gilbert W. Chapin) is a holder of three quite interesting patents for calculating machines — US patent №99533 and US patent №106999 from 1870, and US patent 646599 from 1900. He is a holder also of several other patents, e.g. for a bird-cage screen (US186711), for a coupon cutter (US454850), etc.

At this time, there were quite a few key-operated calculating machines, invented in Europe (see machines of Luigi Torchi and Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué). There are also a number of patents issued in the United States on machines of this class, such as the devices of Parmelee (1850), Hill (1857), Nutz (1858), and Winter (1859). The device of Chapin has better construction compared to all of them, although not resolving a common problem for the early key-driven calculators — overthrowing the numeral wheels under a quick keystroke.

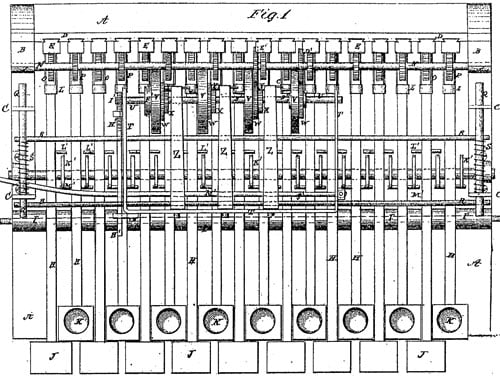

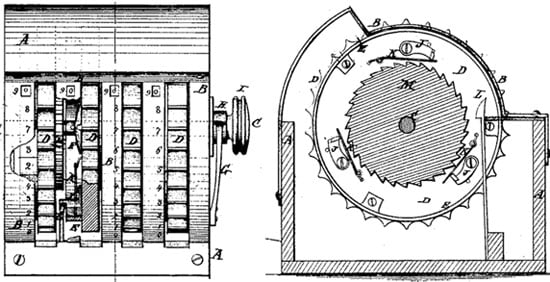

Let’s examine the first adding machine of Gilbert Chapin, using the patent drawings.

Chapin designed the machine so that it could add two columns of digits at once. It was also made to shift the accumulator mechanism and numeral wheels, so that it could add columns with four numbers.

The wheels don’t have numbers on them, but they’re still the number wheels of the machine. They can transfer the tens using a one-step ratchet device made of a spring frame and pawl (shown in Fig. 3). A pin in the lower wheel makes it work.

Figure 1 shows the units and tens wheels joined with their driving gears. These gears are not labeled but are connected to the shafts quickly (refer to Fig. 2). Next to the shaft, there are nine ratchet-toothed gears (marked ) and a similar group of gears attached to the shaft. Each ratchet-toothed gear works together with a ratchet-toothed rack. The rack is mounted at its lower end to a key lever, and a spring moves it forward to join with its ratchet gear.

There are two sets of key levers connected to a block. One set has finger-pieces and the other set does not. An elastic band at the back keeps them in place. Each set of racks has teeth numbered from one to nine. The first key only has one tooth, the second key has two teeth, and so on.

The inventor made a machine to add up numbers. It had wheels and a frame to shift them. The machine could add up units and tens, as well as hundreds and thousands. However, the inventor forgot to include a way to control how far the machine added numbers. This meant that even a small mistake could mess up the whole calculation.

Chapin’s machine, just like Parmelee’s and Hill’s machines, didn’t consider what would happen if a key was pressed too quickly. There was no way to control the wheels from flipping over.

Second Adding Machine of Chapin

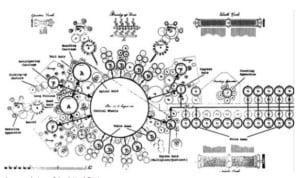

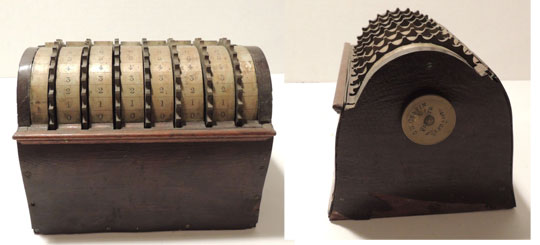

The second adding machine of Chapin (patented in September 1870) is a much smaller and simpler device (see the patent drawing below).

According to the specification, it has a simple, but reliable construction, missing the above-mentioned problem of the early key-driven calculators — overthrowing the numeral wheels under a quick keystroke.

It seems at least several devices of this type (see the upper photo) had been manufactured by Gilbert Chapin.

Calculating machines of this type will become quite popular at the end of the 19th/beginning of the 20th centuries (see for example the machine of Fossa-Mancini).

Third Adding Machine of Chapin

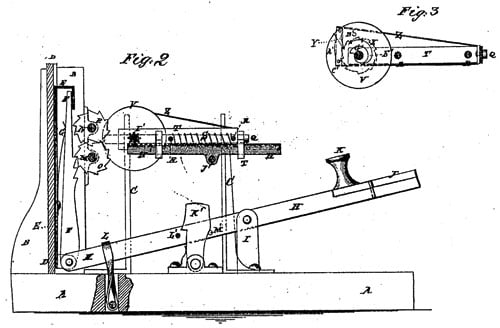

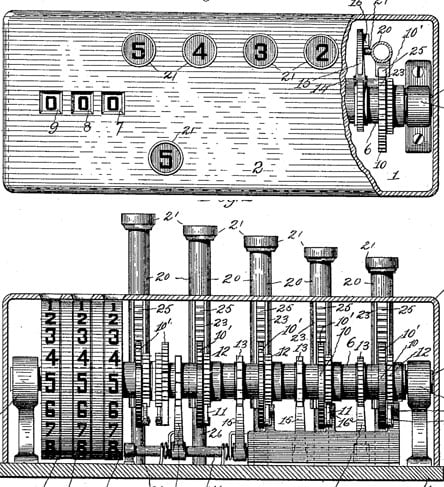

The third adding machine of Chapin, patented in April 1900, was again a key-operated adder, this time with a portable and reliable construction (see the patent drawing below). Unfortunately, despite its sound design, it remained unnoticed in the world of mechanical calculators.

The image featured at the top of this post is ©G-Stock Studio/Shutterstock.com.